New ultrathin materials can pull climate-warming CO2 from the air

Called MXenes, these nanomaterials show promise for slowing the rate of climate change

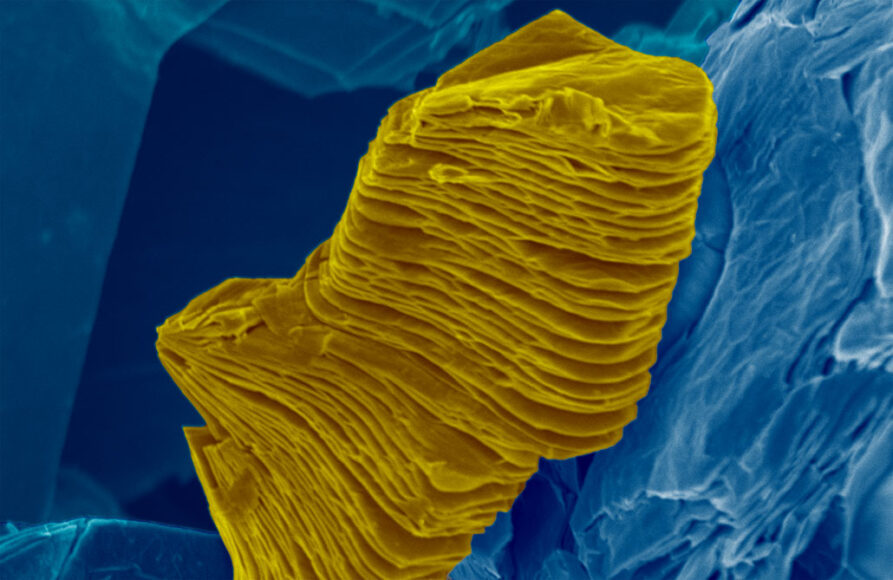

This is a false-color scanning electron micrograph of a MXene particle, which consists of many individual sheets loosely bound together in a stack.

Ahmed Majed and Karamullah Eisawi/Tulane Univ.

By Shi En Kim

This is another in our series of stories identifying new technologies and actions that can slow climate change, reduce its impacts or help communities cope with a rapidly changing world.

One up-and-coming class of tiny materials could help solve the huge problem of climate change. How? By catching climate-warming carbon dioxide out of the air.

The nano-scale materials are called MXenes (MAX-eenz). Their name comes from their structure, which is made up of alternating layers of M and X atoms. “M” layers consist of some transition metal. (Those atoms are bulky and can shed a variable number of electrons.) “X” layers contain atoms of another element, such as carbon or nitrogen.

A single MXene sheet contains a few of these alternating M and X layers chemically bound to each other. It may look like MXM or MXMXM. Each sheet is typically only about 1 nanometer thick. For comparison, a sheet of paper is 100,000 times thicker.

MXenes normally come as stacks of these individual sheets. The many separate sheets inside a stack add up to a huge overall surface area. It’s like how the combined surface area of all the pages in a book is much larger than that of just the covers.

In fact, the total surface area contained in one gram (1/400 ounce) of MXene “can cover a football field,” notes Per Persson. He’s a materials scientist at Linköping University in Sweden.

Atoms across MXenes’ large surface areas can interact with their environment. That includes grabbing carbon dioxide, or CO2, out of the air around them — a process called carbon capture.

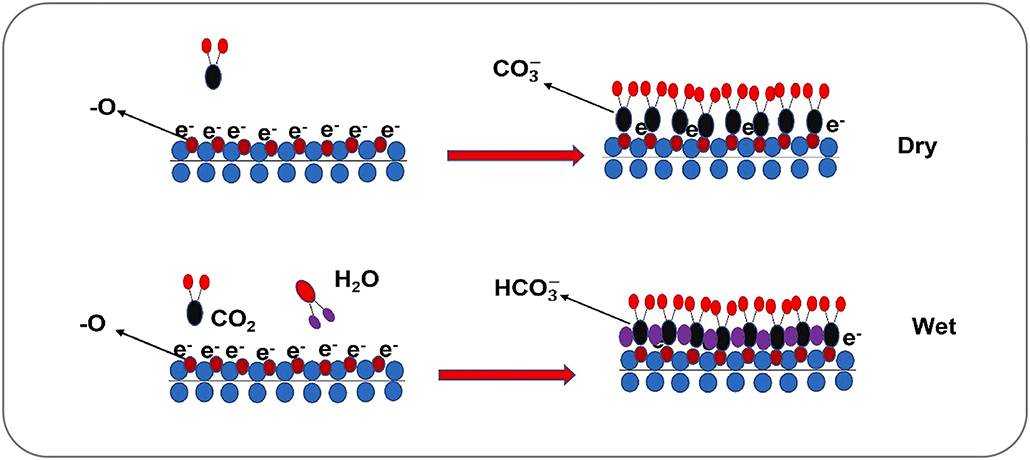

MXenes are excellent at snagging CO2, Persson says. Some researchers think it’s because CO2 molecules are just the right size to fit between a MXene’s tight layers. Persson suspects it’s because CO2 and MXenes like to share electrons, allowing CO2 to chemically stick to a MXene’s surface.

What’s more, MXenes chemically ignore other common gases — such as nitrogen, the most abundant gas in Earth’s atmosphere. This could allow MXenes to suck climate-warming CO2 out of the air while leaving the rest of the atmosphere alone.

Several research groups have been exploring MXenes’ potential to capture CO2 from the air. In the Linköping experiments, “CO2 stuck to the MXene surface like refrigerator magnets,” Persson says. “It was absolutely amazing.” His group has shown that MXenes can sponge up as much as half their weight in CO2.

One large family

MXenes don’t exist in nature. Scientists have to make them.

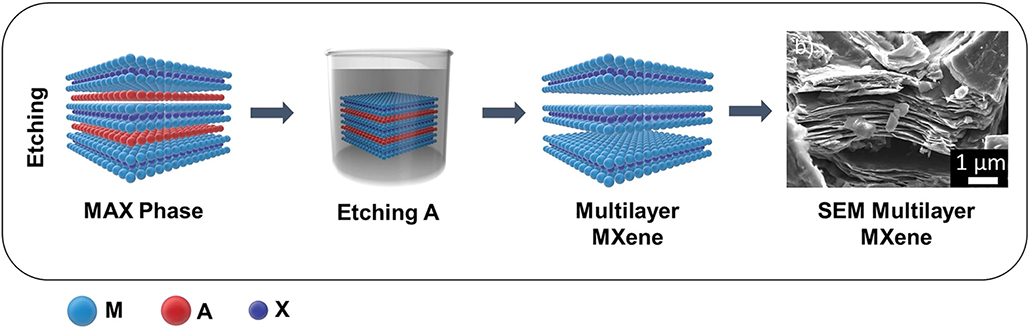

They do this using other labmade compounds called MAX phases. Like MXenes, MAX phases are layered crystals. But MAX phases have extra sheets of metal “A” that sandwich between their M and X layers.

To turn MAX phases into MXenes, scientists must eat away the A layers using a strong acid. A common one is hydrofluoric (Hy-droh-FLOOR-ik) acid. (This acid is so harsh that it can dissolve the minerals in your bones!) The treatment leaves behind just the M and X layers.

Since the materials’ discovery, scientists have found safer ways to make MXenes. These techniques use milder acids or bases. One such chemical is sodium hydroxide. That’s an ingredient in soap. Another recent method is to use molten fluoride salts to etch away the A layer in MAX phases. No harsh compounds are needed there, although it does take high temps — up to 750° Celsius (1,380° Fahrenheit).

MXenes are the largest group of flat, sheetlike nanomaterials. Scientists refer to them as being largely two-dimensional, or 2-D. Another famous example of a 2-D material is graphene.

MXenes have “probably the largest diversity and tunability any 2-D material can offer,” says Michael Naguib. By tunable, this engineering physicist means that MXenes can be tweaked to take on different properties. Naguib works at Tulane University in New Orleans, La. He made the world’s first MXene in 2011, a titanium carbide.

Scientists have now made more than 50 MXenes. New ones arise when scientists mix and match different M and X atoms. Each MXene has slightly different properties, from how well it conducts electricity to how strong it is.

Scientists can even modify existing MXenes by treating them with different chemicals. This involves covering the MXene’s surface with new atoms, such as oxygen and fluorine, to change its behavior. For more than a decade, scientists have been tailoring different MXenes for use in batteries and other energy storage devices. But tweaking MXenes’ chemistry can also alter their ability to collect CO2.

In an October 4 paper in Chem, engineers at the University of California, Riverside, reviewed the potential widespread use of MXenes. In a statement, lead author Mihri Ozkan noted, “Their unique properties make them excellent candidates for capturing CO2.”

Painting on a CO2-absorber

Freshly prepared MXenes appear as a dark-colored powder. Each fleck contains many MXene sheets. Under a microscope, they look like loose sheets of paper. MXenes become easier to work with when scientists add this powder to water, creating an ink, says Anupma Thakur. She’s a materials scientist that Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind.

As ink, Thakur adds, scientists can simply paint MXenes onto desired surfaces, such as fabric, plastic or glass. Or, if a thick enough coat of MXene paint is peeled carefully off a surface, it can even become a free-standing sheet.

When toughened with polymers, MXene films can durably separate CO2 from exhaust gas. For carbon capture, Persson imagines fitting MXene filters atop chimneys where the exhaust from burned materials is rich in CO2.

To absorb CO2 from the air elsewhere, Thakur suggests putting stacks of MXene screens out in the open. This method would be less efficient at capturing CO2, though, since average levels of CO2 in the air far from pollution sources are quite low.

Keep in mind, trapping CO2 anywhere is just a first step in managing this pollutant, says Vitalie Stavila. He’s a materials chemist at Sandia National Laboratories in Livermore, Calif. “The problem is, what are you going to do with all that CO2?” he says. Scientists will have to figure out how to retrieve the trapped gas from the MXenes after they’re full.

MXenes could be heated up to release their CO2 for long-term storage somewhere else. Flushing MXenes with a different kind of gas, such as hydrogen, might also remove the CO2 from them. Then the MXenes could be reused for a new round of carbon capture.

MXenes could also help transform the CO2 they capture into other useful compounds, Stavila says. That’s because MXenes are catalytic. That means they can help drive other chemicals, such as CO2, to react. MXenes also conduct electricity. Since they like sharing electrons with CO2, they can ferry those electrons to other compounds.

As a result, “you can do [transformations of CO2] that may not be otherwise possible,” Stavila says. For instance, with a boost from MXenes, CO2 can react with hydrogen to form methanol or formic acid. These liquids can be used as fuels to reduce people’s reliance on newly mined fossil fuels, which add new CO2 to the atmosphere. Or, better yet, these liquids can be stored somewhere to keep their carbon out of the air for good.

Challenges ahead

Since they’re still fairly new, MXenes today are only used in research. Scientists have to iron out some kinks before these will be ready for use in the real world. And that will take several years, at least.

One weakness of MXenes is that they can break down and transform into other solids called oxides in the presence of oxygen. So water and oxygen make MXenes less reactive. But scientists think they can overcome this problem by tweaking MXenes’ structure. Capping the materials’ edges with bulky salts, for instance, could shield MXenes from damage by oxygen.

It’s also hard, right now, to make large amounts of MXenes. In the lab, researchers can make only several kilograms (pounds) in a single batch. Several companies are working out how to boost batch sizes.

But Thakur points out one irony: Making MXenes for carbon capture can have a big carbon footprint. It takes a lot of electricity to get the heat needed to make them, she notes. Much of that electricity is made using CO2-spewing fossil fuels. It’s important to make sure that the energy used to make these materials doesn’t spew more CO2 than the MXenes can later sop up. Otherwise, that would defeat their use in carbon capture.

MXenes also cost a lot to make. The high cost of making these materials would be less important if they could withstand thousands of CO2 capture-and-release cycles. That way, scientists wouldn’t have to keep making new MXenes.

So far, no one has tested MXenes’ durability for stored CO2 removal and reuse. Still, it helps that MXenes are mechanically rugged. Research has shown that certain types can be as strong as steel.

The Riverside group’s new paper also points to a related family of nanosheets that may prove good CO2 sponges. Made from MXenes, they’re known as MBenes, because the “X” layer is made up of boron atoms. These materials are harder to make than MXenes. So most research on them has been done with math or computer models. But MBenes could have unique mechanical and electrical traits, Ozkan’s team finds. And those just might help them last through many, many cycles of CO2 capture and release.

Each year, human activities spew tens of billions of tons of CO2 into the air. That’s equivalent to the weight of tens of billions of elephants. Carbon absorbers, including MXenes or MBenes, can’t catch it all. As such, they’re never going to replace the need for reducing emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

Still, given the urgency of climate change, even a quick or partial fix — such as carbon capture — can’t be ignored. “At this point in time,” says Persson, “we need to look at all the possible solutions.” And MXene-like materials are emerging as potentially important candidates.