Mystery disease is killing Caribbean corals

Biologists race to learn what it is and maybe how to thwart it

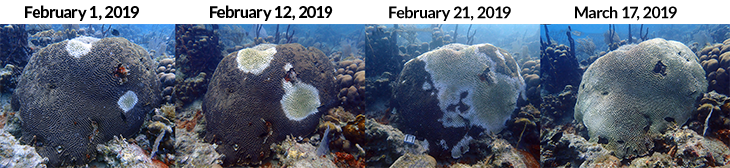

Maze corals on Flat Cay reef near St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Lesions expose the corals’ stark white skeleton. A deadly new disease is to blame — and it's spreading through the Caribbean.

M. Brandt

Last January, divers were studying Caribbean reefs off the U.S. Virgin Islands. Suddenly, they noticed something alarming on one reef. Lesions were eating into the colorful tissues of hundreds of corals. By the next day, some were dead. Only stark white skeletons remained. Others took two weeks to die. Within four months, more than half of the reef near the island of St. Thomas was dead.

The prime suspect is a disease first discovered off Florida in 2014. Known as stony coral tissue loss disease, scientists have nicknamed it “skittle-D” — like the candy. But skittle-D is far from sweet. It is responsible for one of the deadliest coral disease outbreaks on record.

Stony corals are the building blocks of reefs. Skittle-D is now ravaging one third of the Caribbean’s 65 stony coral species. Scientists don’t know if the infection is due to a virus, bacterium or some mix of microbes.

Whatever the cause, “it’s annihilating whole species,” says coral ecologist Marilyn Brandt. She works at the St. Thomas campus of the University of the Virgin Islands. There, she heads a science team investigating the outbreak from many angles.

Other coral diseases near St. Thomas have cut coral cover by up to half within a year, she notes. But this new epidemic has done the same damage in half that time. It is spreading faster and killing more corals than any past outbreaks here.

“It marches along the reef and rarely leaves corals behind,” Brandt says. “We’re pretty scared.”

A disease hot spot

Coral reefs cover less than 2 percent of the ocean floor. Still, they play an important role in ocean ecosystems. Reefs support about one-fourth of all marine species.

Sometimes mistaken for rocks or plants, corals are actually communities of tiny invertebrates. And they can get sick just like any other animal. Corals sometimes die from plagues. Other times, they can shake off milder illnesses, ones akin to the common cold.

The first coral disease was discovered in the Caribbean more than 40 years ago. Since then, dozens more have emerged around the world. And the Caribbean is now considered a coral-disease hot spot.

Biologists know little about these illnesses and how they work. Many marine microbes don’t grow well in the lab, Brandt explains. That makes studying coral diseases tough.

Even the names given to the diseases are vague. There’s dark-spot syndrome. And white plague. Names are based only on the visual cues to an infection. And it doesn’t help that many diseases look similar.

Florida scientists initially mistook skittle-D for white plague. Both infect stony corals. But scientists now know skittle-D is a new disease because it attacks stony coral species in a unique order. First hit are the brain corals. Then come the star corals and pillar corals.

Waters getting warmer

Climate change is providing an urgency to learn more about these diseases. Global warming is like a one-two punch for corals. Heat stress weakens coral defenses. At the same time, warming waters send microbes that cause disease into overdrive. Pollution, overfishing and other factors also can stress corals, making them even more vulnerable to disease.

“Coral reefs just can’t catch a break,” Brandt says. Facing one challenge after another, she says, “I feel like we’re playing whack-a-mole.”

Oceans are warming 40 percent faster than what United Nations scientists had predicted in 2014, finds a January 11 analysis in Science. That warming trend will likely continue as oceans continue to soak up roughly 93 percent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

As ocean temperatures rise, many corals have been hit by bleaching. This is where corals eject the symbiotic algae living inside the corals. Warming waters are also expected to make outbreaks of coral diseases more frequent and more severe. It’s something that researchers noted in a 2015 paper. And coral diseases will likely come to rival bleaching as a major source of coral declines.

Flat Cay reef off of St. Thomas, where Brandt’s team first noticed the skittle-D lesions, had been considered resilient. It rebounded from a major bleaching event in 2005 and from back-to-back hurricanes in 2017. But the new outbreak has killed all of the reef’s maze corals, a type of brain coral. And pillar corals could be next, Brandt says. Skittle-D “seems to be capable of changing the face of coral reefs as we know it.”

Performing reef triage

Brandt hopes to get ahead of the St. Thomas outbreak by using lessons learned from Florida. The skittle-D outbreak off the state’s southeast coast has persisted for five years. It now affects almost all of a 580-kilometer (360-mile) stretch of reef, including the Florida Keys, notes marine biologist Karen Neely. Such a lengthy assault surprised scientists. Coral disease outbreaks typically burn out after a few months.

Neely works at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. She and others are trying to save Florida’s stony corals by moving hundreds of healthy ones to tanks. There they can be studied, bred and protected from the outbreak. Meanwhile, divers have been slathering an antibiotic paste over sick corals still on the reef. Neely estimates that Florida researchers have treated nearly 1,200 colonies in the first half of 2019.

With the antibiotic, “we are seeing about 85 percent success,” Neely says. Though the paste seems to heal lesions, it doesn’t stop new ones from popping up. For now, she says, as treatments go, this paste “is the best we can hope for.”

The antibiotic’s success suggests the disease could be bacterial, Brandt says. But the disease might have viral origins. By that, she means, a viral disease might weaken corals so that a bacterial infection can step in. If true, the paste might be treating a symptom, not the cause.

Because the St. Thomas outbreak is just getting started, Brandt’s team is trying a different approach: removing sick corals and leaving the healthy ones behind. That could reduce the amount of pathogen in the water. In theory, that will make it more difficult for the disease to spread, she says. But her team won’t know if its strategy works until later this year.

Hunting a coral killer

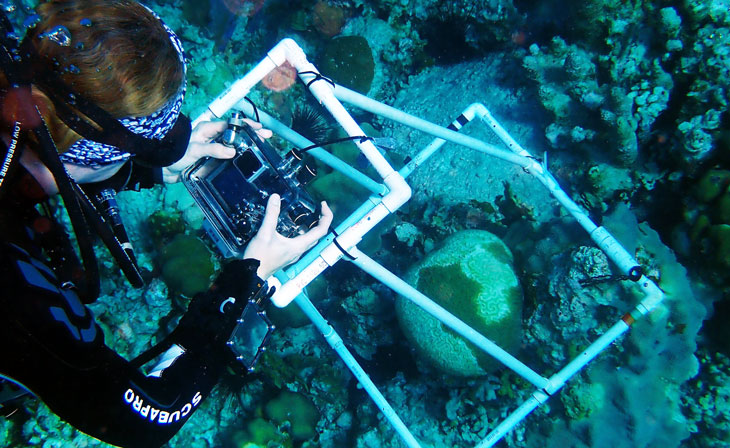

To find out what might cause skittle-D, Brandt’s team is looking at the microbes that live in and around corals. Building a list of suspects requires first sorting out what normally belongs on healthy corals.

Marine ecologist Amy Apprill works at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. She and others are studying microbes on sick corals. They are also looking at microbes living in sediments and the water swirling around St. Thomas’ reefs. Comparing those data with some from Florida corals may uncover similarities between the two outbreaks. That might help narrow the list of culprits, says Apprill.

The team is also focusing its microscopes on samples of brain and star corals taken just as lesions popped up. The corals came from a healthy reef in St. Thomas. They caught the disease during an experiment in which these specimens were placed near infected corals in an aquarium. “We might be getting a look at what ‘early’ disease looks like,” Apprill says.

She doesn’t expect to find just one pathogen. Many scientists think it may be groups of microbes that cause coral diseases like skittle-D.

More clues about skittle-D are coming from a research team led by Julie Meyer at the University of Florida in Gainesville. It found five types of bacteria dominate Florida corals infected with skittle-D. At least one type thrives in the low-oxygen conditions of dying tissue. And all these germs have been linked to outbreaks of coral disease elsewhere. The team shared its findings this past May on bioRxiv.

Profiling the victims

While some researchers hunt for suspects, Laura Mydlarz wants to know what happens to coral during an infection. A coral immunologist, she works on Brandt’s team. She is trying to figure out why some species of stony corals are more vulnerable than others are to diseases such as skittle-D.

Mydlarz’s lab is at the University of Texas at Arlington. There, her team has shown that the immune systems of corals that tend to die from infections work differently than do those in corals that typically survive.

Her team tricked corals into thinking sickening bacteria were infecting them. The immune systems of species that fought off the fake infection and lived went into a cell-recycling mode. Those that died instead had gotten stuck in a cell-death mode. Their cells died and were sloughed off. Her team reported its findings two years ago in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Mydlarz suspects something similar might happen in corals prone to skittle-D. That’s because the species in her study that favored cell-death mode are among those hit hardest by the new outbreak.

A disease on the move

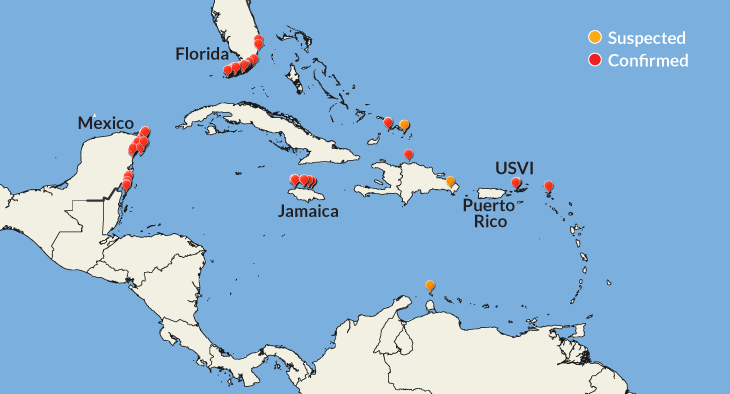

Researchers are trying to keep up with skittle-D’s spread. Germs may have traveled from Florida to St. Thomas in the ballast water of ships, says Dan Holstein. He’s a coral reef ecologist. Skittle-D also has shown up in reefs off Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and other Caribbean islands.

Holstein is a member of Brandt’s team who works at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. He has been looking at ocean currents and other factors in hopes that he might be able to forecast where skittle-D will show up next. The team’s early results point to Puerto Rico.

In May, divers confirmed that the ongoing outbreak is inching toward the Puerto Rican island of Vieques. Star corals about 17 kilometers (11 miles) offshore and 40 meters (130 feet) deep are already pocked with lesions, notes Tyler Smith. He oversees the reef-monitoring program at the University of the Virgin Islands in St. Thomas.

The discovery was disheartening, Smith says. Scientists knew that star corals in shallower waters were at risk. They had hoped those living in deeper waters might be spared. He likens the deep reefs to a powder keg. They are made up of hundreds of millions of densely packed colonies where disease can jump easily from coral to coral. If skittle-D hits them, “the spread of [the disease] might pick up very rapidly,” Smith says, “even more than it is now.”

Brandt’s group continues to monitor reefs in the U.S. Virgin Islands. A June survey of 270 sites around St. Croix spotted new coral infections. “It was a moment of panic,” Brandt says. In the end, it turned out these corals had the less-severe white plague. None had skittle-D. That, she says, offers a glimmer of hope — at least for now.