Out in the cold

With pollution, over-fishing, and shrinking habitats, the life of a penguin isn't getting any easier.

By Emily Sohn

There’s a scene in the movie March of the Penguins in which a group of mother penguins leaves their chicks alone for the first time. The moms will be gone for days. As they waddle away, some of the fuzzy newborns hop after them, screeching and flapping their little wings. Driven by their need for food, the mothers don’t even look back.

|

|

Mother penguins and their chicks, as seen in the movie March of the Penguins.

|

| Jérôme Maison. © 2005 Bonne Pioche Productions/Alliance de Production Cinématographique |

“For some, this is not acceptable,” says narrator Morgan Freeman, describing the chicks’ reactions. “But it is nonnegotiable.”

In another scene, a penguin mother stands over her dead chick and wails at the sky. “The loss is unbearable,” Freeman explains.

In yet another scene, Freeman describes typical penguin behavior. “They’re not that different from us, really,” he says. “They pout. They bellow. They strut. And occasionally, they engage in contact sports.”

Such statements have drawn criticism from some biologists who say it’s wrong to attribute human feelings to animals. Penguin researcher Dee Boersma, however, says that this kind of anthropomorphism is a good thing.

“I think these movies are a wonderful opportunity to engage children and adults in the wonders of nature instead of the wonders of shoot-’em-ups,” Boersma says. She’s a conservation biologist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Hard life

Inspiring people to care about penguins is important, Boersma says, because life isn’t getting any easier for the quirky-looking birds.

Penguins live on land, on ice, and in the oceans of the southern hemisphere, but global climate warming is shrinking their habitats (see “Shrinking Glaciers“). Oil slicks and other types of pollution are making them sick. More and more often, fishermen are catching penguins in their nets by mistake. And over-fishing is making it harder for the animals to find fish to eat.

|

|

Emperor penguins travel long distances each year to reach their breeding grounds.

|

| Jérôme Maison. © 2005 Bonne Pioche Productions/Alliance de Production Cinématographique |

Penguins are especially sensitive to changes in the environment because they travel long distances during their lives, but can’t fly. Environmental damage along any part of their routes can have harmful effects.

The Emperor penguins featured in March of the Penguins, for instance, walk and slide on their tummies over ice for 70 miles each year to meet at the same breeding grounds. Similarly, Magellanic penguins, which live in South America, sometimes travel more than 2,000 round-trip miles between Argentina and Brazil.

Penguins gather in huge groups when they breed, which makes it easy for scientists to see if populations are declining.

|

|

Penguins gather in large groups when they breed.

|

| Jérôme Maison. © 2005 Bonne Pioche Productions/Alliance de Production Cinématographique |

“We’re interested in using penguins as sentinels of the environment,” Boersma says. In other words, if penguins show signs of distress, that’s a sign that the environment is experiencing stress, too.

Cool birds

Boersma has been studying Magellanic penguins in the Patagonia region of Argentina for 22 years. Every year, she spends September through March at a protected reserve called Punta Tombo, which borders the Atlantic Ocean. About 200,000 breeding pairs of penguins live there.

“It’s a megalopolis of penguins,” Boersma says. “It’s like New York City.”

|

|

Biologist Dee Boersma poses with a host of penguins.

|

| Courtesy of Dee Boersma |

Even so, she says, there are 20 percent fewer penguins living at Punta Tombo now than when she started working there in 1987.

Boersma has big goals when it comes to penguin research. She wants to learn everything there is to know about penguins. To that end, she and her colleagues tag birds every year and track their migration routes with satellite technology.

The researchers also visit nests and count how many penguins return from year to year. They spend hours observing the animals every day, trying to figure out how penguins choose their mates, why they make certain noises, how oil spills affect populations, and how Punta Tombo’s 70,000 yearly human visitors affect the behavior of the birds and their ability to reproduce successfully.

“What’s mostly driving us,” Boersma says, “is to make sure penguins are going to be here for future generations.”

Penguin personalities

Studying penguins is as entertaining as it is interesting, Boersma says. “I don’t know anyone who won’t say they like penguins,” she says. “They are fun to watch. They’re comical. They walk upright. What’s not to like?”

Now that she has known some of the penguins at Punta Tombo for more than 2 decades, she has grown to appreciate their personalities. “Some are nervous,” she says. “Some are placid.”

One of her favorites is a 21-year-old male who makes a grunting “hmmph” sound every time the researchers pick him up to weigh and measure him.

|

|

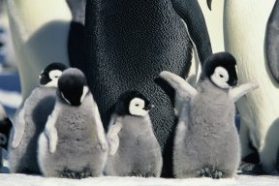

Emperor penguin chicks.

|

| Jérôme Maison. © 2005 Bonne Pioche Productions/Alliance de Production Cinématographique |

I never realized how amazing penguins are until I saw March of the Penguins. The birds go to incredible lengths, I learned, to find food for themselves and their babies. In the Antarctic, they withstand brutal snowstorms and frigid temperatures, and they go for months without food, all for the sake of their chicks.

The film also gave me an appreciation for how cute baby penguins are. Afterwards, all I wanted to do was to adopt a group of the adorable puffballs and protect them from winds, cold weather, and hungry predators.

On second thought, though, that would probably be a bad idea. People may have something in common with penguins, but penguins would probably be too noisy and wild to make good roommates. My cat, by the way, agrees.

Going Deeper: