New clues in search for Planet Nine

Hints about the distant world’s location and brightness raise hopes of actually spotting it

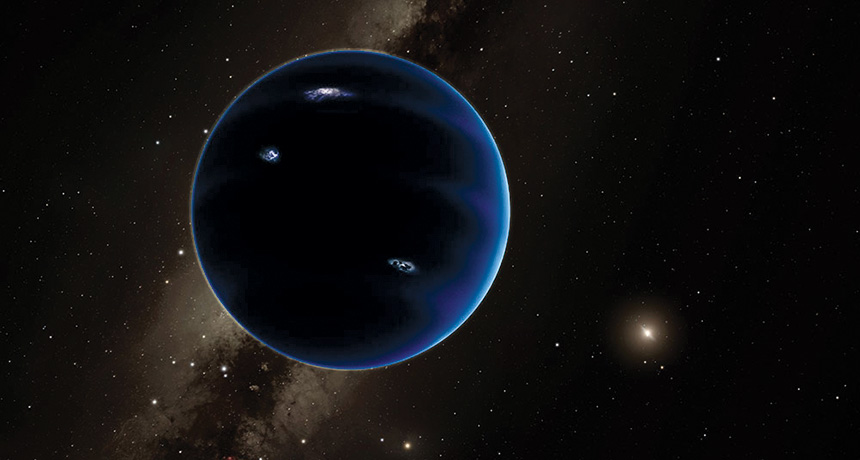

This illustration shows Planet Nine, a hypothetical new member of the solar system whose location researchers are trying to pin down.

R. HURT/IPAC, CALTECH

There may be a ninth planet lurking in the fringes of our solar system. More clues about where to search for it are coming from the Kuiper (KY-pur) belt. That’s a band of icy debris beyond Neptune. New calculations suggest the mystery planet might be brighter — and a bit easier to find — than once thought.

Evidence for a “Planet Nine” is scant. The orbits of six distant objects in the Kuiper belt seem to line up. Their oval orbits all point in roughly the same direction and lie in about the same plane. This suggests that the gravity of a hidden planet has herded them onto similar courses. Such a planet would need to be about five to 20 times as massive as Earth.

Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin announced this clue in January. Both are planetary scientists at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Now they’ve used the evidence to describe Planet Nine in more detail. Their work also homes in on where it might be hiding.

Their results appear in the June 20 Astrophysical Journal Letters.

On average, Planet Nine would likely be some 500 to 600 times farther from the sun than Earth is, Brown and Batygin say. Its orbit would be highly stretched and tipped by about 30 degrees relative to the rest of the solar system. This would take it well above and below the orbits of the eight known planets. And right now, it likely would be near its farthest point from the sun — possibly as far as 250 billion kilometers (155 billion miles) away.

But evidence that it exists is still slim. “The argument that a planet is there is not ironclad,” cautions Renu Malhotra. She’s a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “I think it’s worth studying. There’s enough there to not ignore this evidence,” she adds. “We just shouldn’t get depressed if the planet’s not there.”

Malhotra and her colleagues have been looking for other evidence of a ninth planet. And they think they’ve found another clue: The orbits of those same six frozen Kuiper belt objects all take a similar amount of time. Such synced orbits usually hint at a gravitational link among all the bodies involved. But these distant worlds are too small to affect one another, says Malhotra. That suggests there’s another, more massive world pulling all of them in line. Her team reported its finding in the same journal.

The evidence from Malhotra’s team would put Planet Nine, on average, about 665 times farther from the sun than Earth is. It would be at least 10 times as massive as Earth and circle the sun once every 17,117 years.

The synced orbits are “very intriguing and very interesting,” says Scott Sheppard. He’s a planetary scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C. “But they need more of these objects” to show the syncing isn’t just due to chance, he adds. In 2014, Sheppard and Chad Trujillo suggested that a ninth planet could explain the orbits of a dozen worlds (including those six) in the Kuiper belt. Trujillo works at the Gemini Observatory in Hilo, Hawaii.

“We want to discover more of these smaller [bodies], which are more numerous and can lead to the big one,” says Sheppard. He and Trujillo are hunting for remote Kuiper belt objects with telescopes in Chile and Hawaii. They’ve had some success in adding a few more distant lumps of ice to the collection. And the orbits of these new discoveries show hints of being in line with the others, Sheppard says.

If new objects help astronomers zero in on Planet Nine’s location, there’s a chance they could even see it directly. Its chilled atmosphere — colder than about ‒220° Celsius (-364° Fahrenheit) might contain only hydrogen and helium gases. These gases are good at reflecting light, report Jonathan Fortney and his team in the June 20 Astrophysical Journal Letters. Fortney is a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“We expect the planet, if it’s there, to be a kind of mirror,” Fortney says. “We think it would be bright with a whitish hue.” Depending on its size, Planet Nine might be even bright enough to be detected by the Dark Energy Survey. This project is scanning for new galaxies and supernovas in the southern sky. However, it also can spy on objects closer to home.

“The real problem is knowing where to look,” Fortney says.

Brown and Batygin think they’ve narrowed it down to a large patch of sky near the constellation Orion. Planet Nine, if it’s there, will be hard to find, Batygin warns. “But the reward is an expansion of our planetary family.”