Scientists want to create a sort of Noah’s Ark on the moon

It would bank cells from animals and other organisms in cold storage

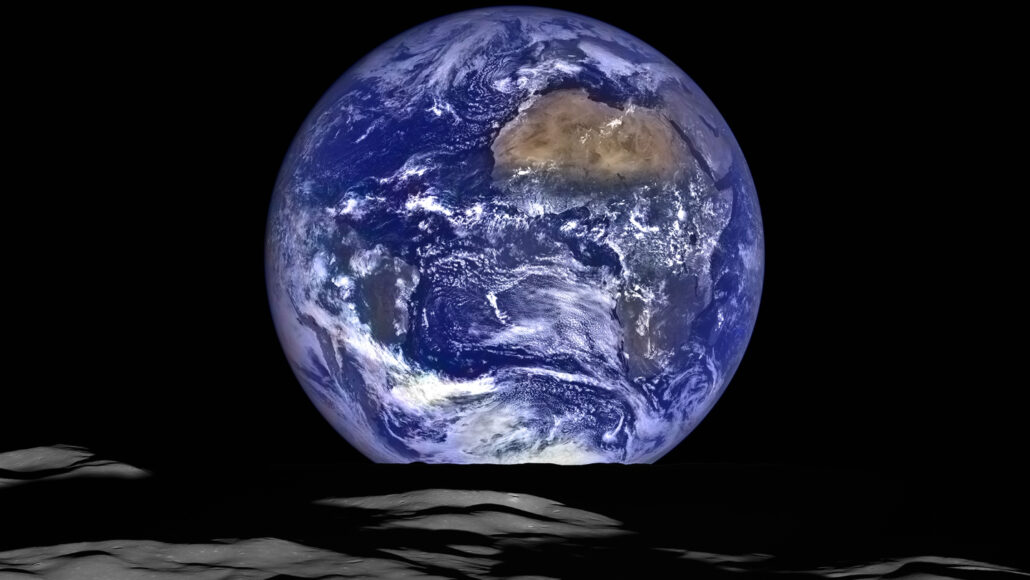

A NASA spacecraft orbiting the moon captured this image of Earth. As threats from climate change and human activities mount on our planet, scientists are proposing to build a bank holding genetic material that could preserve samples of some of Earth’s most valued species.

GSFC/NASA, ASU

As more and more species near extinction, scientists have been collecting samples of plants, animals and other organisms. They’ve been storing these cells, seeds and other materials in protected facilities across the globe. But climate change, environmental disasters and wars can threaten these modern Noah’s Arks. Now, some researchers have proposed an out-of-this-world solution: Build one of these arks on the moon.

They’d build it in a permanently shadowed site at the moon’s south pole. Temperatures there should remain a very frigid –196° Celsius (-320.8° Fahrenheit). That’s the minimum needed to safely store most animal cells long-term, Mary Hagedorn and her team noted July 31 in BioScience.

And that, they argue, should make such this gene bank far more stable than any of those on Earth.

“When it comes to saving our biodiversity and life on Earth,” says Hagedorn, “it’s very good to have as many plans as possible.” A marine biologist, she works at the Smithsonian National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute in Washington, D.C.

Not the first quest for a lunar ark

Hagedorn’s team was inspired by the global seed vault in Svalbard, Norway. Think of it as a frozen Noah’s Ark, way above the Arctic Circle. Several other seed and tissue banks around the world, too, store prized samples of organisms that are of interest to crop and livestock farmers.

Scientists collected the seeds banked at Svalbard from around the world. This facility takes advantage of the site’s freezing temps to protect its millions of stored seeds. If needed, they can be defrosted and reproduced. Later, daughter seeds can be sown at sites where these plants may no longer exist.

But in 2017, scientists learned this ark was at risk.

Melting permafrost flooded the vault. That put its precious seeds at risk of defrosting and going bad. Events like this one, researchers say, point to the need for another backup plan.

Indeed, two years ago, Álvaro Díaz-Flores and some coworkers at the University of Arizona proposed their own idea for a lunar ark. Theirs would “shelter seeds, sperms, eggs, and DNA of endangered animal and plant species of Earth.”

They’d stash collected cells or tissues in caves below the moon’s surface. Called lava tubes, the caves likely formed when underground rivers of molten rock ran dry. A solar-powered system would keep things cold. But if it ever lost power, the stored samples likely would go bad.

In the moon’s forever-frozen shadowed regions, a lunar vault would need no energy or constant human maintenance, Hagedorn’s team notes. And given the south pole’s low temperatures, she says, a vault there could store fibroblasts — “one of the most powerful cells that we have today.”

Scientists can transform these animal cells into stem cells. “Then those stem cells can be used for cloning,” Hagedorn says. Fibroblasts could be valuable for rebuilding populations of threatened or extinct species. Or they might help recreate ecosystems in future human colonies on the moon or Mars.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

What will it take to build a lunar ark?

The new proposal would have its share of hurdles. These include what to do about radiation and the long-term effects of microgravity on stored samples. Hagedorn’s team is designing radiation-proof containers for samples brought up from Earth. The next step would be to test prototypes on a future moon mission.

“The authors do a good job laying out many of the challenges,” says Benjamin Greenhagen. He’s a lunar scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. It’s in Laurel, Md. But he notes that the moon’s permanently dark regions aren’t immune to broad swings in temperature as more or less reflected sunlight can shine into the shadows. Such sites “are still cold,” he says. Still, he worries, they might not always be cold enough for this project “without some level of … management.”

By far, the biggest challenge will be getting everyone in the scientific community to largely agree, Hagedorn says. Then nations would need to work together on the plan.

Greenhagen also notes there “are communities on Earth to whom the moon is sacred.” Those who want to build a lunar ark should actively “engage these communities” if they hope to ever bank biological samples on the moon.

Hagedorn’s group argues that the first samples targeted for lunar storage should include endangered species, pollinators, ecology-building species and species that have the potential to help humans during space exploration. But planning for this project is still in its early stages. As such, she notes, “nothing’s set in stone at this point.”