Phoning in heartbeats

New device uses a smartphone to collect and email data on heart rhythms

SSP

By Sid Perkins

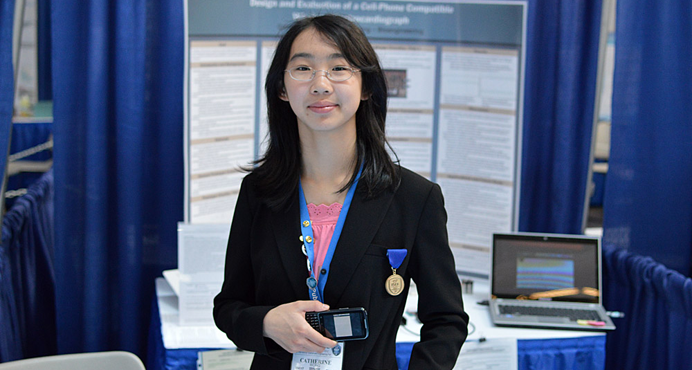

When a heart attack strikes, every moment counts. Yet victims must wait for doctors to diagnose the cause and the severity of the problem before they can prescribe or start any specific treatment. It soon, however, may be possible for data from a detailed heart exam to reach the hospital even before the patient arrives. It’s all thanks to a nifty piece of electronics designed by Catherine Wong, a 16-year-old 11th-grader atMorristownHigh School in Morristown,N.J.

When a heart beats, it triggers tiny electrical changes in a person’s skin. Cardiologists, doctors who specialize in problems affecting the human heart, often measure and record these changes by placing several dime-sized sticky patches onto a patient’s skin. Wires connect those patches to a recording machine. The test, which is used to measure how often heartbeats occur and how regular they are, is called an electrocardiogram. Doctors refer to this test as an EKG, after the abbreviation for the German name for this exam.

Because they require sophisticated equipment, EKGs are almost always performed in a doctor’s office, a clinic or a hospital. But Wong’s device means that anyone with a cell phone — doctors, nurses, paramedics or even a patient — could perform a simple version of the test almost anywhere.

The prototype that Wong built is a book-sized circuit board loaded with electronic components and wires. The device, which attaches to a standard sticky patch that doctors use for EKGs, records electrical changes caused by heartbeats and then sends those signals wirelessly to a cell phone. A separate program on the cell phone converts the signals into an image — the same image that an EKG machine in a hospital or clinic would create. The new device’s image then can be e-mailed to a doctor anywhere in the world.

An EKG performed in a hospital or a doctor’s office normally records data from several sites on a person’s chest at the same time. But because Wong’s device is wireless, a detailed EKG using her prototype might require moving a single sticky patch from place to place. That means a full picture of a patient’s condition might require taking a series of measurements rather than one single reading. Trying to use more than one wireless patch at a time to transmit data to the cell phone probably wouldn’t work, she notes.

Wong says that all of the circuitry on her prototype could be shrunk onto a single computer chip — something small enough to even fit into the dime-sized sticky patch. The high school inventor described her device May 17 at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Pittsburgh, Pa.This event is sponsored by Intel Foundation and run by the Society for Science & the Public (which publishes Science News for Kids).

Wong thinks her device would be useful in impoverished areas of developing nations that lack local healthcare services. But even in rural areas of industrial nations such as theUnited States, this novel device could allow patients timely access to a doctor when every minute can make a difference, she says.

This is one in a series of articles covering the Intel ISEF 2012 competition. Check back soon for more stories.