The next astronauts to walk the moon will be more diverse than the last

Future Artemis crews are expected to include women and people of color

NASA’s Artemis program is expected to send the first woman and first person of color to the moon.

JANIECBROS/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Fifty years have passed since the last astronauts walked on the moon. With the November 16, 2022, launch of Artemis I, NASA is finally preparing to send people back. This generation of spacefarers will face new challenges. NASA expects them to stay on the moon longer and learn how to live there. Their work will pave the way to send the first people to Mars.

NASA’s Apollo missions in the 1960s and 1970s sent 24 white men to the moon. Today’s mission goals will require 21st century astronauts to bring different knowledge, skills and temperaments than Apollo crews did. Fortunately, NASA is now picking from a much wider array of candidates.

Thanks to social, political and scientific changes over the last half century, the sex, race and fields of expertise of today’s astronauts are more diverse. NASA has declared that upcoming moon missions will include the first woman and the first person of color. Some groups are even thinking about how to include people with disabilities in spacefaring.

This progress doesn’t just broaden the pool of talent available for creating a more permanent human presence in space. Future lunar crews also may reflect our lives on Earth more faithfully, making space for everyone.

Meet the modern astronauts

NASA has not yet selected the next visitors to the moon. But there are only about 50 people to choose from. That includes 43 active astronauts and 10 candidates still in training. The members of that cohort come from a variety of backgrounds. The list includes medical doctors and military pilots. It also includes geologists, microbiologists, engineers and others. Of NASA’s active astronauts, roughly one-third (37 percent) are women.

“The astronaut corps is, of course, NASA’s most visible workforce,” says Lori Garver. She was NASA’s deputy administrator from 2009 to 2013. “Because of that, NASA has, I think, a responsibility to have an astronaut corps that reflects the nation.”

Modern astronauts already differ from those in Apollo missions. For its first class of astronauts in 1959, NASA recruited only military fighter pilots. And they all had to be shorter than 5 feet, 11 inches to fit inside NASA’s space capsule. At the time, all military test pilots were white men — so, all astronauts were too.

NASA recruited its first class of “scientist-astronauts” in 1964. That move drew criticism from pilots. One naysayer was Eugene Cernan, who went to the moon on the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. In an interview, Cernan called science “a parasite” on the moon program. “Science is not the reason we learned to fly,” he griped. Cernan later referred to his Apollo 17 crewmate Harrison Schmitt, a geologist, as “Dr. Rock.” And Cernan said he wasn’t sure if Schmitt would be able to get out of a tough spot on his own.

But according to NASA’s mission report, Apollo 17 was “the most productive and trouble-free manned mission.” It “demonstrated the practicality of training scientists to become qualified astronauts.” Today, 42 percent of NASA’s active astronauts have training in science or medicine. Their fields range from oceanography to physics.

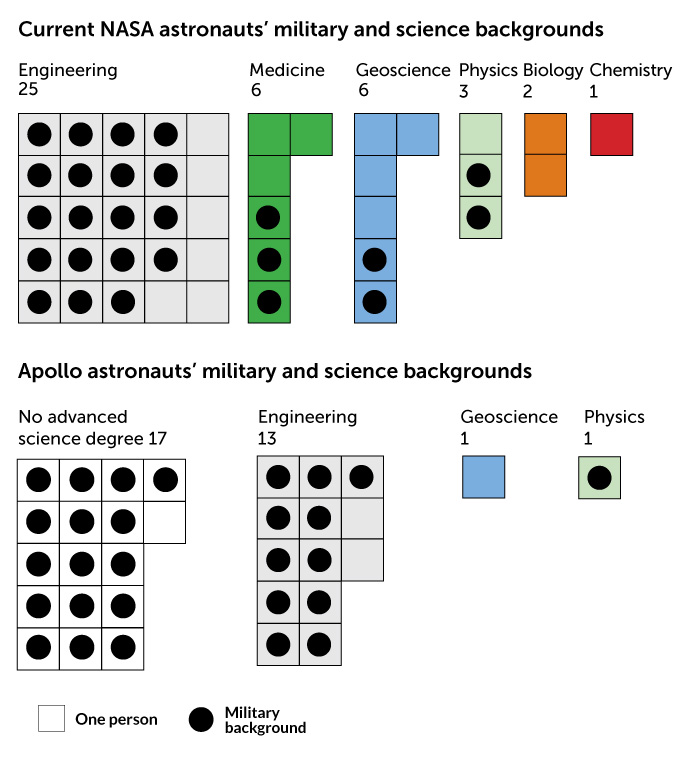

Science expertise

A science background is considered a necessity for today’s 43 active astronauts (top). Many astronauts are in the military. But they also have degrees in medicine, geoscience or physics. The original Apollo astronauts (bottom) were mostly military pilots. Only some had engineering backgrounds.

What makes an astronaut

NASA’s definition of astronaut doesn’t actually require going to space. Once you’ve made it through the application and training process, you’re a member of the astronaut corps. That’s true whether you leave Earth or not.

The first step in applying is “underwhelming,” says Zena Cardman. This geobiologist joined the astronaut corps in 2017. She has not yet been to space. “You submit a very short resume,” she says. “Then you wait for a long time” for a response.

There are a few basic requirements to apply. You must be a U.S. citizen. You also need a master’s degree in science, engineering or math — plus two years of work experience. Pilots can swap out the two years of work experience with 1,000 hours of jet-flying time. Candidates who make it through that first round travel to Houston for a two-round interview process.

Astronaut Reid Wiseman offered more details in an August news briefing. Wiseman is the chief of NASA’s Astronaut Office in Houston, Texas. “What we’re looking for in these first few Artemis missions … first and foremost, is technical expertise,” he said. A lot of those desired skills revolve around acquiring resources to support long stays on the moon.

Artemis III plans to send people to the lunar south pole as soon as 2025. That could be a good place to put a long-term base. The south pole has regions that will be in sunlight for the entire 6.5-day Artemis III mission. The light will help generate energy from solar power. The lunar south pole also has regions in permanent shadow. Those pockets hold water ice that future human settlements could use for water and fuel.

The goal of finding and using resources on the moon is part of why science backgrounds — especially in geology — have gained importance for astronauts. But in the astronaut corps, everyone does everything, Cardman says. Her background is in geology and microbiology. But she’s getting trained in engineering and aviation. Her test-pilot colleagues, meanwhile, are learning geoscience.

Beyond technical skill, Wiseman says, the next most important quality NASA looks for is: “Are you a team player?” Working together was important on the Apollo missions. But those missions lasted 12 days at most. Only three days at most were spent on the lunar surface. Astronauts on a weeks-long Artemis mission to the moon or a years-long mission to Mars will need to survive in stressful, isolated environments. Getting along will be crucial for them to stay alive.

That’s why the interview process includes teamwork exercises, Cardman says. Those activities mimic the kinds of situations in which astronauts might find themselves.

The interview also involves medical screening. The details are not public. But “they really go quite in depth,” Cardman says. There’s no official requirement for any particular body type. Nor are there standards for physical fitness, like running a mile in a certain time. “It’s more functional,” she says. As long as you can meet the mental and physical demands of a spacewalk, it doesn’t matter how you get in shape.

Rethinking radiation risks

There’s one more medical requirement for the next folks to walk on the moon. They can’t have already spent too much time in space.

Over time, exposure to the harmful charged particles that zip around space can increase a person’s risk of cancer. For astronauts’ safety, NASA limits how much radiation an astronaut can absorb over their career.

From 1995 until 2021, that threshold depended on someone’s age and sex. The limit was the amount that could lead to a 3 percent risk of dying from radiation-caused cancer. Women were thought to have higher risks of dying from radiation-related cancers than men. So female astronauts were not allowed to fly as much.

Women were allowed about 150 millisieverts of radiation during their careers. Men were allowed more than five times that much. This difference may have unfairly limited female astronauts, says Erik Antonsen. An emergency physician and aerospace engineer, he works at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. No openly transgender astronauts have flown, he notes. But he can’t think of any medical issues that would hold them back.

In 2021, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine released a report urging NASA to change its radiation limit. The new limit should be 600 millisieverts of radiation for everyone, the report said. That amounts to about 400 days in orbit around the moon or 680 days on the lunar surface.

A new anti-radiation vest for women astronauts might further reduce their risk on moon missions. To test its effectiveness, a pair of dummies wore those vests on Artemis I.

Since Cardman hasn’t been to space yet, she’s as far from NASA’s radiation limit as she could be. She and her cohort are beginning to fly missions to the International Space Station and are likely candidates for Artemis III. Cardman herself could be the first woman on the moon.

She’s modest about it. “I would be thrilled to go to the moon, of course,” she says. “Depending on the timeline, who knows. But it’s pretty exciting to know I work with the people who will be the first ones setting foot [back] on the moon in half a century.”

The new right stuff

Even though there are no official astronaut health standards, NASA does end up selecting the healthiest people, Antonsen says. But private spaceflight companies are expanding the pool of people who get to space. SpaceX and Blue Origin are already sending customers on space joyrides. Those companies might be more willing to take risks than NASA is — or more focused on making money.

“The beautiful thing about this is, the goal is eventually to send just people,” Antonsen says. “It’s changing. And it should change.”

SpaceX won’t say how it chooses who it sends to space. But Antonsen suspects that some companies’ only criteria for their customers will be “making sure they can walk up the stairs to get to the vehicle.”

Even that might not be a barrier for long. Some organizations are exploring how disabled people can live and work in space.

“Disability inclusion affects how we design our spacecraft,” says AJ Link. He’s the communications director of the nonprofit AstroAccess. “If we can make [outer] space accessible, we can make any space accessible.”

AstroAccess has organized flights for disabled people on zero-gravity aircraft. Those flights aim to show that disabled people have strengths that could be useful in space. In October 2021, 12 people with various disabilities took a parabolic flight. (That’s a flight where the plane takes repeating upward and downward turns to give passengers a few minutes of weightlessness.)

“It was wicked fun,” says Sheri Wells-Jensen. She’s a linguist at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. Wells-Jensen, who is blind, was one of the people on that flight. “I’m not a thrill seeker. I don’t even like roller coasters,” she says. But while weightless, she was “surprised by how not terrified” she was.

How useless her normal instincts were also surprised her. When feeling about as weightless as she would on the moon, a tiny hop sent her flying to conk her head on the ceiling. The plane was so noisy that her normal ways of orienting by sound didn’t work. She felt like there was no up or down.

Learning how disabled people behave on spaceflights will help all astronauts in the future, regardless of disability, Wells-Jensen says.

“Space is a profoundly disabling environment. It’s always trying to kill you,” she says. What happens if an astronaut loses their vision, whether temporarily or permanently, on the way to Mars? Or if the spacecraft lights go off? Or if smoke makes it hard to see? Designing a spacecraft to be used by blind people could help all astronauts navigate those situations.

Likewise, if an astronaut loses use of their legs, knowing how people without certain limbs navigate a spacecraft will give them options. “For able-bodied people who acquire a disability in space, we’re not just going to send them home,” Wells-Jensen says. “How do we make sure they’re safe and can still do their jobs?”

Wells-Jensen hopes that sending disabled people on weightless flights will raise awareness of how capable they are. “A disabled person could take a [space] flight tomorrow,” she says. “I think at this point, the limiting factor is cultural, rather than technological.”

The European Space Agency, or ESA, is also recruiting disabled astronauts. Those astronauts include people with limb deficiencies or short stature that would normally disqualify them. These “parastronauts” will help study the kinds of adaptations needed for disabled people to travel in space. In November, ESA named its first parastronaut: John McFall. He is a British paralympic sprinter and orthopedist. His right leg was amputated at age 19 after a motorcycle accident.

Both ESA and AstroAccess argue that now is the time to consider accessibility in space. It should be done before future spacefaring vehicles are finalized. “Retrofitting is hard,” Wells-Jensen points out. “Building things the way you want them is much easier.”

That could be especially important for private companies, such as SpaceX, which are designing moon vehicles. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration oversees private spaceflight. It has not yet finalized safety regulations for private trips into space. AstroAccess wants to help guide those regulations.

“We want to fundamentally change the way humanity goes to space,” Wells-Jensen says. “We can’t become a spacefaring species if only some of us can go.”