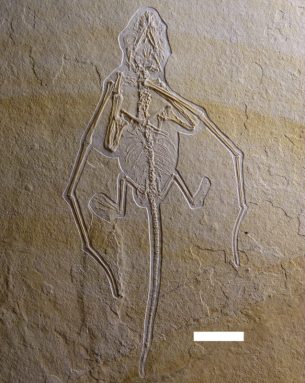

New Jurassic flier

Amazingly well-preserved fossil depicts a novel flying reptile from the age of dinosaurs

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Janet Raloff

M. Van Rooijen

David Hone of the University of Bristol in England has made a career of studying pterosaurs — flying reptiles from 100 million years ago or more. Several years back, while working in southern Germany, he visited the local Solnhofen Museum along with a lot of other pterosaur experts. As they peered into a glass museum case that held a sandy-colored, fossil-bearing rock, he recalls the scientists saying something like: “How lovely, another Rhamphorhynchus.” The fossil was nice, but tiny — and just one of some 120 or so specimens of this pterosaur from about 150 million years ago.

Except that it wasn’t.

Now that Hone has gotten up close and personal with the fossil, he can categorically admit that he and the other experts initially got it wrong. What they had quickly brushed off as a fairly common pterosaur is actually one new to science. Hone and his coworkers have named it Bellubrunnus, or Brunn beauty, in honor of the German rock quarry from which it was unearthed.

The researchers described the newfound reptile along with photos of its bone structure and what the live animal might have looked like in the July 5 issue of PLoS ONE.

Hone is a paleontologist, which means he studies the remains of prehistoric plants and animals preserved in ancient rocks. The goal of these scientists: to understand the history and evolution of life.

As a pterosaur specialist, Hone was amazed at the new fossil, even before he understood its rarity. One reason: It was amazingly complete.

D. Hone/Univ. of Bristol

Nearly all of the bones and teeth were present and in the same position they would have been in the live animal. That is quite unusual, he notes.

Pterosaurs tend to have thin bones that can break easily when compressed. And fossils form as layer upon layer of sediment piles up and eventually compresses any plant or animal remains that may have fallen onto the ground long before.

Because the new fossil came from a juvenile, it was little — just 14 centimeters (about 5.5 inches) long from the end of its snout to the tip of its tail. That diminutive size should have made it even more fragile.

Moreover, Hone notes, the bodies of pterosaurs were far more likely to decay and decompose than those of bigger ancient animals — like the dinosaurs that pterosaurs are related to. (Warning: Don’t mistakenly call a pterosaur a dinosaur. You’ll get a lot of paleontologists very upset!)

“So something this small, of this quality and with this degree of preservation is not exactly unique,” Hone says — but it’s better than 99 out of every 100 fossils of animals from this long-ago period.

Besides its amazing state of preservation, the new reptile possessed some novel features. For instance, compared to other Rhamphorhynchus-like pterosaurs, it had relatively few teeth — just 22 or so, instead of 30 or more.

And its tail would have been relatively flexible. Ordinarily, Rhamphorhynchus-like pterosaurs have tails containing lots of overlapping long, thin rods of bones — like pieces of uncooked spaghetti. Although the tail can flex a bit, the interwoven rods would have kept it fairly rigid. In all Rhamphorhynchus-like pterosaurs “you have this same tail structure,” Hone says. “Except for Bellubrunnus.” Its tail may have improved its ability to maneuver in the air, he speculates.

The outermost bone in each Bellubrunnus wing is also unique, Hone notes. In other flying bony animals — be they other pterosaurs, birds or even modern bats — that last bone “is either dead straight or it curves back a little,” he told Science News for Kids. But in Bellubrunnus, this bone curves outward. This would have made the wing a little less stable, he suspects. So the creature wouldn’t have effortlessly soared like a hawk, but it might have been especially adept at sharp turns and diving.

And how big might this guy have grown? No one knows, but Hone says that based on the size of other Rhamphorhynchus-like pterosaurs to which it appears closely related, Bellubrunnus might have attained a wingspan of up to 1 meter.

Power words

evolution A process by which species undergo changes over time, usually through genetic variation and natural selection, that leave a new type of organism better suited for its environment than the earlier type. The newer type is not necessarily more “advanced,” just better adapted to the conditions in which it developed.

fossil The hardened remains or imprint of a plant or animal that lived long ago, often found in sedimentary rock like the pterosaur here in Solnhofen.

Jurassic Lasting from about 208 million to 144 million years ago, it’s the middle period of the Mesozoic Era, a time when dinosaurs were the dominant form of life on land.

paleontology The branch of science concerned with ancient, fossilized animals and plants.

pterosaur An extinct, warm-blooded flying reptile that lived 245 million years ago to 65 million years ago.