Too much noise can harm far more than our ears

Besides damaging hearing, it can also disrupt learning, stress us out and more

Noise can harm your ears, brain — and ability to learn.

AaronAmat/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Sophie Balk loved to dance. She used to take part in dance competitions, doing West Coast Swing — a bouncy, twirly partner dance. At first, the music’s volume didn’t bother her. But after a while, her ears began to hurt. Sometimes her ears were ringing as she left the dance club. Balk eventually developed a hearing disorder called tinnitus — a nonstop ringing in her ears.

“When we go out into the sun, we protect our skin from sunburn by covering it up or wearing sunscreen,” Balk says. But, she notes, “We don’t think about protecting our hearing in the same way.” Balk is a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore in New York City. She now teaches other doctors about the risks posed by noise.

Loud sounds are a major environmental source of health problems. In some places, it ranks second only to air pollution, the World Health Organization notes.

When it comes to noise, hearing problems are the best known risk. But emerging research is uncovering how noise also affects the brain. It’s showing how even sounds that don’t trigger hearing loss can still harm us. Sounds from cars, lawnmowers and other everyday sources are being linked to stress, poor sleep, learning problems — even heart disease.

Clearly, noise is far more than just a pesky irritant.

How noise harms hearing

We’ve known for centuries that too much noise can cause hearing loss, says Richard Neitzel. He works at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Some 200 years ago, accounts described blacksmiths who developed hearing loss from their constant hammering of metal.

Neitzel is an industrial hygienist, someone who studies how to keep people healthy at work. Most of what we know about noise and health, he says, comes from studying workers in loud jobs.

Very loud sounds can damage tiny cells deep inside our ears. Called hair cells, they pick up sound vibrations from the air. Loud sounds also can damage the auditory nerve that carries signals from those hair cells to the brain.

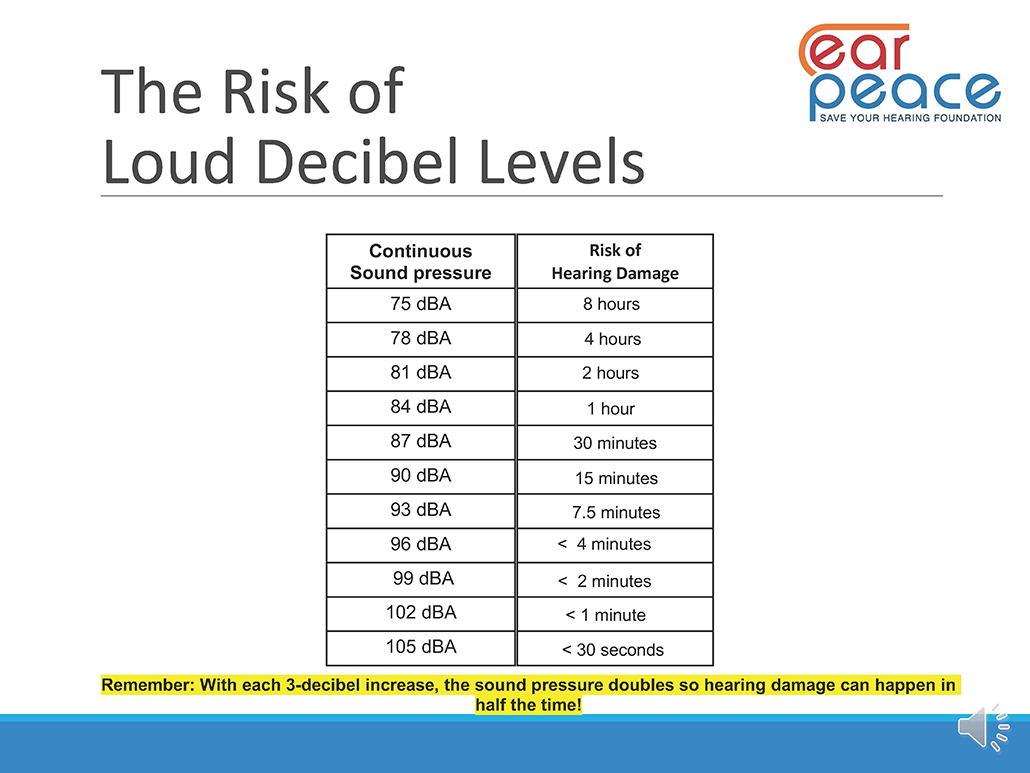

The risks posed by any given sound will depend on its volume, its pitch and how long it lasts. The softest sound we can hear is termed zero decibels. We typically converse at around 60 decibels. Gas-powered lawn mowers roar at some 95 decibels.

Audible sounds between 100 and 120 decibels can start to feel painful. But even moderately loud sound — such as busy street traffic — can cause harm if we hear it for hours.

Today, about one in every eight kids and teens have permanent hearing damage from being exposed to too much noise, says the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To avoid hearing loss, research suggests, kids shouldn’t be exposed to sounds louder than 75 decibels. That’s about as loud as a vacuum cleaner.

But there’s more to how we experience sound than just the decibel levels reaching our ears. New research is exploring how the brain makes sense of what we hear — and why some sounds feel unpleasant, even when they’re not dangerously loud.

Noise and the brain

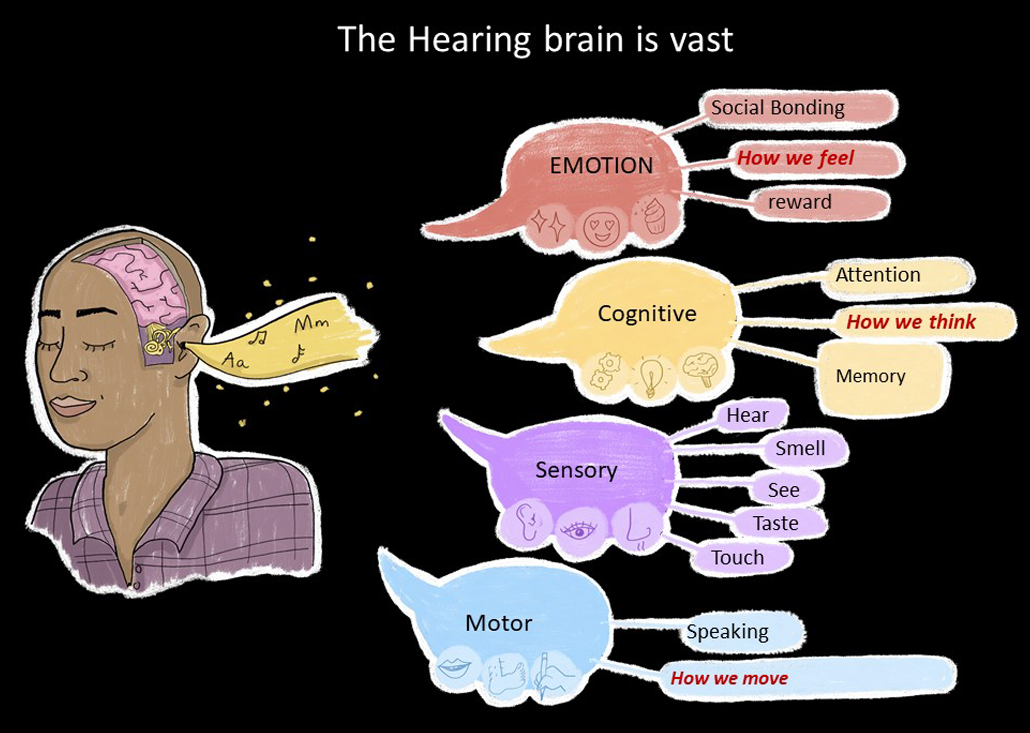

“Our ears capture sound, but we hear with our brains,” explains Wei Sun. He’s an audiology researcher at the University at Buffalo in New York. The auditory nerve relays sound signals from the ears to our brain. Nerve cells in the brain then process that input by sending each other electrical signals. That electrical activity gives rise to what we experience as sound.

Nina Kraus is among researchers taking a close look at this brain activity. An auditory neuroscientist, she works at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. Kraus also wrote the book Of Sound Mind: How our Brain Constructs a Meaningful Sonic World.

For their studies, Kraus and her colleagues placed caps embedded with electrodes on people’s heads. Those caps pick up brain activity as the ears detect sound. In this way, researchers were able to map parts of the brain involved in listening to and interpreting sounds. Those regions include ones that play a role in thinking, moving, feeling and sensing.

“There’s a lot that goes on in the brain when processing a sound,” notes Laurie Heller. “You’re deciding whether or not you like the sound, whether to pay attention to or ignore the sound, what to do with that information.”

Heller is a psychologist who studies how the brain interprets sound. She works at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pa. Her work has explored why some sounds register as unpleasant noise. For instance, a bubbling brook might feel like a peaceful sound — even when it’s as loud as an air conditioner that seems like an annoying racket.

In one experiment, her team used a sound effect called a vocoder. It slightly changed some of the properties of common sounds. Then the team asked people to guess the source of each tweaked sound. Listeners also rated how they felt about it. Some sounds were pleasant, such as a flowing stream. Others were unpleasant, like a drink being slurped.

It appears that how people feel about a sound can depend on what they think caused it, Heller says. When people misidentified a neutral sound as having a negative source, they rated it as less pleasant. For example, the sound of a sink draining is neutral. But people rated it unpleasant or even disgusting when they thought it was the sound of someone slurping a drink. Meanwhile, people felt better about sounds they thought came from a neutral or positive source.

“Feeling negatively about the event that caused the sound is the most important predictor of its unpleasantness,” Heller finds.

People with hearing loss may have a harder time identifying the true cause of a sound. And that could put them at higher risk of judging what they hear as unpleasant.

Heller also works with people who have a condition known as misophonia (Mee-zoh-FOH-nee-uh). It can make people feel angry or distressed when they hear common sounds — ones that others may not even notice (such as someone chewing or breathing). Studying their brains may offer insight into why any of us experience some things as noise, Heller says.

Annoying, or OK?

In a recent experiment, when people thought the sound of scraping utensils was the chirping of birds, they felt less annoyed by the sound. Try this for yourself. First, watch the video with your eyes open. When you can see that the noise is being created by two utensils scraping against each other, does the noise feel pleasant or unpleasant?

VIDEO: LAURIE HELLER

Now, replay the video and listen with your eyes closed. Imagine those high-pitched little sounds are instead coming from birds. Does that make you feel any better about the sound?

Misophonia appears to arise from how some brains interpret sounds. In affected people, certain sounds trigger a lot more activity in a part of the brain that alerts us to important things. That region also engages our emotions.

This leaves these folks “paying a lot more attention to sounds they find unbearable,” Heller says.

Better understanding this mental connection could not only lead to new treatments for misophonia, but also tell us more about how the brain processes sound in all of us. That’s key, because other research is revealing that exposure to too much unwanted sound — what we define as noise — can harm the brain in several ways.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Mental impacts of noise

Noise, whether unpleasant or just too loud, can be stressful and distracting.

The brain constantly filters through lots of sensory inputs from the environment as it learns what it needs to be able to perform various tasks. Noise can make this harder, says Kraus. “Think of noise,” she explains, “as static that gets in the way of what the announcer is saying.” Dealing with that static can tire the brain.

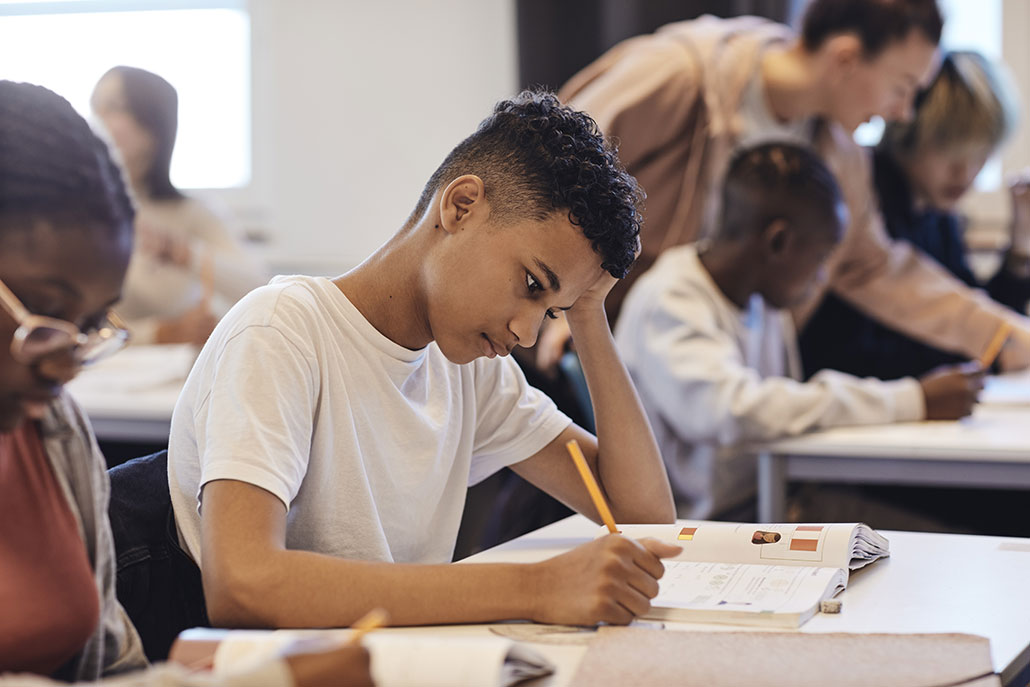

It’s well-known that noise can be a problem for learning. Over the past few decades, studies have shown that kids in noisy classrooms find it harder to focus. They also can have a harder time reading, remembering things or doing well on tests. Why? Their brains must work harder to make sense of information against a background of noise, says Kraus. That noise might be other kids’ chatter. It may even be outdoor traffic.

For instance, one 2005 study found that middle schoolers could understand only 71 percent of their teacher’s instructions when background noise levels were around 65 to 70 decibels. That’s just slightly louder than normal talking.

Noise around 70 decibels could impact reading comprehension as well, a 2019 study found. When kids in middle or high school were asked to read and answer questions about science passages, those in noisy classrooms attempted fewer questions. They also got more answers wrong than did those in a quiet classroom.

Noisy classrooms may be a common problem. In many U.S. schools, kids with normal hearing can understand only 75 percent of the words read from a list, according to the Acoustical Society of America.

Noise doesn’t just affect our attention while we’re listening to it. Kids exposed to a lot of noise also develop “noisier brains,” says Kraus. By that, she means that their auditory nerves stay active even when the surroundings are quiet.

That ongoing activity looks like static in the brain, says Kraus. And such static can make it hard to focus on what we want to hear.

Kraus learned this several years ago. She was part of a team that recorded brain activity in ninth graders who were watching a movie. At the time, disruptive sounds played in the background. Kids who grew up in noisier environments had noisier brains overall. And as they watched the movie, parts of the brain that make sense of speech were less active. That could make it harder to tune out that noise and focus on the movie’s dialogue.

There may be ways to help “turn down” that background noise in the brain. For instance, Kraus found that student athletes at her university had very quiet brains. That is, there was less static — or background brain activity — compared to non-athletes. Plus, the athletes’ brains were more responsive to sounds. That could help them focus on auditory signals without noise getting in the way.

Why might playing sports help reduce the brain’s background noise? When you play a team sport, you have to tune in to certain sounds: your coach’s voice, a teammate running or even the sound of your own breathing, Kraus explains. Perhaps this type of focus trains the brain to make better sense of meaningful sounds, such as speech, even in areas where noise abounds.

Impacts beyond the brain

Stress caused by noise can impact more than just the brain. “Hearing is our alarm sense,” says Kraus. It triggers a stress response, often called fight or flight. That response can help protect us from danger. But it can be bad when what triggers the stress response doesn’t go away.

“Constant noise can cause us to live with a low level of alarm and anxiety,” explains Kraus.

Omar Hahad studies how noise-triggered stress can cause harm. He works at the medical center at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, in Germany. “Mental stress is a risk factor for many diseases,” he points out. That includes anxiety, depression and headaches. It also includes heart disease and even digestive problems.

Nighttime traffic noise may be linked to cardiovascular problems, Hahad and his co-workers reported last November. As volunteers slept one night, they listened to recordings of car, train and airplane noise. Another night, they had a quiet night’s sleep. As they slumbered, small machines strapped to their arms recorded pulse rates and blood pressure. The next morning, each person got blood tests and answered questions about how well they had slept.

Their blood vessels showed more signs of stress after a night of traffic noise. Blood pressure was also higher after the noisy sleep — and the recruits said they had slept worse. Nighttime noise played a role in these poor outcomes, Hahad’s group now suspects.

Annoying noise can raise the body’s production of stress hormones, too, Hahad notes. In the short term, those chemicals (such as cortisol or adrenaline) help aid the fight-or-flight response. But those hormone levels should not remain high, he says. If they do, they can damage blood vessels and other tissues. Over time, that damage may lead to heart disease and diabetes. (Noise tends to lead to poorer sleep among children, too, lowering overall health. That’s according to an October 2023 report by the American Academy of Pediatrics.)

Exposure to noise only raises each person’s risk of disease a little, Hahad says. But if this happens to enough people across society, it may tip the balance for many of them, leading to more disease.

What you can do

Ear protectors can help limit hearing loss when the sounds around you get too loud. Pop in a pair of silicone or foam ear plugs if you’re mowing the lawn, riding the subway, going to a concert or doing something noisy, suggests Sherilyn Adler. She directs Ear Peace: Save Your Hearing Foundation. It’s in Miami, Fla. “I carry mine in my purse,” she says, “and even wear them at the gym or a noisy restaurant.“

Ear protection is especially important for musicians, Adler adds. By age 25, nearly half of musicians experience some level of noise-induced hearing loss. That’s according to the American Academy of Audiology. Special ear plugs can allow music to sound as it normally would, just at quieter levels.

If you’re listening to music through earbuds or headphones, turn it down, Balk recommends. “If you’re wearing ear pods and someone else can hear your music, that means it’s too loud,” she says. “If your mom is sitting next to you at arm’s length, you should be able to have a normal conversation with her [even with headphones on] without shouting.”

Plus, turn off any noises you know might distract you, says Kraus. That includes text notifications on your phone.

Protecting against certain other noises can be trickier. You can’t control when your neighbor decides to mow their lawn or where a construction crew will leave its trucks idling. Government policies that protect people from noise can help, says Kraus. Her town of Evanston recently banned the use of noisy gas-powered leaf blowers. (Electric ones are quieter.)

Having good coping strategies can help deal with feeling stressed out by noise, says Hahad. “Exercising regularly is a great way to reduce stress.”

All these tactics can help you make the most of the soundscape around you. “At best, sound connects us,” says Kraus. “But we also need to be aware of the ways it can disconnect us.”