Nicotine from smoke enters body through the skin

Breathing isn’t the only way into the body for harmful chemicals in tobacco smoke

Tobacco smoke can linger long after smokers have exhaled their last puff. A new study finds that chemicals in that smoke, including nicotine, can enter the body of others in that room — through their skin.

CristiNistor/ iStockphoto

Breathing isn’t the only way that chemicals in cigarette smoke can enter the body. A new study shows that nicotine, a toxic chemical, can pass through skin and into the blood from the air or from smoky clothes.

Scientists refer to the airborne particles exhaled by a smoker as “secondhand” smoke. That’s because this smoke has already exposed the smoker and is now available to pollute the room and anyone in it. Those particles can linger for hours. “The way we are exposed to secondhand smoking is not as simple as we had thought,” says Gabriel Bekö. A civil engineer at the Technical University of Denmark in Lyngby, he led the new study.

The new findings are especially important for kids and teens, Bekö’s group says. After all, nicotine can affect their brains. So, “If you’re in a room where smoking or vaping is occurring, you’re taking in the smoke through your skin as well as your lungs,” says Charles Weschler. He’s a chemist at Rutgers University in Piscataway, N.J. A co-author on the new study, Weschler has spent many years studying the chemicals that pollute indoor air and how they get there.

It’s no surprise that tobacco’s nicotine can pass through the skin. Farm workers can get sick if too much nicotine rubs onto them from tobacco leaves. And nicotine patches have been designed to deliver the chemical dermally — through the skin. There, the goal is to help people get their fix of this addictive stimulant as they attempt to quit smoking.

But keeping skin exposures to nicotine low is important. This chemical is toxic. It has been used as a pesticide. It also can sicken — even kill — people if they are exposed to too much (such as if liquid nicotine spills onto their skin).

Against this backdrop, Weschler, Bekö and their colleagues in Denmark and Germany wanted to test whether nicotine from secondhand smoke could enter skin from a room’s air. And it can, their new data show. The study was published August 24 in Indoor Air.

“What’s new here is that the researchers have now shown that a meaningful uptake of nicotine is possible from dermal exposure to secondhand smoke,” says Frederick Frasch. He’s a scientist at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in Morgantown, W.V. He specializes in studying skin exposures to chemicals. He was not involved in the new study.

The dose was not trivial

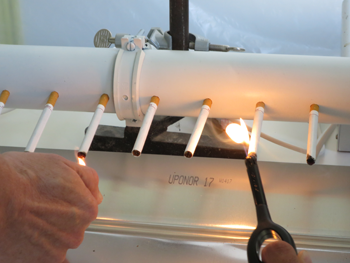

For the new tests, two nonsmoking researchers spent three hours in a closed room filled with tobacco smoke. The amount to which these men were exposed was similar to what might be found in a very smoky bar or nightclub. But it was higher than what would be found in most smokers’ homes, Weschler adds.

The men wore only shorts. This kept plenty of bare skin exposed to the smoke. And throughout the test, the men breathed clean air that was pumped to their faces through enclosed hoods. Those hoods meant any nicotine that entered their body must have come from something other than breathing.

Nicotine begins to break down once it reaches the blood. The breakdown chemicals exit the body in urine. Urine from the two researchers showed a spike in markers of nicotine exposure — those breakdown chemicals.

The men who took part had absorbed about 570 micrograms of nicotine through their skin, the data showed. That’s as much nicotine as would be picked up by smoking between 0.5 and 6 cigarettes. It’s also about as much nicotine as a person could expect to inhale in a really smoky room, says Bekö.

The researchers also wanted to find out what role clothes might play in someone’s exposure. So they hung a tee shirt for five days in a room where cigarettes had been smoked. Afterward, one nonsmoking researcher wore that shirt.

Nicotine breakdown chemicals showed up in his urine too. The scientists found that he had four times more nicotine in his blood after wearing the smoke-exposed shirt than when he wore a clean shirt.

What to make of the new findings

These data show that “nicotine is a sticky molecule,” observes William Nazaroff. So even hours after any smoking has stopped, he notes, “You can still be exposed to some of the harmful products of smoking.” Nazaroff studies pollutants in indoor air at the University of California, Berkeley. He did not take part in the new research.

It’s too soon to draw any firm conclusions from one small study, he says. More research is needed to better understand how nicotine moves through the skin. It may not move at the same rate in people with different skin types or ages. This study, for instance, looked at only three men. All were between the ages of 35 and 67. Future studies should look at women and young adults too, he says.

Future studies also could test for meaningful nicotine uptake in less smoky conditions, ones that would model the air in the house of a light or moderate smoker, says Frasch.

Last year, Weschler and Bekö showed that chemicals emitted from plastics and common household products can seep from the air through our skin. Taken together, Nazaroff says, these studies are challenging the way scientists have long thought about skin exposures to chemicals.

“We always thought you needed to touch a surface for a chemical to stick to the skin. What these new studies show is that for some chemicals you don’t need that physical contact,” he says. “They can be taken up directly from the air.”