New success in treating allergies to peanuts and other foods

Some treatments can train the immune system to react less to proteins that normally send it into overdrive

Many children love peanuts and the “butter” made from them. But for some people allergic to these legumes, it can take less than a third of a peanut (or its equivalent) to trigger a dangerous allergic reaction.

AtlasStudio/ iStock/Getty Images Plus

Ten years ago at a kindergarten party, Isaac Judy took a bite of a peanut-butter cookie. It tasted weird to him, so he spit it out. Hives soon appeared on his face. His lips also began to swell. When his dad came to pick him up, Isaac was coughing and wheezing. Riding in the car to the other side of St. Louis, Mo., where they lived, Isaac fell asleep — or so it seemed.

When Isaac’s mother saw what was happening, she suspected something more serious. “He hadn’t fallen asleep. He lost consciousness,” Jaelithe Judy explains. After a trip to the emergency room, her five-year-old recovered. But doctors confirmed her hunch: Isaac has a peanut allergy.

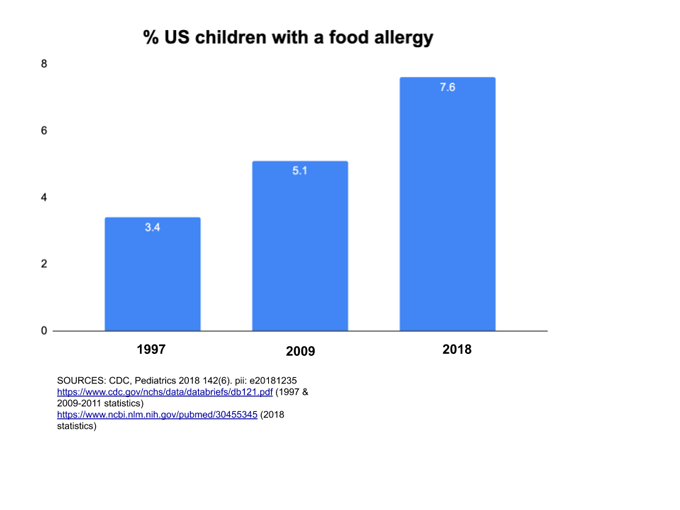

Just a few generations ago, hardly anyone talked about food allergies. But over the past two decades, childhood food allergies in the United States have more than doubled. A little more than a year ago, a study in Pediatrics reported that 7.6 percent of U.S. kids under age 18 have food allergies. That’s almost 8 million youth — about two students per classroom. And it’s much more than a childhood issue. Surprisingly, a study last year in JAMA Network Open found that nearly 11 percent of adults have food allergies, too. More than one in every four of them said they had not been allergic to foods as children.

These days nearly everyone has “come across a family member or person who has been touched by food allergies, or has one themselves,” says Tamara Hubbard. She works in the suburbs of Chicago, Ill., as a licensed counselor. Hubbard and a growing number of counselors are helping families through the stress of managing food allergies.

For years, doctors have told families there’s nothing they can do but avoid the trigger food — or inject a fast-acting medication called epinephrine (Ep-ih-NEF-rinn) to stop a severe reaction. But researchers are learning more about why some people overreact to certain foods. And new treatments are emerging. Late last month, the first treatment for peanut allergy earned approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Another could do so within a year or so. Scientists also are continuing to develop and test other ways to treat food allergies.

Immunity run amok

Allergic reactions occur when the immune system overreacts. Normally immune cells help fight bacteria, viruses and other pathogens. Yet some people’s immune systems also react to harmless stuff like pollen or mold — or peanuts, milk or other foods.

Such run-ins trigger a release of histamine (HIS-tuh-meen) and other chemicals. These molecules “get the ball rolling for an allergic reaction,” explains Tina Sindher. She works as an allergist at Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

During an allergic reaction, someone may get itchy and develop hives. If the reaction worsens, the person might cough, wheeze and suffer a whole-body reaction known as anaphylaxis (An-uh-fuh-LAX-iss). That’s what happened to Isaac — and to Shea Tritt’s son, Gaines, in Abingdon, Va.

Gaines’ peanut allergy surfaced in the fall of 2012. At the time, he was a baby and his diagnosis put the whole family on edge. For the next few years “he never trick-or-treated. He never went to a birthday party. I was scared to put him in preschool,” says Tritt. “My husband and I had a lot of stress because he could tell I wasn’t letting Gaines do normal things. So we would argue.”

Even Gaines’ older sister got nervous. If she went to a party, she worried about bringing back traces of peanut-containing treats that might sicken her brother, Tritt recalls. Living in such constant vigilance can be emotionally draining for families with food allergies.

Anxious and desperate, Tritt wondered if her son would outgrow his allergies, and how she could ever find out. “I became obsessed with information — anything I could do to get us out of this situation,” she says.

When a kiss can make you sick

Silly greeting cards often depict a kiss on the cheek of a cartoon figure as a big red imprint of lips. For people with a serious food allergy, real kisses sometimes leave the same mark. But it’s not funny. That red wheal signals an allergic hypersensitivity to food residues on the smoocher’s mouth.

One renowned study at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine surveyed 379 people with especially severe allergies to peanuts, tree nuts or seeds. Twenty had experienced hives or other symptoms after a kiss. In all but one case, the kisser had eaten nuts up to 6 hours earlier; at least four had first brushed their teeth.

Most reactions proved mild. But five people developed wheezing or flushing with light-headedness — potentially dangerous signs. And one three-year old was rushed to the hospital to treat respiratory distress after his mother pecked him on the cheek. — Janet Raloff

One day, Tritt saw a TV interview with David Stukus. He’s an allergist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. Stukus saw that many patients with food allergy are fearful. They often are confused because they’re not getting the facts they need. So Stukus opened a Twitter account to spread evidence-based information. Tritt took note.

Looking at her son’s blood-test results, year after year, Tritt suspected his immune response to peanuts was lessening. However, blood tests cannot give a clear “yes” or “no.” These tests detect specialized immune proteins. They are called IgE antibodies. These molecules trigger allergic reactions. But IgE levels only indicate that someone is sensitive to a certain food. They cannot predict whether that person will react if they eat it. Proving Gaines had outgrown his peanut allergy would require an oral food challenge. And that would require that the patient eat increasing amounts of the food while a doctor watches for allergic reactions.

Trouble is, Tritt could not find a local allergist to perform the food challenge. This procedure needs extra time and staff. It also runs a risk of triggering anaphylaxis. So, many clinics won’t offer it unless a patient’s blood results are low — low enough to suggest they would tolerate the food. Gaines’ numbers had steadily dropped over the years but were still a tad too high.

Peanuts: Becoming bite-proof

For about half of people with peanut allergies, “a bite or two of the wrong food typically contains enough peanut protein to trigger a reaction,” notes Brian Vickery. He is a pediatric allergist at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. For these people, he says, 100 milligrams (0.004 ounce) of peanut protein, or about one-third of a peanut kernel, can set off such a reaction.

Vickery used to work at Aimmune Therapeutics. This California company has developed a new treatment for peanut allergy. It is called oral immunotherapy, or OIT for short. The procedure involves each day eating a wee bit of peanut protein — pre-measured into capsules. The capsule dose goes up every few weeks over a period of months. If the treatment works, it can raise the immune system’s threshold for the food. That means it would take more of the food to trigger an allergic reaction. In other words, it’s possible for the person to become “bite-proof.”

Aimmune tested its capsules — or a dummy version called a placebo — in 551 children and teens with peanut allergies. The starting dose was half a milligram (0.00002 ounce) of peanut protein. (One peanut contains 600 times that much.) Over a six-month period, the daily dose went up to 300 milligrams (0.01 ounce), or about one peanut’s worth. And each day for six more months, participants had to continue eating that much.

During the study, many participants experienced allergic reactions to the peanut pills. Forty-three of those being treated quit because of these unpleasant symptoms. But among those who finished the study, two-thirds of the treated group became bite-proof. After about a year, they could safely eat roughly two peanuts. “They’re still careful about avoiding peanuts,” says Vickery. “But it provides that additional margin of safety.”

Those results appeared in the November 2018 New England Journal of Medicine.

Based on these and other findings, the FDA approved those peanut capsules on January 31.

Similar work underway

Over the past decade and prior to the FDA approval, a small number of allergists had already started offering OIT using store-bought foods. Tritt found one such clinic several hours away. However, that clinic was not willing to give her son a peanut challenge to confirm whether he still was allergic.

Tritt didn’t want to sign her son up for a long, costly treatment if he might in fact be outgrowing his allergy. But they couldn’t know for sure without the gold-standard test, that oral food challenge.

She discussed her dilemma with Stukus on Twitter. Reviewing Gaines’ blood-test results, Stukus agreed to conduct the food challenge. Just before Gaines started kindergarten, his family travelled from Virginia to the doctor’s clinic in Ohio. It was a nine-hour drive.

Gaines started the challenge with a “small, laughable amount” of peanut butter, Tritt recalls. Fifteen minutes later, he ate a bit more. Then some more. Over several hours he chomped a dozen Reese’s peanut butter cups. And he never reacted.

The test proved Gaines had outgrown his allergy. That makes him one of the lucky few. Many children outgrow some food allergies by the time they enter school. But eight out of every 10 kids with allergies to peanuts or tree nuts will remain allergic.

Freedom and failure

Gian Lagemann, a high school senior in Saratoga, Calif., is allergic to 11 kinds of nuts, including peanuts (which actually is not a nut; it’s a legume). When he started kindergarten, his mother brought “no nuts allowed” signs to the classroom. She asked other parents to tell her whenever they brought in food — so she could make sure it was safe for Gian. Every day Gian ate his lunch at a designated peanut-free table.

Several years ago, Gian’s mom told her son about a peanut OIT trial. The study was starting nearby at Stanford University. “For most of my life, I haven’t been able to eat things where the ingredient labels say ‘may contain peanuts’ or ‘processed in a facility with peanuts,’” Gian says. “Once she explained that [after the trial] I’d be able to eat those foods, I was pretty happy. I was sold.”

At the start of the trial, his family bought a bag of peanut flour. For about six months, Gian took his dose each day after dinner. He doesn’t like the taste of peanuts. So he often mixed his dose into a spoonful of chocolate ice cream. The dose started at 1.3 milligrams of peanut protein (about 1/200th the amount in a peanut). Over the six-month trial it went up to 240 milligrams (0.008 ounce, or a little less than one peanut’s worth).

More broadly, some 8,000 U.S. patients have tried such an oral therapy. Typically, about one in five will withdraw because of side effects or anxiety. Completing such a trial takes focus and discipline — like playing sports. But, Gian recalls, “They told us with every dose we took, our body was just going to get stronger.”

Participants also learned to expect some allergic reactions. “If you’re going to build your immune muscle against a food allergy, you know you’re going to have a little ‘ache’ during the process,” says Kari Nadeau. This Stanford allergist was a leader of the trial.

Gian felt a few such responses during the study. “My throat would feel a little tight for 15 minutes,” he says. “But after that, it was fine.” So he persevered. And it paid off. When the trial ended, he could eat a full peanut without having an allergic reaction. That means Gian now can safely eat candy with labels warning they’re made in facilities that process nuts. “I was able to try Kit Kats for the first time, and Milky Ways,” Gian says.

Two years ago, Isaac also tried this oral peanut therapy. At the time, he was 13. But his experiences were quite different. During the treatment he suffered sinus and gastrointestinal troubles. He also had an anaphylactic reaction. Six months in, Isaac dropped out. He quit because he had developed an immune condition called eosinophilic esophagitis (Ee-oh-sin-oh-FILL-ick Ee-SOF-uh-JY-tis). The oral therapy triggers it in a small share of people.

And there’s something else to keep in mind: People could lose their desensitization to peanut once they end the oral therapy. That finding was confirmed in a 2019 study by Nadeau’s team. For many people, effective treatment might have to continue long-term.

Other treatments

Some people have taken part in research trials testing a different treatment for peanut allergy — a skin patch. Instead of eating bits of peanut by mouth, patients every day stick a coin-sized disc onto their back or upper arm. Each disc contains a quarter-milligram of peanut protein. That’s about a thousandth as much as what’s in a peanut. (By comparison, Aimmune’s capsules start with twice that much. Over months, patients then take doses that increase to 1, 10, 20, 100 and 300 milligrams.) From the patch, peanut proteins seep through the skin but do not enter the blood. Peanut patches are therefore less likely to cause anaphylaxis than is the oral therapy.

DBV Technologies in France makes the patch. This company conducted a year-long trial of its product in 356 children with peanut allergies. Nine in every 10 participants finished the trial. The most common side effect was a skin rash at the patch site. However, this trial didn’t work as well as the company had hoped. By the end of the study, only a little more than one in every three patients treated could safely eat the “exit dose” of one to three peanuts. The study leaders reported their findings in the March 12, 2019 Journal of the American Medical Association.

Still, the patch has worked wonders for some. In 2012, Sharon Wong was desperate. Her son’s allergies to peanuts and tree nuts had intensified to an alarming degree. Once during a shopping trip, he went into a coughing fit while walking past a batch of freshly baked walnut cookies. At a restaurant buffet, he started vomiting after merely looking at a steamy tray of pesto pasta. (Pesto is made with pine nuts.)

“It was really awful,” recalls Wong. “We cannot control the air he breathes. But we didn’t want to keep him confined at home. We wanted him to be able to go shopping, to go down the street, to go to friends’ homes and not stress about his allergies.”

That year she enrolled her son, then nine years old, in an earlier-stage peanut patch trial in the San Francisco Bay area of California. At first, it took just 1/240th of a peanut to trigger an allergic reaction. After two years on the patch, he could tolerate about six peanuts.

“We feel more comfortable about traveling longer distances and dining in restaurants with precautions in place,” Wong wrote in a blog about the patch trial. “Each mini-success gives us confidence and improves our quality of life. My son is happier and healthier.”

In August, the FDA plans to review data on the peanut patch and recommend if it should be approved. DBV Technologies is also researching and developing patches to treat milk and egg allergies. And as for oral therapies, Aimmune recently started a new trial for its egg-allergy treatment. The company is also developing an oral therapy for allergy to walnuts, cashews or hazelnuts.

Scientists are studying other related approaches, too. One is an immune therapy that uses liquid droplets containing allergens. These are placed under the tongue rather than swallowed directly. Edwin Kim, an allergist at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, in Chapel Hill, led one study of children treated for three to five years with this sublingual therapy. All had peanut allergies. Of the 37 kids who completed the study, two in every three could now consume 750 milligrams (0.03 ounce) or more of the peanut allergen. Kim, whose center has helped conduct studies for DBV and Aimmune (among other companies), reported the findings last November in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Additional experimental treatments block other parts of the immune response to allergens. Some act together with oral therapy, allowing fewer allergic reactions during therapy. Others supply helpful gut microbes that seem to guard against food allergies. And one company is developing a toothpaste to treat peanut allergy.

In the end, each family must decide whether to seek an emerging treatment or stick with just avoiding exposure to the sensitizing foods. Treatments require diligence. They’re not yet widely available. And they don’t always work. But if the allergy is unbearable, trying a new treatment might prove worth the time and risk. Clearly, concludes Stukus, the Ohio doctor, “food-allergy management is not one-size-fits-all.”