To limit pollution, new recipe makes plastic a treat for microbes

The microbes can break the plant- and algae-based material down within a few months

Microplastic bits can show up anywhere in the environment, including soil (as here). A new plastic can break down when exposed to certain bacteria. That should limit the ability of those plastic bits to stick around long enough to harm ecosystems — and people.

Svetlozar Hristov/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Skyler Ware

Plastic pollution is hurting the planet. Even when plastics break down, tiny bits of them still end up polluting the air, the oceans, our food — and even our blood. But a new material might help limit that.

“We’re basically running a giant experiment right now, in terms of what microplastics and nanoplastics are doing to us,” says Michael Burkart. He’s a chemical biologist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). He’s also a founder of Algenesis Materials. It’s a company developing a new plastic.

Most plastics have been made from crude oil, a fossil fuel. Four years ago, Burkart’s team at UCSD developed a new type. They made it from building blocks that can be produced by algae. Now, they’ve shown that this plastic breaks down quickly when a particular species of bacteria dine on it.

The researchers described the finding March 12 in Scientific Reports.

In the environment, larger plastic pieces tend to break down into tinier and tinier bits. If the starting plastic is made from fossil fuels, those bits can take centuries to break down completely. In contrast, Burkart’s team reports the new plastic shouldn’t stick around long enough to harm wildlife (or us).

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Microplastic-munching microbes

The new plastic is a type of polyurethane. Such plastics are used to make foams, paints and adhesives, among other things. The new, biodegradable type contains many chemical building blocks. Small chemical groups known as esters link all those building blocks into a long chain. Bacteria can break apart those esters, releasing the building blocks.

Those building blocks are made from ingredients produced by plants and algae. Many types of microbes break down plants and algae and eat those building blocks. The researchers suspected those microbes might do the same thing to the building blocks of the new plastic.

To test that, Burkart’s team broke their new plastic into tiny particles. They did the same with a different type of plastic made from fossil fuels. It’s known as ethyl vinyl acetate, or EVA. Then researchers mixed these microplastics with fresh compost — a moist mix of decomposed plants, food waste and microbes. After 90 days, 68 percent of the new plastic had broken down. That number climbed to 97 percent after about seven months. In contrast, the researchers saw no EVA breakdown throughout that time.

Compost has everything the plastic needs to degrade: microbes to break it down plus water. The material also can break down in wet soil or the ocean.

But the new plastic won’t break down while you’re using it, says Stephen Mayfield. He’s a molecular geneticist at UCSD. He’s also the chief executive officer of Algenesis Materials. To break down the microplastics, “you need them to be wet 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” he says. “If you break that cycle, even for a short period of time, you kill the microorganisms.”

The plastic breakdown was efficient

When microbes break down plant materials, such as cellulose, they release carbon dioxide (CO2), a greenhouse gas. The researchers decided to compare the CO2 output of microbes dining on the new microplastic to when they ate cellulose.

The new plastic’s breakdown released just as much CO2 as when the microbes ate the same amount of cellulose. This suggests the microbes were breaking down the plastic about as well as they do plants. The scientists even found one bacterium that can survive just by munching bits of the new plastic.

Finally, the UCSD team made a cell phone case from a similar polyurethane that microbes can break down. They left it in moist compost for a year. Afterwards, the case was brittle and discolored. Those changes indicate that microbes living naturally in the compost were breaking it down.

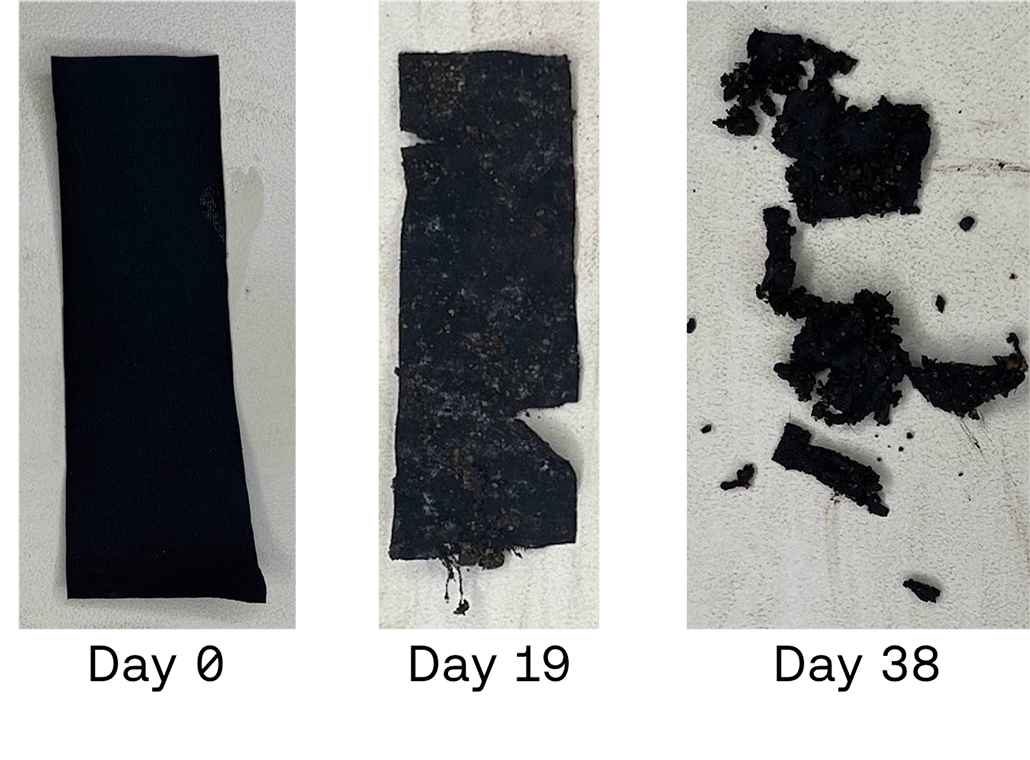

The scientists also coated a piece of fabric in the new plastic. After being mixed with the compost for two weeks, that fabric easily broke apart. Another piece of the coated fabric was not composted. It was still intact after two weeks.

“I’m so excited for this in the textiles space,” says Lisa Erdle. She’s an ecotoxicologist at 5 Gyres. It’s a nonprofit institute in Santa Monica, Calif. Erdle did not take part in the new work, but she does study how microplastics affect the environment.

Polyurethane is sometimes used to coat natural fibers, like wool and cotton, for clothing, Erdle says. Over time, that plastic coating flakes off, “fragmenting into smaller and smaller pieces and never going away.” Having something that can readily be broken down by bacteria, she says, is better than “having persistent plastic in the environment.”

Moving forward, Algenesis Materials hopes to start making biodegradable, single-use plastics, says Mayfield. These might, for example, replace materials currently used in food packaging, he says. And then “you just chuck that thing in a compost pile and it becomes mulch in about 90 days.”

“What I want is for people to have hope that there are solutions” to the microplastics problem, says Burkart. “We actually don’t have to accept the status quo.”