Pacific garbage patch may be 16 times bigger than thought

Fishing nets and ropes make up roughly half of the debris

Fishing nets and ropes make up nearly half of the mass of plastic in the Pacific Ocean’s notorious garbage patch, a new study suggests.

NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Program/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

We’re going to need a bigger trash can.

There is a pooling of plastic waste that floats in the ocean between California and Hawaii. It’s known as the “great Pacific garbage patch.” This garbage patch spreads over 1.6 million square kilometers (600,000 square miles), a new study finds. And it contains at least 79,000 tons of material. That’s the equivalent to the mass of more than 6,500 school buses. The new numbers mean the hoard is four to 16 times as massive as past estimates had suggested.

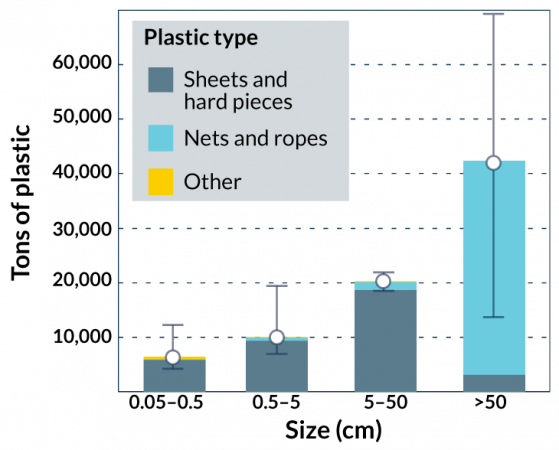

Its name might imply a huge floating island of junk. This garbage patch is something else. It’s an area of the ocean where pieces of plastic can be found in high concentration. About 1.8 trillion plastic pieces make up the great Pacific garbage patch, scientists estimate. About 94 percent of the pieces are microplastics. These are particles smaller than half a centimeter (0.2 inch). Because they are so tiny, they make up only 8 percent of the overall mass. Large pieces, 5 to 50 centimeters (2 to 20 inches), account for 25 percent of the mass. Extra-large bits, those bigger than 50 centimeters (20 inches), make up the most of the mass: 53 percent.

Story continues below graph.

Humans’ ocean activities, such as fishing and shipping, shed much of this plastic, the researchers found. Discarded fishing nets, for example, make up almost half of the garbage patch’s mass. A lot of that litter contains especially durable types of plastic. These include polyethylene (PAA-lee-ETH-uh-leen) and polypropylene (PAA-lee-PRO-pu-leen). Such plastics are designed to survive in aquatic environments.

Laurent Lebreton is an oceanographer with Ocean Cleanup. That’s a nonprofit foundation in Delft, the Netherlands. To get the new size and mass estimates, Lebreton and his colleagues collected plastic samples from the ocean surface and took images from above. They also used a computer to model particle pathways based on ocean circulation patterns and what’s known about where the plastic entered the ocean. The team published its findings March 22 in Scientific Reports.

Aerial photos provided the best tallies of the larger plastic pieces, the researchers note. That might explain why the new estimates are so much higher. Those older ones had relied on images taken from boats and data on ocean trawling — in addition to estimates from computer models.

But there’s also another potential explanation: The patch could have grown. It may have received a huge increase of debris from the 2011 tsunami that hit Japan and washed trash out to sea.