Pluto, plutoid: What’s in a name?

Former planet gets new label

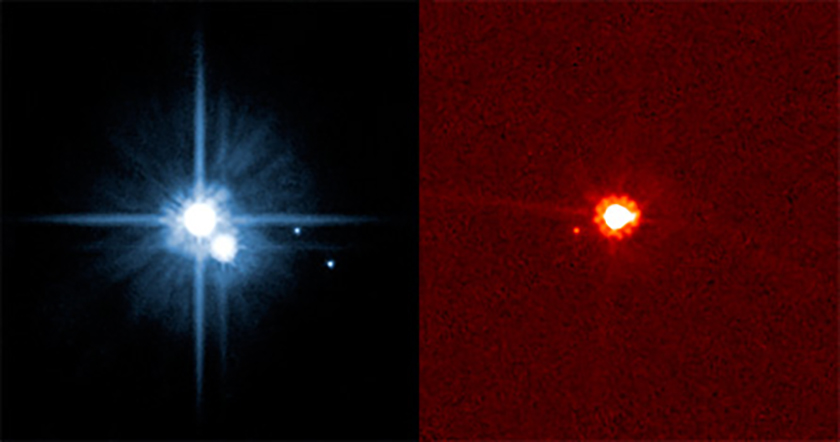

These images show the first plutoids. The blue blob is Pluto. The red one is Eris. Both objects lie far from Earth, beyond Neptune, and are large enough that gravity pulls them into spherical forms.

NASA

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, wrote William Shakespeare. But what would astronomers say about a planet by any other name?

It’s a question astronomers have been talking about since 2006. That’s when an international organization changed the classification of Pluto from planet to “dwarf planet.” That same organization has now come up with yet another term. It describes them as a new class of Pluto-like objects.

Objects in this new category would be called “plutoids.” According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), plutoids are dwarf planets that orbit the sun beyond the orbit of Neptune.

This sets these plutoids apart from another solar system dwarf planet called Ceres, It resides in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It’s an important distinction, says Brian G. Marsden. He’s an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. Ceres is a rocky dwarf planet,. Pluto is icy. Because the two have different physical traits, they should not be grouped into the same category.

|

|

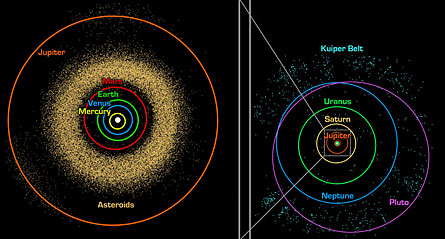

This graphic shows the Asteroid Belt and the Kuiper Belt. The Asteroid Belt, the fuzzy ring of dots on the left, is where the dwarf planet Ceres is located. The belt lies between the orbit of Mars and Jupiter, at the edge of what’s called the inner solar system. The image on the right shows the Kuiper Belt, at the outer edge of the solar system. This belt is home to Pluto, Eris and probably other plutoids.

|

| NASA |

The new category and name reflect a growing body of evidence showing that Pluto shares its neighborhood with numerous other objects in the outer solar system that all orbit the sun. Planets, on the other hand, travel alone in their orbits with no nearby neighbors except their moons. The observation suggests that Pluto isn’t big enough and heavy enough to have the gravity to “clear its orbit,” removing nearby objects by either slinging them farther out into space or pulling them toward its surface.

The ability to clear the orbit was one of the main criteria the IAU used in 2006 to justify changing Pluto’s status from planet to dwarf planet. A planet should be large enough that its gravity dominates everything else near its orbit, IAU said. It’s an idea based on astronomers’ theories about how the solar system originally formed.

Billions of years ago, they say, the solar system was made up of many small objects spread in a disk around the sun. Some of those objects grew by pulling other objects into them, much the way a snowball grows when you add more snow to it. As these objects grew larger, their gravity attracted more pieces of material to them. Eventually, they swept clean the entire zone in a wide path around them. In other words, they “cleared their orbit” of other material. Because numerous other objects orbit the sun near Pluto, some astronomers say it doesn’t have the size to clear its own orbit.

Pluto is still large enough for its own gravity to crush its mass into a spherical shape. And that sets it apart from other, smaller solar system objects like asteroids. So classifying it as a dwarf planet explains how it interacts (or, really, how it doesn’t interact) with other objects in the solar system. The additional classification as a plutoid makes clear where in the solar system Pluto and other objects like it reside.

|

|

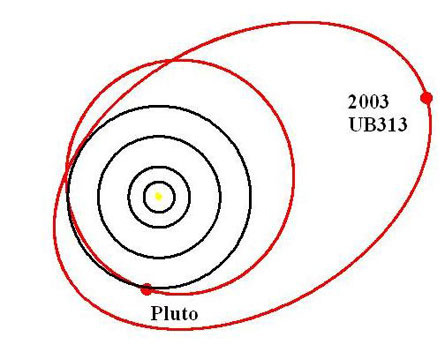

This image shows the sun and the orbits of the outer planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. The picture shows that the orbits of the two, new plutoids — Pluto and Eris (originally called 2003 UB313, as marked here) — in red. By definition, the plutoids’ orbits lie past Neptune’s orbit.

|

| Caltech |

So far, astronomers have named one other plutoid — the dwarf planet Eris, whose discovery in 2003 sparked the controversy over whether it was correct to continue calling Pluto a planet. Since then, astronomers have found other plutoids, Marsden says.

“Now that we’ve gotten the go-ahead from the IAU, the third plutoid will be named soon,” he says.

Regardless of the terminology scientists use, Pluto and other objects like it will continue to teach us more about the structure of the solar system. Losing its classification as a planet doesn’t make Pluto any less deserving of study, says Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

“Pluto is still Pluto,” he says. “And I am quite sure it does not concern itself with what we choose to call it. And whatever we call it, it’s no less interesting a cosmic object than it was before all this began.”