Obesity makes taste buds disappear — in mice, anyway

Inflammation linked to their excessive weight caused the animals to lose one-fourth of their taste receptors

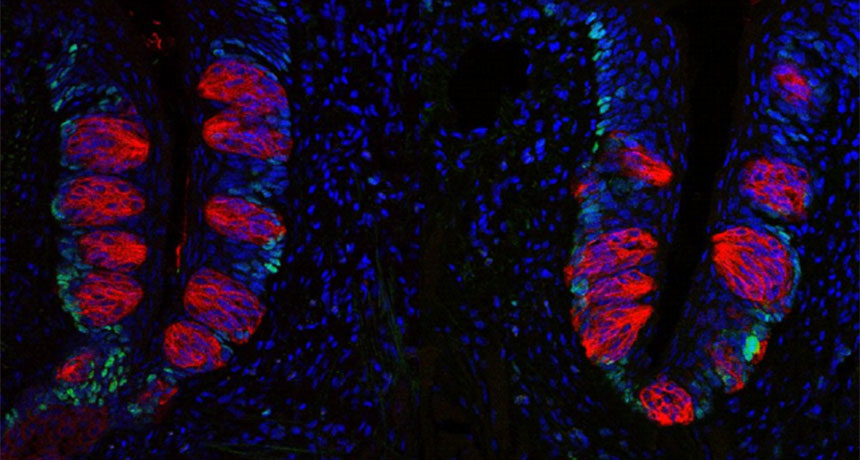

Mice that plumped out on a high-fat diet (right) lost a quarter of their taste buds (stained red). Compared to healthy-weight mice, they also had fewer of the kind of cells (stained green) that generate new taste buds.

A. Kaufman et al/PLOS Biology 2018

Mice that chowed down on too many calories gained weight. In another sense, these plump animals became big losers: One in every four of their taste buds disappeared. The findings come from a new study of animals on a high-fat diet.

A taste bud is a collection of 50 to 100 cells. Found on the surface of the tongue, these cells sense whether a food is sweet, sour, bitter, salty or umami (savory). Taste bud cells help identify safe and nourishing food. Some also turn on reward centers in the brain.

Each bud lasts only about 10 days. So the tongue must constantly make new ones. Special progenitor (Pro-GEN-ih-tur) cells will give rise to the replacement taste buds.

Studies had suggested that a sense of taste can dull in people with obesity. Scientists don’t know why this might happen. But if taste does weaken, “then maybe you don’t get the positive feeling that you should [from eating],” says biologist Robin Dando. He works at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. There, he’s been using animals to probe the biology of taste.

His team’s new study is looking into whether a diminished sense of taste might explain some overeating. People might find less satisfaction in a healthy portion of food.

The issue is an important one. Nearly one in five U.S. children and teens are overweight to the point of obesity. Heart disease, diabetes and cancer are among health problems that have been linked with being so seriously overweight.

For one new study, Dando’s group compared two groups of mice from the same litter (group of siblings). Over eight weeks, one group ate normal mouse food. At the end, their weight was in a healthy range. In addition, their tongues hosted a normal number of taste buds. The other animals ate only high-fat meals. During the trial they quickly plumped up — and lost about one-fourth of their taste buds.

The researchers described their findings March 20 in PLOS Biology.

The inflammatory findings

Cells in the taste buds of obese mice died off faster than they did in healthy-weight mice, the study showed. At the same time, the obese mice made fewer new cells to take their place.

Inflammation is a process in which the body makes immune cells, proteins and other materials in response to injury or infection — or obesity. It can cause redness, pain and swelling. Inflammation usually goes away once the body has healed or fought off an infection. But obesity tends to be a chronic condition. Not surprisingly, many studies in humans and other animals have shown that obesity seems to trigger persistent, low-level inflammation (In-fluh-MAY-shun). And it can occur throughout the body.

Brief bouts of inflammation can be helpful. They can kill off germs and sick cells. If inflammation persists, however, it risks harming healthy cells. Such nonstop inflammation now appears to underlie the loss of taste buds.

Taste buds in the obese mice had excess levels of a type of protein known as a cytokine (SY-toh-kyne), the researchers found. This cytokine regulates inflammation. Called tumor necrosis (Neh-KRO-sis) factor alpha, this protein also seems to damage taste buds, the researchers report.

They figured this out by running two different tests. In one, they investigated what happens in obese mice that can’t make the protein. And numbers of taste buds in them never dropped.

In the second test, they fed high-fat food to mice given genes that would not let their bodies gain extra weight. Because these mice never became obese, they never developed the inflammation linked to obesity. These mice, too, had a normal number of taste buds.

Taken together, these data suggest the fat mice lost their taste buds due to obesity-linked inflammation.

The take-home message

Indeed, that conclusion “provides a possible link between obesity and taste,” says Kathryn Medler. She works at the University at Buffalo in New York and was not involved with the new study. But she knows much about the subject. She’s a physiologist who studies how taste works.

Along with learning more about how inflammation damages taste buds, Dando is interested in looking for new treatments for obesity. One approach might be to restore the diminished sense of taste. “These mice lose taste buds,” he says. “Can we bring them back?”