The plant world has some true speed demons

These wonders of the plant world evolved clever ways to fling, snap and burst — sometimes in the blink of an eye

The leaves of the Venus flytrap are snapping shut, jailing its prey through a process called snap-buckling. The outer leaf surface expands until it’s too much for the inner surface of the leaf to bear.

ESBEN_H/ISTOCKPHOTO

By Dan Garisto

Somewhere in the wetlands of South Carolina, a fly alights on a pink surface. As it explores the scenery, the fly unknowingly brushes a small hair. It’s sticking up from the surface like a slender sword. As the fly continues to stroll along, it grazes a second hair. All at once, the pink surface closes in from both sides. Two leaves have snapped shut like a huge pair of botanical jaws.

This blur of movement lasted only a tenth of a second. But this fly will never leave this death trap.

“We don’t think plants move,” says Joan Edwards. She’s a botanist at Williams College in Williamstown, Mass. Yet some plants, she notes, “can move so fast you can’t catch them with the naked eye.”

We tend to picture plants as largely unmoving — rooted in one place until they die. To describe something boring, we say it’s “like watching grass grow.” But such phrases offer a naïve view of the plant world.

All plants grow, a rather slow form of motion. Many also have the capacity to move rapidly. The snapping jaws of the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) are perhaps the most famous example. But they are far from the only one. Plants exhibit plenty of impressive actions. Consider the explosive sandbox tree (Hura crepitans). Also known as the dynamite tree, it can fling seeds the length of an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Sundews (genus Drosera) have sticky tendrils that curl around prey. And within seconds of being touched, the aptly named touch-me-not (Mimosa pudica) folds its compound leaves.

Plants have evolved a broad range of approaches to movement. It spans an equally huge spectrum in terms of speed. Roots crawl through the soil at only about 1 millimeter (0.04 inch) per hour. In contrast, some plants have found a way to shoot their seeds into the environment at speeds of tens of meters (more than 100 feet) per second.

The most dynamic plant movements have long captivated scientists.

Take Charles Darwin. Of all plants, he described the Venus flytrap as “one of the most wonderful in the world.”

In his 1875 book Insectivorous Plants, he described tests he conducted on this curiosity. He baited some with raw meat. He prodded others with objects as fine as human hairs. He even tested how the plants’ traps reacted to drops of chloroform. Darwin never fully unlocked the plant’s secrets. Still, he understood that the shape of its leaves played some role in how speedily they could trap prey.

Modern researchers can study rapid plant movements with a precision that Darwin would envy. A little more than a decade ago, scientists began using high-speed digital cameras and computer modeling to home in on plant motion. Frame-by-frame analyses, along with high-resolution lenses, at long last offered a detailed look at what gives plants their speed.

Emerging evidence now points to a surprising variety of mechanisms. Researchers have turned up contraptions that kick like a soccer player or throw like a lacrosse player. One plant even generates heat to explosively launch its seeds.

Nearly 150 years after Darwin’s work, what drives such research remains the same — a fascination with fast-action plants.

Story continues below video.

Putting the moves on

In the early 2000s, Yoël Forterre was a young scientist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. His adviser, another scientist, made him a gift of a Venus flytrap. The plant, new to him, amazed Forterre at its ability to move without muscles.

The scientist soon realized that its motion could be understood by thinking of it through his own specialty: soft matter physics. This field investigates how certain materials — such as liquids, foams and some biological tissues — can deform, or change shape.

Forterre published a study in 2005 that was among the first to rely on both high-speed cameras and computer modeling to study how speedy plants move.

High-speed digital cameras made such research possible, notes Dwight Whitaker. He’s an experimental physicist at Pomona College in Claremont, Calif. Around this time, cameras were making their way into university labs. “With film, you get one chance” to catch some fleeting action, he notes. Everything has to be arranged in advance. That’s why movie directors call out to their crews “lights, camera, action!” — and in that order.

A flytrap’s leaves face each other like two halves of a book. With super-fast cameras and computers, Forterre’s team could track the tiniest changes in the curve of those leaves. This allowed his group to see how the plant’s speed relied on the special shape of those leaves.

When a fly or other prey triggers the trap, cells on the green outer surfaces of the leaves expand. Cells on the pink inner surfaces don’t. This creates a tension that pushes the outer surface inward. Eventually, the pressure becomes too great. The leaves, originally convex in shape (bowing outward) now rapidly flip to concave (curving a bit inward like a bowl). This slams shut the trap in a process known as snap-buckling.

One way to understand this motion is to look at a popular child’s toy, says Zi Chen. An engineer at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., he has studied the flytrap. Rubber poppers are little rubber half spheres that can be inverted (turned inside out). Like a compressed spring, the inverted toys have a lot of stored energy, which is known as potential energy. As they snap back to their original shape, the poppers convert that stored energy into kinetic energy — the energy of motion. This can launch the toys several feet into the air.

Similarly, potential energy builds up as the outer surfaces a flytrap’s leaves press against the inner ones. But they can be near-instantly converted to kinetic energy. This is what slams shut the leafy trap within a tenth of a second or so.

Blast off!

Around the same time Forterre was studying flytraps, Edwards and her husband were leading a group of budding researchers at Lake Superior’s Isle Royale. They were scouting native plants.

As Edwards tells it, a student stuck her head down to sniff a flower of the bunchberry dogwood (Cornus canadensis). Suddenly, she noted, “something went poof.” Intrigued by this distraction, the team brought specimens back to the lab. They wanted to capture the behavior on video. But whatever triggered the dogwood poof wasn’t visible. So Edwards upgraded to a camera that could take 1,000 images per second.

“It was still blurry,” she recalls. “I thought something was wrong with the camera.”

She brought the problem to Whitaker, who was then at Williams College. He found the plant simply was moving too quickly for the camera to capture.

To stop the plant’s movements, Edwards ordered a faster camera. This special device — the best that was then available — could collect 10,000-frames-per-second. And for the first time, she could see the mechanism clearly.

Story continues below video.

Four petals are fused together. They barely hold down four bent, armlike structures — pollen-holding stamens — that protrude from the petals. When disturbed — by a fat bumblebee or the nose of an inquisitive human — the petals split apart. This frees the stamens, allowing them to flip outward. They move, accelerating to a g-force of 2,400 (which is 2,400 times the acceleration of Earth’s gravity). For comparison, fighter pilots can handle a g-force of about 9 before passing out.

The stamen’s flip shoots out a pollen sack (one had been attached to each stamen’s tip). A cloud of that pollen now flies into the wind or whatever else might have triggered the burst.

Edwards’ early work signaled the start of a now-flourishing research area. High-speed cameras and other high-tech equipment soon began finding use in probing the secrets of speedy plants.

Edwards and Whitaker, for example, discovered that, like a detonating nuclear bomb, a peat moss named Sphagnum affine explodes into a mushroom cloud. On dry sunny days, tiny bloated spore capsules that dot the surface of the moss can dry out. This causes them to shrink down. That increases the air pressure within the capsules to several times the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere. When that pressure becomes too great, the capsule will explode, spewing a cloud of spores.

Story continues below video.

The duo used computers to model what is happening. This helped to show, they reported in 2010, that the mushroom cloud shot the spores 20 times higher than they would otherwise have flown. That height greatly boosted the chance that those spores would catch a good breeze, from which they could migrate to a new patch of land.

Aquatic propulsion

Plants may even manage impressive motions underwater. Take some bladderworts (genus Utricularia).

Aquatic forms of this plant thrust their flowers up from thin leafy stalks below the surface of a lake or pond. The stalks are dotted with traps. Each is shaped like a sack with a hinged lid. Quite small, each sack is but a few millimeters (hundredths of an inch) in size.

To set a trap, the plant pumps out water from inside its sack. This inverts the sides like a pair of sucked-in cheeks. When prey, such as a mosquito larva, triggers hairs at the trap’s mouth, the lid opens. Water from outside gets sucked in, pulling in the prey. The larva then becomes trapped as the lid closes. From open to close, bladderworts can trap prey in about a thousandth of a second!

Story continues below image.

Water is, in fact, a key player in the most fundamental of plant movements: growth.

“Growth occurs when water moves into a cell and inflates it,” notes Wendy Kuhn Silk. She is a biologist at the University of California, Davis. “The speed of most growth responses is determined by the rate of water movement in a tissue.”

Water moving from cell to cell can push out branches and send a plant’s roots through the soil. It can even move leaves so that they face the sun. But such movements are far from lickety-split. For instance, if a Venus flytrap had to rely on water-driven motion, it might take a full 10 seconds to close. Even the most lethargic fly would hardly fall for such a slow-motion ambush.

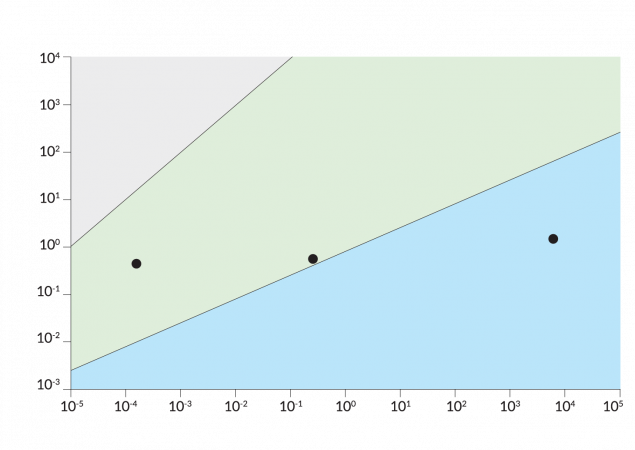

Story continues below graph.

Plants don’t become true action figures until they harness certain physical properties — what scientists refer to as mechanical instabilities. Sometimes these instabilities develop as a plant grows. Like the string of a bow pulled until taut, plants can store up potential energy. When a string is pulled too far, or nudged enough, it will now release that pent up energy. This transforms potential energy into the energy of motion. A similar snap into action can occur in plants.

For instance, mechanical instabilities give the flytrap its snap. They can even allow some plants to jump. Take the horsetail plant, Equisetum. It releases microscopic spores shaped like a bendy X. When wet, the legs of those spores curl up. As they later dry out, their legs uncurl. The curling and uncurling due to changes in humidity let the spores skitter around. Sometimes the legs compress. Later, when they release, they can exhibit a forceful kick that flicks some spores into the wind.

Story continues below video.

So many ways to move

The variety of action moves that plants can exhibit is proving as impressive as their speed. The American dwarf mistletoe’s action, for instance, is hot. Truly hot.

This parasitic plant grows in bulbous sprigs from the branches of pine trees along the West Coast. When it’s time for this parasite to move on, the mistletoe shoots out seeds at speeds of about 20 meters (65 feet) per second. The mystery was how it managed this feat.

Then, in 2015, researchers showed that this seed dispersal was triggered by self-generated heat. The biologists had been studying the mistletoe with thermal imaging (which displays temperature differences). This imaging could display tiny changes in temperature across areas smaller than a millimeter (a few hundredths of an inch). About one minute before the mistletoe is due to release its seeds, the plant will warm up by roughly 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit).

Mitochondria are structures in cells that can generate heat. And they were responsible for the intentional fever in these plants. Like a lit fuse, the cell heating triggered a gooey gel in the plant to expand. And that physical expansion propelled the seeds explosively.

One of the smallest and strangest sources of plant motion was reported in the February issue of the journal AoB Plants. With cameras able to snap pictures at a rate of 1,000 frames per second, researchers recorded tiny movements in the moss Brachythecium populeum (Brak-ee-THEE-see-um Pop-yu-LAY-um). One might liken this plant to a soccer star. It can kick with its “teeth,” bendy tissue surrounding its spores. When their microscopic teeth absorb water, they bend and warp. As they dry, the teeth suddenly flick outward, lofting the spores to where they can get spread by the winds.

One month after this report, researchers described a new plant move that resembles the way a lacrosse stick flings a ball. The move showed up in the hairyflower wild petunia (Ruellia ciliatiflora). The flower (which isn’t a real petunia) has elongated seedpods. Each pod holds about 20 disk-shaped seeds. Hooks hold each seed in place.

As it grows, a seedpod begins to strain at its seams (which can weaken if they get wet). When the pod finally splits open, those inner hooks will fling out the seeds, imparting a dizzying spin on each. The seeds can undergo nearly 100,000 revolutions per minute — the fastest spin witnessed in any plant or animal. Interestingly, the researchers report, it’s this spin that keeps the flight of these seeds stable.

Physicist Eric Cooper and his colleagues at Pomona College described their findings in the March 2018 Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Story continues below video.

Plant hustle

Storing and releasing energy through mechanical instabilities offers one way for plants to master speed. It helps some of them quickly capture insects, a good source of nutrients that plants might not be able quickly mine from the soil. It helps other plants disperse their offspring great distances. This may confer an advantage over plants that don’t.

But understanding how botanical speed demons evolved remains largely a mystery. One recent clue might shed some light on the bladderworts’ path to speed. Anna Westermeier works at the University of Freiburg in Germany. She turned up one species that had developed a trap-like structure. But this “trap” couldn’t catch anything. Why? It didn’t open or close, she reported last year in Scientific Reports.

The structure appears to be a primitive form of the plant. Here, the trap is not fully functional, she notes. Identifying relatives that have evolved parts of what they would need for speed could help reveal how rapid motions emerged.

Whitaker hopes to find similar early stages of structures that would go on to produce speed in other plants — ones that now disperse their seeds explosively.

Karl Niklas is a plant expert at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. He has studied plant evolution for more than 40 years. Finding plants that can move quickly is “not surprising at all,” he says. In fact, he thinks it naïve to view plants as largely slow, boring and passive. They’re actually adaptable. And those are among the reasons why he suspects “plants will be around a lot longer than we will.”