New virus may have given kids polio-like symptoms

Evidence strengthens a link between this new germ and a mystery illness that has paralyzed U.S. children.

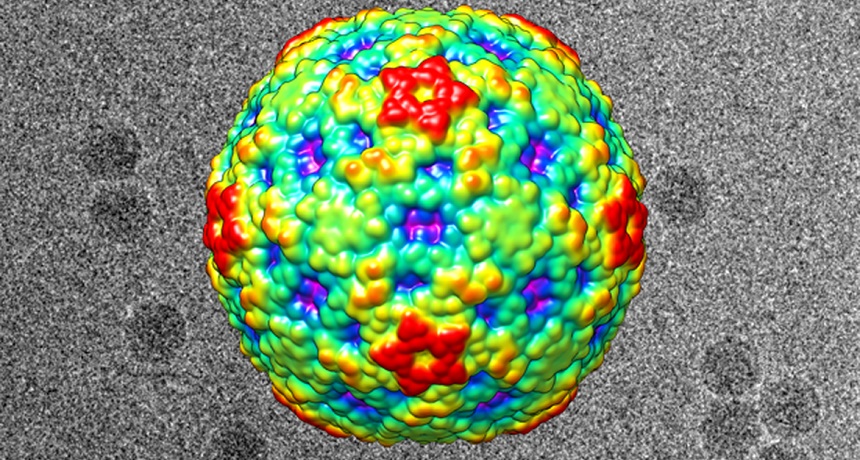

A 3-D image of enterovirus D68 (center) was created from electron microscope images (background). This virus might be responsible for a polio-like illness in U.S. kids.

Yue Lin and Michael Rossmann, Purdue Univ.

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Last year, a nasty virus swept across the United States. Called enterovirus D68, it initially left its victims sneezing and coughing. Some even struggled to breathe. But quite a few of these people also developed an even scarier symptom: limbs that could not move. Almost all victims of this paralysis were kids. New evidence now links those polio-like symptoms to a new type of the virus.

Doctors are now referring to the paralytic illness as acute flaccid myelitis (Ah-KUTE FLAA-sid MY-eh-LY-tis). Since August 2, 2014, government health officials say the illness has sickened 115 children in 34 states. It damages nerve cells in the spinal cord that control muscles. This can make it hard to move the arms or legs. If nerves in the head also become damaged, paralysis can affect the face. Sometimes vision may become blurred. In very bad cases, patients may not be able to breathe on their own.

The U.S. outbreak of the D68 virus developed at the same time as the paralysis. That suggested the two might be linked. And it wasn’t hard to believe. After all, polio — perhaps the disease best known for paralyzing people — also is an enterovirus. (Fortunately, vaccinations have nearly wiped out polio in the past few decades.) Still, the infection and paralysis might have been a coincidence.

Hoping to find out if the apparent link was real, researchers dug into the evidence. What they found does not prove this enterovirus can paralyze muscles. Still, the scientists report in the March 30 Lancet Infectious Diseases, links between this virus and paralysis are getting stronger.

What the genes show

Charles Chiu oversaw the new study. A doctor, he works at the University of California, San Francisco. His team looked at data from 25 people with acute flaccid myelitis. All lived in Colorado or California. The D68 virus showed up in samples swabbed from the noses and throats of 12 patients, or nearly half. Chiu thinks the rest of the patients could have had the virus too. They might simply have been swabbed too late to find the virus, he explains.

Chiu’s team also studied cerebrospinal (Seh-REE-bro-SPY-nul) fluid from the paralyzed kids. Scientists would expect to find evidence in this fluid of any germs that had attacked the spinal cord. But no D68 virus emerged. While unusual, this is not unheard of, Chiu notes. The polio virus, too, tends not to hang out in spinal fluid.

The researchers then used genetic tools to search for signs of other viruses, bacteria, fungi or parasites that might have caused disease. No sign of these showed up in the spinal fluid either. This means there’s still no alternative suspect in the case.

It’s technically possible that some other infectious germ is causing the paralysis and hiding outside of the spinal fluid. But that’s not likely, Chiu contends. Taken together, he says, his team’s new data “make a strong argument” that D68 is the culprit.

Disease is new version of known disease

All D68 patients in Chiu’s study had the same type, or strain, of this virus. The researchers discovered this by investigating the germ’s genes.

Machines can “read” the order of the molecules that serve as letters in the genetic code. The genes in each strain of a virus will be slightly different. Often this gives these organisms different traits.The D68 strain seen in the paralyzed children showed up for the first time in 2010. The changes in its genes, also known as mutations, may allow it to damage nerve cells, weakening muscles.

If this new form of the D68 virus causes acute flaccid myelitis, it may do so by attacking nerve cells directly. Or the virus might turn on a victim’s immune system in a way that makes the body turn against its own nerve cells. However the virus works, it doesn’t affect everyone in the same way. Two siblings in Colorado both picked up the same D68 strain. Yet while one ended up with acute flaccid myelitis, the other sibling developed only cold-like symptoms.

This study is “another brick in the wall” that goes toward proving D68 causes acute flaccid myelitis, says Ken Tyler. He is a neurologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Although he treated some kids with acute flaccid myelitis, he was not involved in the new study.

Acute flaccid myelitis has no cure. But if doctors can confirm that D68 is its cause, they can start working on a drug or vaccine to fight this germ. A recent study of the structure of D68 viruses might help them do that. Researchers at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., published those findings on that structure in the January 2 issue of Science.

Most kids struck last year with acute flaccid myelitis still have symptoms. Yet Tyler says the patients he’s seen remain hopeful. Many also are making progress through physical therapy. One of them even wrote about the experience for his college application essay.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

acute flaccid myelitis A type of spinal-cord inflammation, first identified in 2014. Nerve cells that run through the spinal cord may become damaged. This may weaken or even paralyze muscles in the arms and/or legs. The condition most often affects children.

cerebrospinal fluid A clear liquid that surrounds and cushions (protects) the brain and spinal cord.

enterovirus A common family of viruses that can cause mild, cold-like symptoms or more severe illnesses.

flaccid Weak or limp; lacking strength.

germ Any one-celled microorganism, such as a bacterium, fungal species or virus particle. Some germs cause disease. Others can promote the health of higher-order organisms, including birds and mammals. The health effects of most germs, however, remain unknown.

immune system The collection of cells and their responses that help the body fight off infections and deal with foreign substances that may provoke allergies.

myelitis An inflammation of the spinal cord, which serves as a bridge to relay messages between the brain and rest of the body.

neurology A research field that studies the anatomy and function of the brain and nerves. People who work in this field are known as neurologists (if they are medical doctors) or neuroscientists if they are researchers with a PhD.

outbreak The sudden emergence of disease in a population of people or animals. The term may also be applied to the sudden emergence of devastating natural phenomena, such as earthquakes or tornadoes.

paralysis The inability to willfully move muscles in one or more parts of the body. In some cases, nerves that carry the signal to move may have been severed or damaged. In other cases, the brain may be the source of the problem: It may fail to understand or act on a nerve’s signal to move.

parasite An organism that gets benefits from another species, called a host, but doesn’t provide it any benefits. Classic examples of parasites include ticks, fleas and tapeworms.

sibling A brother or sister.

spinal cord A cylindrical bundle of nerve fibers and associated tissue. It is enclosed in the spine and connects nearly all parts of the body to the brain, with which it forms the central nervous system.

strain (in biology) Organisms that belong to the same species that share some small but definable characteristics. For example, biologists breed certain strains of mice that may have a particular susceptibility to disease. Certain bacteria or viruses may develop one or more mutations that turn them into a new strain — one that may be immune to the ordinarily lethal effect of one or more drugs.

vaccine A biological mixture that resembles a disease-causing agent. It is given to help the body create immunity to a particular disease. The injections used to administer most vaccines are known as vaccinations.