New solar system found to have 7 Earth-size planets

Three may even orbit in the ‘Goldilocks’ zone

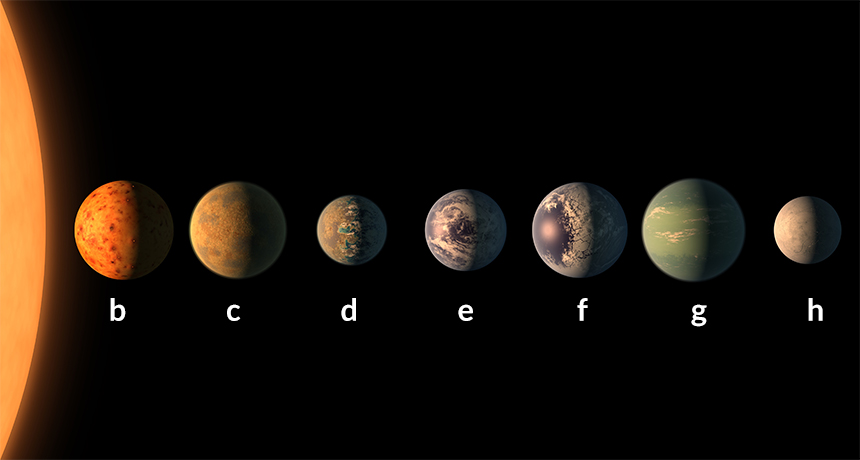

Artists’ idea of what the TRAPPIST-1 solar system might look like. For now, each of it’s Earth-sized planets is known by a letter only. Their estimated relative size is shown.

JPL-CALTECH/NASA

Astronomers have just identified a nearby solar system hosting seven Earth-sized planets. Most intriguing: Three planets that orbit its central star — known as TRAPPIST-1 — may even be within a habitable zone. That means they fall within a region that could support life as we know it. As such, these newfound worlds are good sites to focus a search for alien life.

TRAPPIST-1’s big planetary family also hints that many more cousins of Earth may exist than astronomers had thought.

“It’s rather stunning that the system has so many Earth-sized planets,” says Drake Deming. He’s an astronomer at the University of Maryland in College Park. It seems like every stable spot where a planet could be, there is an Earth-sized one. And that, he adds, “bodes well for finding habitable planets.”

Astrophysicist Michaël Gillon works at the University of Liège in Belgium. He was part of a team that last year announced they had found three Earth-sized planets around TRAPPIST-1. This dwarf star is only about the size of Jupiter. It’s also much cooler than the sun. And it’s a relative neighbor to Earth, a mere 39 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius.

Follow-up observations with the Spitzer Space Telescope and additional telescopes on the ground now show that what first had appeared to be a third planet is actually a quartet of Earth-sized ones. Three of these may be habitable.

If those planets have Earthlike atmospheres, their surfaces may even host oceans of liquid water. Or at least that’s what Gillon and his colleagues reported online February 22 in Nature. Their data also offer signs of a seventh, outermost planet.

How they spotted the new worlds

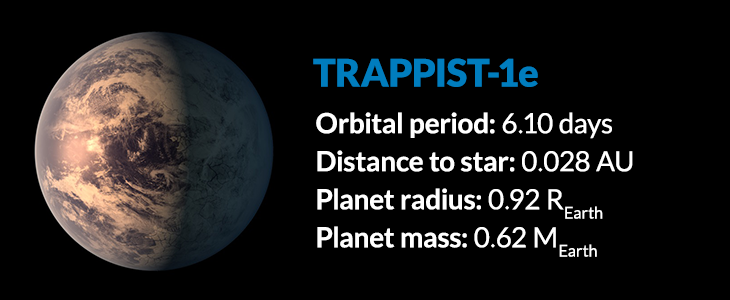

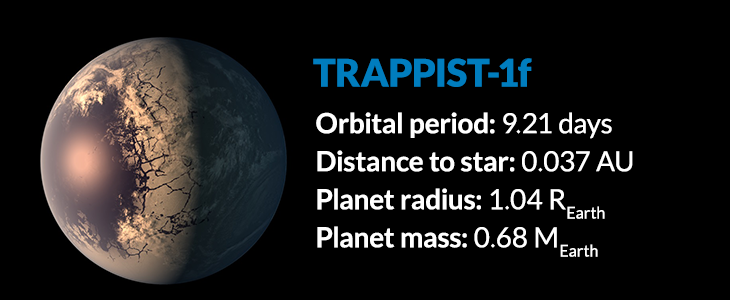

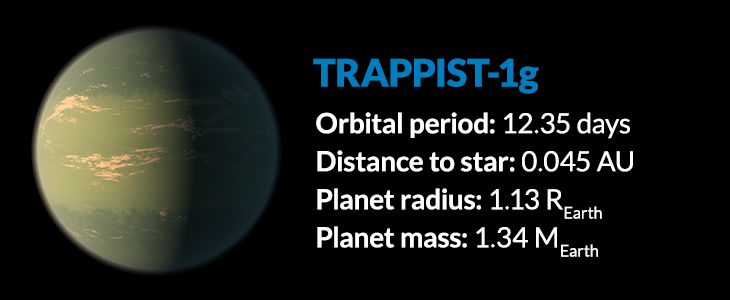

All seven planets were detected by watching how their star dims as each passes — or transits — in front of it. Scientists measured how much of the star’s light each transit blocked from Earth’s view. Knowing how big a planet would have to be to do that, the astronomer calculated that all seven must have roughly the same radius as Earth.

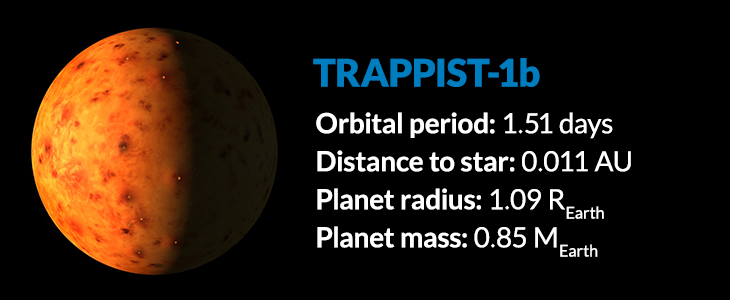

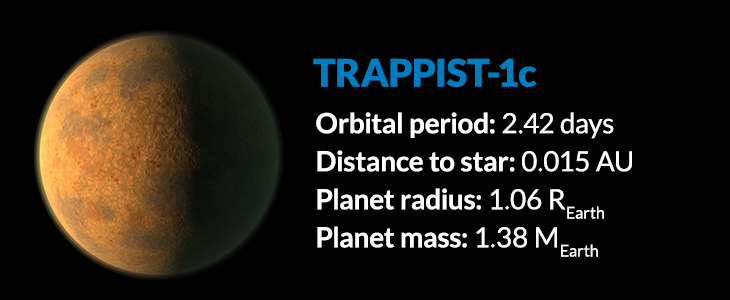

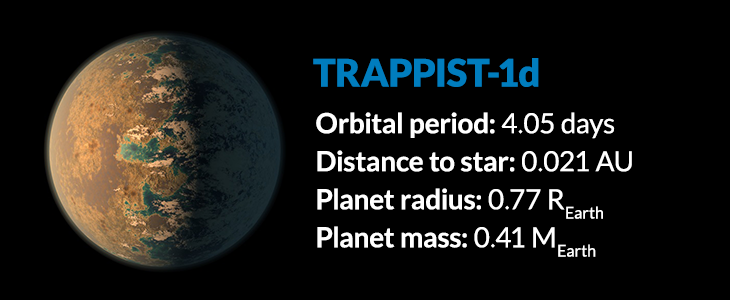

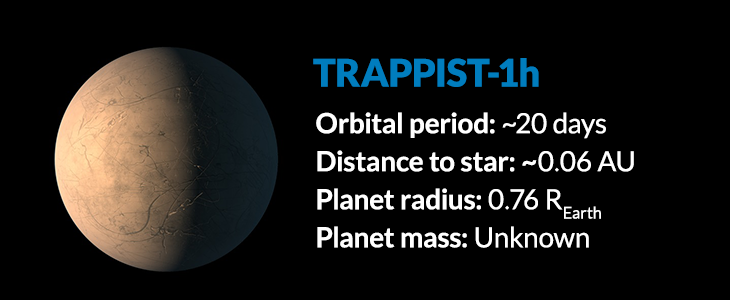

Those dips in starlight also showed how fast the planets orbit their star: The innermost one makes a round trip in 1.5 Earth days. The outermost one takes roughly 20 days.

The planets’ masses range from about half to 1.5 times that of Earth. To figure that out, the researchers looked at the way the six inner planets tug on each other. The mass and size data then allowed the team to calculate the planets’ densities. All of this suggested that the inner six are rocky, as Earth is.

The length of each planet’s day — how quickly it spins on its axis — may sync with its sun’s orbit. That would make the innermost planet’s day 1.5 Earth days long and the outermost one’s 20 Earth days long. That would be like Earth rotating once in 365 days instead of in 24 hours.

Such a spin would keep the same side of a planet facing its star all the time (much as one side of our moon always faces Earth). This would give each of TRAPPIST-1’s planets permanent day sides and night sides. Astronomers feared that would make the planets too hot on the day side and too cold on the night side to be habitable.

But if they have Earthlike atmospheres, three of the planets would still be warm enough all over to have liquid water. And that’s one requirement for a so-called livable “Goldilocks” zone — an environment that’s not too hot or cold to support life. This solar system’s seventh planet probably is icy, Gillon says, perhaps like Jupiter’s moon Europa.

(Story continues after slideshow)

“We are on the right angle to see this system and its Earth-sized planets,” notes Deming, who was not involved in the study. “For every system we see, there are dozens more that we don’t.” Stars like TRAPPIST-1 with Earth-sized planets are probably not rare, he now suspects. If they were, it could have taken many more observations to find some. In fact, the pilot project by Gillon’s group to study ultracool dwarf stars spotted one quickly. That this star had all of these Earth-size exoplanets suggests that it may be quite normal for such stars to harbor planets similar to Earth.

Studying the atmospheres of such planets could reveal if they have life. One thing to look for: the gases methane and oxygen. Astronomers can look for those atmospheres (if they exist) with the Hubble Space Telescope or its successor, the James Webb Space Telescope (which is due to launch in 2018).

Deming is cautious, however, about how easy it will be to probe for details of planetary atmospheres. The light from ultracool dwarf stars can vary, he notes. And it can be hard to understand how the planets’ atmospheres might behave.

Didier Queloz is a bit more optimistic. He’s an astronomer at the University of Cambridge, in England, and one of the new study’s authors. “We have no idea what these planets look like now. They could be wet or dry. We just don’t know,” he says. “But for the first time since the first exoplanet was discovered 25 years ago, we may be able to answer the question about life beyond our solar system.”