Ingenuity helicopter makes history by flying on Mars

The flight in the Red Planet’s thin air is the first in a planned series of daring flights

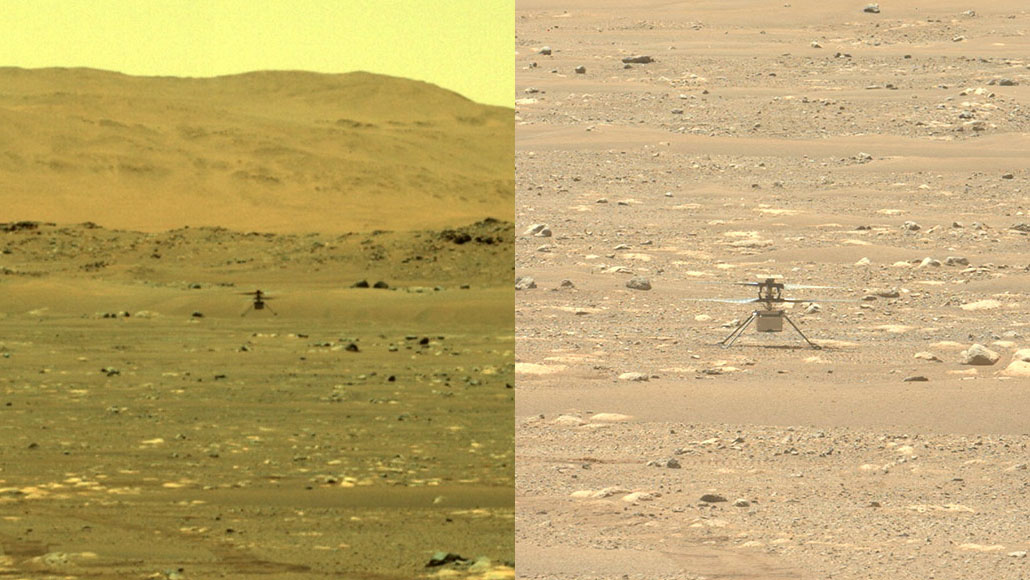

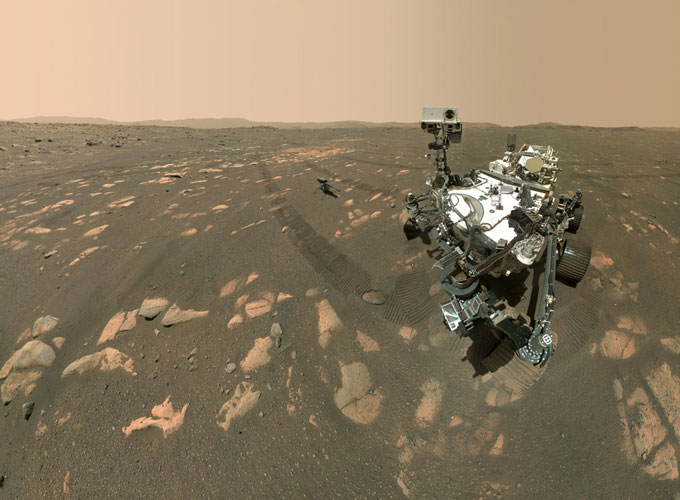

The Mars rover Perseverance captured these images of Ingenuity as the helicopter hovered above the Red Planet’s surface (left) and after it successfully landed (right).

JPL-Caltech/NASA

NASA has just flown a helicopter on Mars. Named Ingenuity, the craft hovered for about 40 seconds above the Red Planet’s surface. This marks the first flight of a spacecraft on a planet other than Earth.

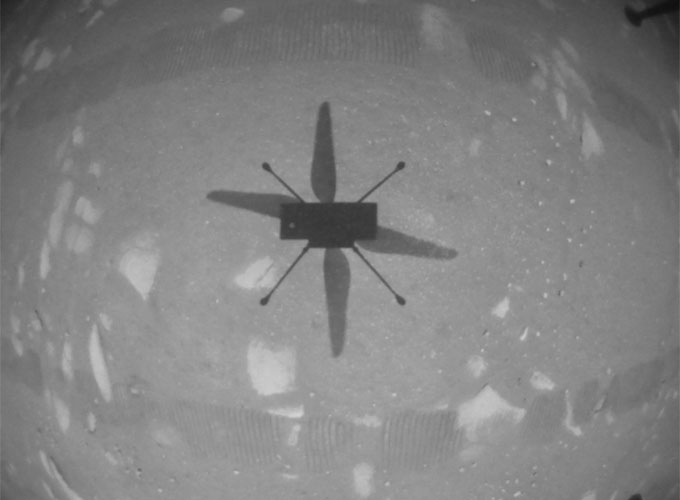

In the wee hours on April 19, the helicopter spun its rotor blades and ascended into the thin Martian air. It rose about three meters (or 10 feet) above the ground. After pivoting to look at NASA’s Perseverance rover and snap a picture of its own shadow, the small copter settled back down to the ground.

“Goosebumps. It looks just the way we had tested it,” said MiMi Aung in a news briefing after the flight. Aung is Ingenuity’s project manager. When this engineer saw the copter’s test trial on Mars, she described it as an “absolutely beautiful flight. I don’t think I can ever stop watching it over and over again.”

At about 6:35 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) on April 19, a hush fell over Ingenuity’s mission control room. Data from the flight were just starting to arrive here at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, Calif. Håvard Grip is Ingenuity’s chief pilot. In short order he announced: “Confirmed that Ingenuity has performed its first flight — the first flight of a powered aircraft on another planet.”

At once, cheers erupted throughout the room.

“It’s amazing, brilliant. Everyone is super excited,” said Taryn Bailey. “I would say it’s a success.” Bailey is a mechanical engineer and team member.

The flight had been delayed for a little more than a week when a test of the rotor blades showed problems. The engineers updated the aircraft’s software. The flight was back on.

Following Ingenuity’s brief time aloft, Aung congratulated her team. “Take that moment [to celebrate],” she told them. Then, she added, “Let’s get back to work and more flights.”

Testing now, science later

This first-ever flight was a test of the technology. It’s adding “a tool we haven’t been able to use,” said Thomas Zurbuchen. He’s NASA’s associate administrator for its science missions division. Now that NASA knows the helicopter works, he added, this tool will be “available for all of our missions at Mars.”

Ingenuity’s mission is set to last 30 Martian days. (That’s equals some 31 Earth days.) During that time, it won’t, in fact, do any science. But its success proves that powered flight is possible in Mars’ thin atmosphere. Future aerial vehicles on the Red Planet could help rovers or human astronauts scout safe paths through unfamiliar landscapes. Or a copter might survey tricky terrain that a rover can’t traverse.

When NASA first began testing early prototypes of a Mars helicopter at JPL in 2014, it wasn’t clear that flying on Mars would even be possible, Aung said. “It’s challenging for many different reasons.”

Though Mars’ gravity is about one-third that on Earth, the density of the air on Mars is only about a hundredth that at sea level on our planet. It’s difficult for a helicopter’s blades to push against such thin air hard and still get off the ground.

Amelia Quon is an Ingenuity engineer at JPL. At a news briefing on April 9, she recalled that some people had “doubted we could generate enough lift to fly in that thin Martian atmosphere.” So for five years, she and her team put prototypes — and ultimately Ingenuity itself — through a battery of tests.

Explains Quon, “My job … was to make Mars on Earth, and enough of it that we could actually fly our helicopter in it.” Her team’s Mars simulation chamber could be emptied of Earth’s air and pumped full of carbon dioxide at Mars-like densities. Some versions of the helicopter were suspended from the ceiling to simulate Mars’ lower gravity. Wind speeds up to 30 meters per second (67 miles per hour) were simulated with a bank of about 900 computer fans blowing at the helicopter.

The final design called for a light craft; it weighs a mere 1.8 kilograms (4 pounds) on Earth. (It’s mass will be same on Mars, although its weight isn’t.) Its wingspan runs roughly 1.2 meters (3.9 feet). Those rotors are longer than what a similar vehicle would need to fly on Earth. They rotate faster, too — some 2,400 times a minute. By the time Ingenuity hitched a ride to Mars on the Perseverance rover in July 2020, the engineers were confident the helicopter could fly on Mars.

The rover’s role

Perseverance landed at a site called Jezero crater on February 18. Folded up and covered by a protective shield beneath the rover’s belly was Ingenuity.

Over the next few weeks, Perseverance motored in search of a flat spot for the whirlybird to launch. It found one, and Ingenuity slowly unfolded itself and was lowered gently to the ground on April 3. The rover then drove away quickly to get Ingenuity out of its shadow. A solar panel could now charge the helicopter’s batteries enough to make it through the freezing Martian nights.

On April 8 and 9, Ingenuity unfolded its rotor blades and tested their ability to spin. After trouble-shooting the software problem and retesting the rotor blades on April 16, NASA gave a green light to fly at roughly 3:30 a.m. EDT on April 19. That’s about 12:30 p.m. Mars time. Such an early-afternoon liftoff would give the craft’s solar panel enough time to charge up its batteries for the flight. Perseverance’s weather sensors also suggested that the winds would be only about six meters per second (13 miles per hour).

Ingenuity had to pilot itself. Mars is far enough from Earth that light signals take about 15 minutes to travel between the two planets. For that reason, NASA engineers could not manage second-to-second steering challenges. And Mars’ thin air makes the helicopter difficult to steer. “Things happen too quickly for a human pilot to react to it,” Quon notes.

Perseverance filmed the flight from about 65 meters (almost 215 feet) away. Ingenuity also filmed its flight using two sets of cameras. Downward facing navigation cameras captured the view below it in black and white as color cameras scanned the horizon.

Now that this first flight went well, NASA engineers hope to set up as many as four more flights, possibly starting as soon as April 22. Each will be a little bit more daring — and risky, Aung says. “We are going to continually push all the way to the limit of this rotorcraft.” And each flight will be a nail-biter. Just one bad landing could end things as Ingenuity has no way to right itself after a fall.

In fact, that may be the way the mission ends. “Ultimately, we expect the helicopter will meet its limit,” Aung admitted at an April 19 news briefing. Even if it wipes out in a crash, her engineering team will have learned valuable lessons.

Eventually, Perseverance will drive off, leaving behind the little helicopter that could. The rover will soldier on to continue its own mission: to search for signs of past life in Jezero crater, and to store rocks for a future trip to Earth.