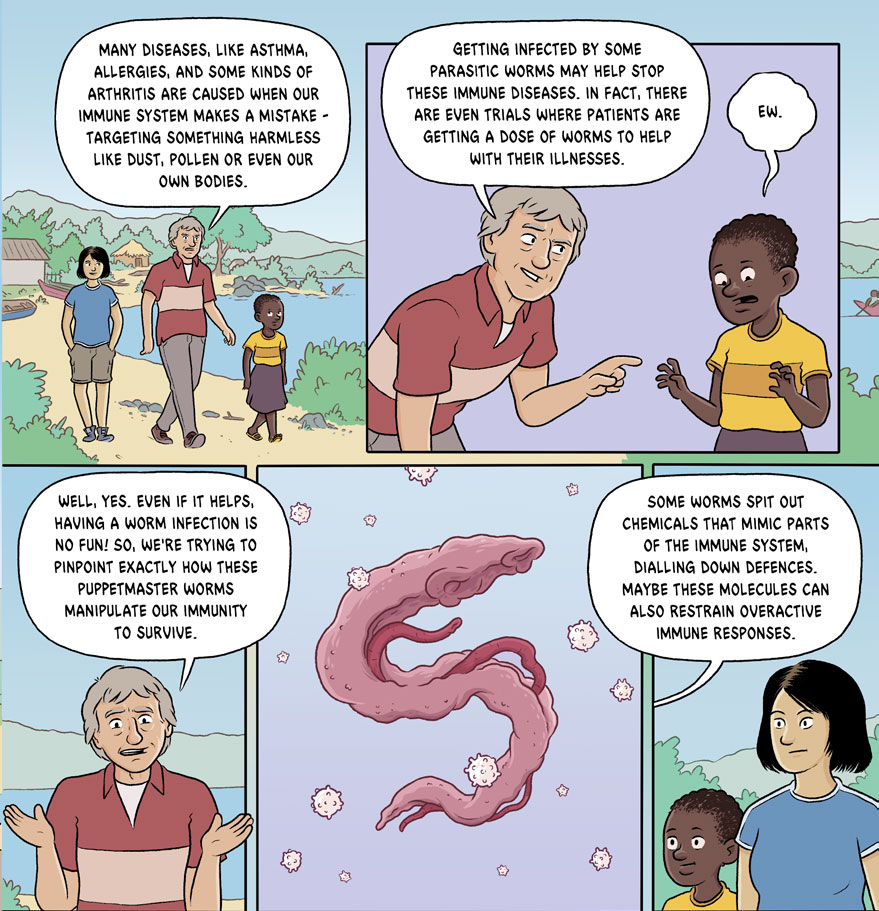

How wriggling, blood-eating parasitic worms alter the body

Though they make many people sick, these worms could lead to — or become — new medicines

Terrifying much? This tapeworm and many kinds of parasitic worms have spikes and suckers on their heads. They use these to attach themselves to the inside of their host’s gut.

selvanegra/iStock/Getty Images Plus

A few years ago, Alex Loukas let 40 hookworms burrow into his skin and live inside his body. “I’ve still got them,” he says.

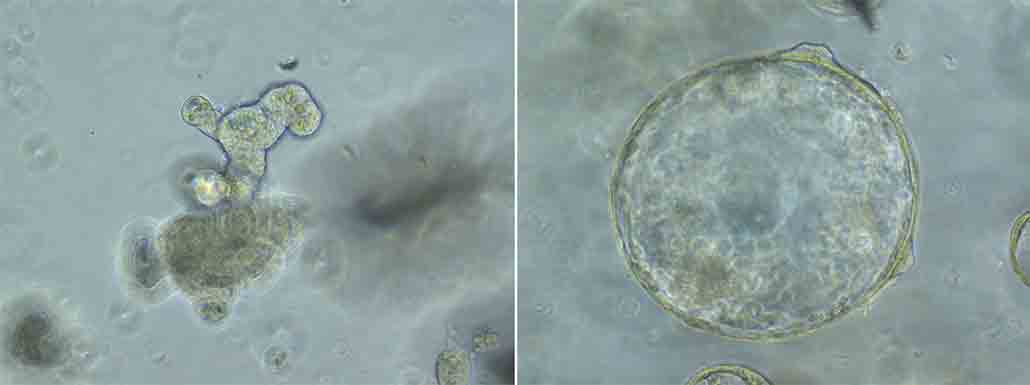

Hookworms are parasites. The type Loukas has is named Necator americanus. In the wild, this hookworm hatches in soil. Each starts out as a larva that is too tiny for your eye to see. It usually gets into someone’s body through their foot. But Loukas was infected very carefully, in a lab. With the help of a microscope, his colleagues put exactly 40 larvae into a drop of water on his forearm. Then they put a bandage over the top. “It doesn’t hurt, but gets intensely itchy,” he says. He had to resist scratching to let the larvae wriggle in through the skin.

Once in his body, those larvae made their way to his gut and grew up. Adults are a bit longer than a grain of rice. “They live in the gut and suck blood, like an internal leech or mosquito,” says Loukas. They also mate and lay eggs, which exit the body when Loukas poops.

Why in the world would Loukas go through all of this? It’s for his work. He’s a medical researcher at the Cairns campus of James Cook University in Australia. His team studies how parasitic worms affect the human body. In this research, people volunteer to get carefully controlled infections. Loukas decided that if he was going to ask others to infect themselves, he should probably try it, too.

Infections of more than 100 hookworms can be very harmful. One in every four people on Earth host these or some other type of parasitic worms. These infections can cause great pain and suffering. However, a small, controlled worm infection can be safe. The type of hookworm infecting Loukas can live in his body for many years, but its eggs can’t hatch there. They must hatch in soil. So as long as he stays away from infected soil, he will never host more than 40 worms. “I have no symptoms,” says Loukas. The worms may even benefit his body.

Parasitic worms, also called helminths, remodel the human body to their liking, notes Rick Maizels. He studies parasites and the immune system in Scotland at the University of Glasgow. Worms don’t want the body to eject them. So they tend to calm the immune system, he says.

Many disorders involve an overactive immune system. Examples include diabetes, heart disease, allergies and asthma. If small numbers of worms can calm the immune system, then might the good outweigh the bad (and the ugly) for some people?

This is what Loukas is trying to learn. People might not even need to get infected to take advantage of worms’ abilities. Researchers are also studying substances the worms make that alter the immune system. They hope to turn that stuff into new, non-wormy, medicines. In the future, nightmarish parasitic worms may lead to new treatments. They may also lead to vaccines against worms to help people who now suffer from these parasites.

Worms at work

To infect volunteers and run other experiments, Loukas and his team need fresh larvae. Several team members harbor worms. When they go to the bathroom, they collect samples of their feces. An “unfortunate guy” in the lab gets to look through the poop for worm eggs, says Loukas. A single female hookworm releases 10,000 to 15,000 eggs per day, he says. The team then hatches and raises the larvae until they’re ready for research.

Loukas and his colleague Paul Giacomin, who’s also at James Cook University, recently finished running a clinical trial. They investigated whether a hookworm infection can help prevent diabetes. That’s a disease that happens when the body can’t process sugar correctly.

The team recruited volunteers who were overweight and whose bodies weren’t doing a very good job using sugar released from food into their blood. None yet had diabetes, but all were “almost certainly” going to develop this disease within a year or two, Loukas said. Could hookworms stop that from happening?

The team divided the volunteers into three groups. One group got 20 hookworms. Another group got 40. A final group got a dollop of spicy hot sauce on their arms. That was a placebo, or a pretend treatment. It has the feel of the real one but without any medical effect. To mimic larvae burrowing through the skin, “it was supposed to create an itching sensation,” Loukas explains. That way none of the volunteers or researchers would know who had worms and who didn’t.

For two years, the team monitored the volunteers. They watched for any negative symptoms from having worms. They also checked the volunteers’ risk for diabetes. The hope is that this risk would fall in those infected with the worms. The results are not yet published. But Loukas says they look promising.

At the end of the trial, the team offered the volunteers a drug that kills worms. Most of them chose not to take it. “They want to keep their worms,” says Loukas. “They often refer to them as their family.”

This trial was small. There were only around 50 volunteers. Since the 2000s, researchers have run quite a few trials investigating whether worms could treat various human ails involving the immune system. Small trials have shown promise, but larger ones have had disappointing results.

Loukas says his approach is different. Many of those trials used a type of worm that evolved to infect pigs, not people. The body quickly ejects these worms. He thinks worms have to stick around and “get nice and large” to have a helpful effect.

Keeping things calm

If hookworms really can help prevent diabetes, the next step is to figure out how they do it. Scientists don’t yet have all the answers to how worms calm the immune system. But they’ve discovered some amazing things.

Maizels and his team found that parasitic worms increase numbers of a certain type of immune cell. It’s called a regulatory T-cell, or T-Reg for short. “They’re like the police officers of the immune system,” says Maizels. They keep things calm so that the body doesn’t react too strongly to foods, pollen and other harmless bits of the environment.

The really exciting thing about T-Regs, though, is that they lower inflammation. Inflamed tissue tends to get red and swollen. That’s because the body has sent extra blood to this area that is enriched with immune cells. These immune cells fight off infection. But they can damage healthy cells in the process. Sometimes, inflammation happens even where there is no infection to fight. This is one of the root causes of a huge number of diseases, including diabetes and heart disease.

Loukas and his team want to be able to treat inflammation without needing to infect anyone. So they’re trying to mimic whatever it is the worms do to increase T-Regs. The team collects the substances hookworms give off as they feed. “Many people call it worm spit or worm vomit,” he says. They find proteins in the stuff and study them. One protein they found increases the number of T-Regs in mice and in human cells they’ve studied in the lab. Someday, it could lead to new therapies for diseases that involve too much inflammation. Loukas founded a company, Macrobiome Therapeutics, which is working to develop such treatments.

Weep and sweep

Many types of parasitic worms set up house in the human gut. Their antics here also have the potential to lead to new types of treatments. To get rid of worms, the gut does something called a “weep and sweep,” explains Oyebola Oyesola. She studies parasites and the immune system at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. The “weep” part involves squirting out mucus. This slippery stuff makes it tough for worms to hang onto the walls of the gut. The gut also “sweeps” them away with extra water and runny diarrhea. “I know this is gross,” says Oyesola, but it’s also “pretty cool.”

Some worms may have found a way to avoid getting swept away. Oyesola is part of a team that last year found a certain protein on some gut cells that helps control the weep-and-sweep response. It works a bit like an “off” switch. The body’s immune system likely uses this protein to avoid runaway inflammation. When her team took the protein away from mice, their bodies couldn’t turn off the weep and sweep. So this response was strong. The mouse bodies did a better job than usual of clearing worms.

Worms may have hacked this system. Some worms produce a substance that triggers the weep-and-sweep “off” switch.

Maizels has found that worms can do even more to remodel the gut. The stuff they spit out can change what types of new cells grow there. And the gut grows rapidly. It grows a completely new surface every few days.

Their team grew miniature guts from mouse cells in the lab. They added worm spit to some of these guts as they were growing. Guts that grew normally made lots of different cells — including ones that squirt out mucus to expel worms.

Guts treated with worm spit grew larger and faster but contained just one type of cell. These guts couldn’t spit out mucus. In addition, their rapid growth would likely help repair any damage the worms might cause as they tunnel around. Both changes would allow the worms to survive longer in the gut.

The fact that worms seem to be able to repair gut damage could lead to new therapies for people who have diseases that cause similar damage, suggests Maizels.

And worms aren’t the only creepy-crawly things that like to live inside the gut. The microbiome is a name for the community of all microscopic critters — mainly bacteria — that live inside us. Which bacteria colonize our gut can impact our health. In general, the more different types, the better. Worm infections tend to change which bacteria call the gut home. Some of these changes can be harmful. But in other cases, they might offer benefits. One 2016 study found that a worm infection could protect mice from an inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease). The worm infection made it harder for disease-causing bacteria to thrive.

Worm damage

Overall, parasitic worms appear to cause far more disease than they cure. In many parts of the world, parasitic worms infest the water or soil that people encounter on a daily basis. People get infected again and again. When not controlled, these infections can prove extremely harmful. Deaths from worm infections are rare, but these critters sicken and disable hundreds of millions of people each year. Most of these people are poor; many are children and pregnant women.

Parasitic worms stunt growth. They also can cause brain damage or delays in development, notes Peter Hotez. He is a pediatric scientist who develops vaccines at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. He’s spent his career bringing much-needed attention to the many problems that worm infections cause.

Often, a child with worms doesn’t look or feel sick. Yet if they don’t get treated, they likely won’t get enough nourishment and will not develop as well as an uninfected child. “These worms basically rob kids of their full potential,” says Hotez.

The U.S. Agency for International Development runs programs that bring de-worming drugs to more than a billion people each year, Hotez says. That helps. Still, vaccines against worms are also needed. “I call them anti-poverty vaccines,” says Hotez. Getting out of poverty is already hard. The health problems caused by worms make it even harder. But such vaccines are tough to develop. Why? A vaccine works by training the immune system to fight an infection. And worms are experts at evading the immune system. So even if someone’s immune system has the right training, the worms might prevent it from doing its job.

Despite this problem, Hotez’ team has developed a hookworm vaccine that is going through clinical trials. The vaccine trains the immune system to destroy two substances that hookworms need to survive. One of the substances helps the worms digest blood. Without this substance, they can’t feed themselves. They use the other substance to grow into their adult form. Without it, they can’t get large enough to attach to the gut.

Worm infections are found all over the world. But they are most common in tropical areas. Oyesola grew up in one of those places, Nigeria. “I’ve seen the impact first-hand,” she says. Her brother had worms as a child. The whole family took de-worming medicine afterward.

Oyesola also has seen what worms do to animals. Before she became a researcher, she worked as a veterinarian in Nigeria. “It’s pretty common to see worms in pets,” she says. That’s why pet owners are supposed to give cats and dogs medicine regularly to prevent worm diseases.

Parasitic worms pose the biggest problem in areas with a lack of access to clean water or clean toilets. The eggs of many parasitic worm species come out in feces or urine. If the eggs get flushed away, no problem. But if they sit on the ground or end up in bodies of water where people swim or wash, they may infect others.

Hopefully, someday, worm diseases will be a problem of the past. Then, perhaps, the worm benefits will begin to outweigh their harms. Developing new medicines is a slow process. It could be 10 years or longer before any worm-inspired treatments are ready. “However long it takes, we’ve got to keep going,” says Maizels.