New, older age for the universe

Telescope peers back to see the first light after the Big Bang

A new study of the age of the universe shows that it’s about 80 million years older than scientists had previously thought. For a place we now believe to be 13.81 billion years old, that few extra tens of millions of years isn’t much of a change. It’s roughly like finding out a friend is actually 13, and not just 12 years and 11 months old.

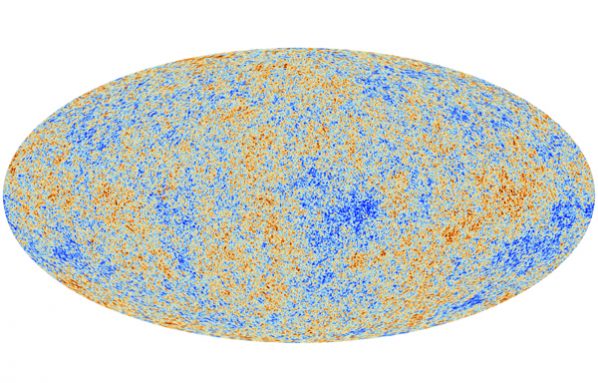

Scientists measure the age of the universe by studying what is called the cosmic microwave background radiation. That radiation is energy. And it is left over from just after the Big Bang, the violent expansion of space and energy that marked the birth of the universe. In the billions of years since then, the energy has spread almost evenly throughout the universe. (Some spots are slightly warmer; others slightly cooler.)

Now, a new study has used the European Space Agency’s Planck space telescope to make the most accurate measurement to date of that leftover energy. Planck orbits the sun and stares deep into space — and back in time. The ancient glow that reaches its instruments is the oldest light in the cosmos.

The new map of the universe created from the Planck data accomplishes two things. First, it lines up with previous maps of the universe. That is a good thing, since it doesn’t clash with older theories about the history of the universe. Second, the Planck map reveals a few unexpected quirks scattered here and there. That’s also a good thing: Studying those quirks may lead to new discoveries about the universe.

“The clarity and precision of Planck’s map is stunning,” Richard Easther told Science News. “It’s as good as anyone could have hoped for.” Easther, who did not work on the new Planck study, is an astrophysicist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

The Planck telescope acts like a sensitive thermometer. It’s not the first instrument to take the universe’s temperature, but it is the most precise. The satellite can detect even tiny changes in that background temperature. These changes, over billions of years, led to the formation of stars and galaxies.

Astrophysicist George Efstathiou from the University of Cambridge in England presented the new map at a recent meeting in Paris. He said the map may look like a “dirty rugby ball,” but is very important. He joked that in the past, some scientists “would have given up their children to get a copy.”

The Planck data line up with many theories about the early universe. One of these is called inflation. According to this theory, the universe expanded faster than the speed of light in a short burst right after the Big Bang. Inflation can help explain how the universe got so big, so fast.

The new data also give new evidence for a longstanding cosmic puzzle. There are more small changes in temperature if you look one direction in the universe than in the other. And scientists don’t know why that should be.

Some physicists hope to find that this lopsidedness will give evidence that our universe collided long ago with another universe. That’s what physicist Matthew Kleban, from New York University, will be looking for in the Planck data. For now, he told Science News, it’s too early to know for sure. However, he added, “it looks like there is some very interesting work to be done.”

Power Words

astronomy The branch of science that deals with celestial objects, space and the physical universe as a whole.

cosmology The science of the origin and development of the cosmos, or universe.

radiation Energy emitted by a source that travels through space in waves. Examples include visible light, infrared energy and microwaves.

Big Bang The rapid expansion of dense matter that, according to current theory, marked the origin of the universe.