Common parasite may help mussels survive heat waves

By whitening shells, the organism helps the shellfish stay cool on sunny days

A common parasite that whitens the shells of mussels may actually help them survive heat waves, a new study suggests

Gary Kavanagh/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Sid Perkins

When is a parasite not a parasite? Answer: When it provides a benefit to its host. Consider some microbes long thought to bring only harm to coastal mussels. New research shows some may actually help their hosts survive dangerous heat waves.

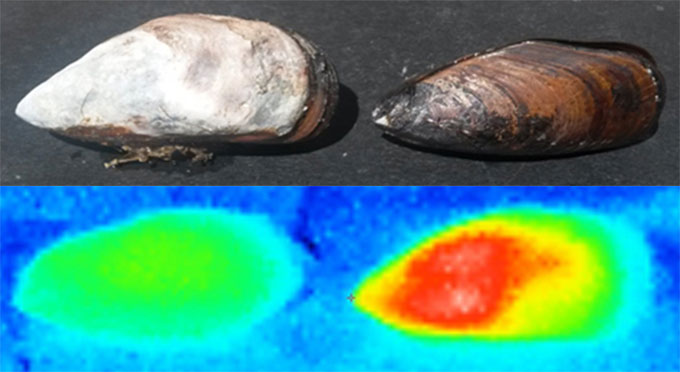

Called cyanobacteria (Sy-AN-oh-bak-TEER-ee-uh), these bacteria bore into the mussels’ outer shells. Studies had shown this can weaken mussel shells, notes Katy Nicastro. She’s a marine biologist at Rhodes University in South Africa. Being infested with those microbes can slow a mussel’s growth — and reproduction, too. It can even cause the shells to shed their dark outer coat. But lighter-colored shells absorb less sunlight. And that might keep their hosts from overheating on sunny days.

Nicastro and her teammates wanted to know just how much heat protection those microbes might offer. So they collected mussels in Europe. They retrieved them from a rocky shore in northern Portugal. Some mussels had shells infested with the microbes. These had large white patches. Non-infested mussels had normal dark shells.

The researchers first removed the mussels from their shells. Then they inserted temperature sensors inside those shells. They placed these “robomussels” at nine coastal sites across Europe. The most northerly sites were in the Orkney Islands, north of Scotland. The most southerly sites were in Portugal.

Up to a dozen robomussels were glued next to live mussels on rocks in the intertidal zone. Here, seawater would cover the shells at high tide. Low tide would expose them to the air and sun. The sensors showed the temperature could drop 8 degrees Celsius (14.4 degrees Fahrenheit) or more when the shells were submerged.

Those sensors took measurements every half hour from August 1 to September 13, 2017. In the end, the researchers had to ignore data from three sites where weather records were not available.

Trends for the other six sites were clear. When not underwater, dark-shelled robomussels warmed faster. Sensors inside the dark-shelled robomussels also reached a higher temperature than the lighter-shelled ones. The team described its work in the June Global Change Biology.

These data suggested shell color could mean the difference between life and death for mussels. So for these microbe infestations, Nicastro says, “Now we have to consider the balance between positive and negative effects.” It appeared those microbes can sometimes help the mussels.

To test that, Nicastro’s team looked at death rates for mussels during three 2018 heat waves in France. More than 95 percent of the mussels dying during the heat waves had dark shells, studies showed. Dark-shelled mussels were likely between 1.67 and 4.77 °C (3 and 8.6 °F) warmer than those with lighter shells. This suggests light-shelled mussels were more likely to survive.

Shell-weakening microbes usually are not viewed as a good thing for mussels, says Christopher Harley. He’s a marine biologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. “But during heat emergencies, that can save [a mussel’s] life,” he says.

Mussels may not seem to be important creatures, but they are, says Harley. At low tide, intertidal mussel beds provide a moist, cool habitat. Hundreds of different species live among them. This includes everything from hermit crabs and worms to sponges and sea cucumbers. Indeed, Harley says, “Mussel beds are the apartment complex of the rocky shore.”