The power of ‘like’

A single 'like' can make a social-media post more popular and even affect how teens behave

People who post on social media want their offerings to garner legions of likes. Most readers also tend to share those posts that have gotten a large quantify of “likes.” So very popular posts go on to become even more popular. This can greatly affect what goes viral.

nadia_bormotova/iStockphoto

This is the second of a two-part series

Like it or love it, social media is a major part of life. Teens spend more than half of their waking hours online. You use some of that time to post pictures and to create profiles on social media accounts. But most of what you do is read and respond to posts by friends and family.

Clicking on a thumbs-up or a heart icon is an easy way to stay in touch. But those “likes” can have power that goes beyond a simple connection. Some social media sites use those likes to determine how many people eventually see a post. One with many likes is more likely to be seen — and to get even more likes.

What’s more, viewing posts with a lot of likes activates the reward system in our brain. It also can lower a viewer’s self-control. And posts related to alcohol may encourage teens to drink. That means that what you like online has the power to influence not just what others like, but even what they do.

Popularity on the brain

It’s no surprise that feedback from peers affects how we behave. And not always in a good way.

For example, in one 2011 study, teens doing a driving task in a lab took more risks when their friends were around. Researchers also looked at the teens’ brains during this task. They saw activity in a part of the brain that’s involved in rewards. This area is known as the nucleus accumbens. That suggests these teens were changing their behavior to try to get social approval, explains Lauren Sherman. She’s a cognitive neuroscientist at Temple University in Philadelphia, Penn. Cognitive neuroscientists are researchers who study the brain.

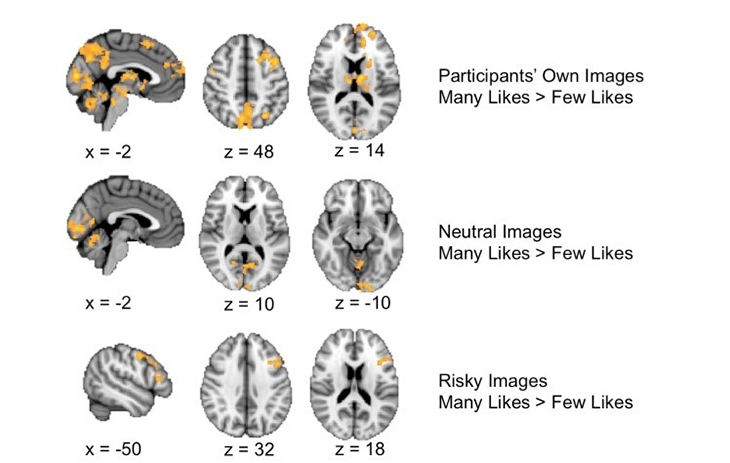

Sherman wanted to know whether teens make similar changes to their behavior when they use social media. To find out, she and her team recruited 32 teens for a study, last year. All submitted photos from their personal Instagram accounts.

The researchers mixed the teens’ photos with other pictures from public Instagram accounts. Then they randomly gave half of the images many likes (between 23 and 45; most had more than 30). They gave the other half no more than 22 likes (most had fewer than 15). The participant’s own pictures were evenly divided between getting many or few likes.

The researchers told the participants that about 50 other teens had already viewed and rated the photos. That let the teens know how big the audience was. It also gave them a feel for how popular the pictures were.

The researchers wanted to see how the participants’ brains were responding to the different images. To find out, they had the volunteers view the photos while they were inside a magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, machine. It uses a strong magnet to record blood flow in the brain. When brain cells are active, they use up oxygen and nutrients. MRI scans show where blood flow has increased because of this activity. When people perform some task while in the MRI machine, this test is now known as functional MRI, or fMRI.

While the teens were in the machine, researchers asked them to either like an image or skip to the next one. Teens were much more likely to like images that seemed popular — those that had more than 23 likes, Sherman’s team found. The kids tended to skip pictures with few likes. And the brain’s reward pathways became especially active when the teens viewed their own photos with many likes.

Story continues below image.

Likes can have a subtle but significant effect on how teens interact with friends online, these data suggest. “The little number appearing below a picture affects the way [people] perceive that picture,” Sherman reports. “It can even affect their tendency to click ‘like’ themselves.”

A like is a social cue, Sherman explains. Teens “use this cue to learn how to navigate their social world.” Positive responses to their own photos (in the form of many likes) tell teens that their friends appreciate what they’re posting. A brain responds by turning on its reward center.

But seeing someone else’s popular photo didn’t necessarily turn on that reward center. Sometimes looking at the picture instead affected behavioral attitudes. For instance, cognitive control helps people maintain self-control. It also helps them think about plans and goals. The brain region linked to cognitive control tended to become less active when looking at some photos — no matter how many likes they might have. What kinds of pictures turned off this brain control region? They were photos showing risky behaviors, such as smoking or drinking.

Viewing pictures like these could make teens let down their guard when it comes to experimenting with drugs and alcohol, Sherman worries. “Repeated exposure to risky pictures posted by peers could make teens more likely to try those behaviors.”

Small act, big impact

Clicking “like” is a simple act that can have complex results. In fact, a single like can have a big impact on a post’s popularity and reach, say Maria Glenski and Tim Weninger. These computer scientists work at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Glenski and Weninger studied the social news site Reddit. Its users can respond to headlines by clicking an arrow that points up or down. An up arrow, or “upvote,” is similar to a like. The researchers created a computer program that scanned Reddit every two minutes for six months. During each scan, the program recorded the most recent post on the site. Then it randomly upvoted the post, downvoted it or did nothing. By the end of the study, the program had upvoted 30,998 posts and downvoted 30,796. It left alone another 31,225 posts.

Glenski and Weninger watched to see how popular each post was four days after their program had interacted with it. The final score they used was the number of upvotes minus the downvotes. The researchers considered posts with a score of more than 500 to be very popular.

Posts that their program had upvoted did better. These posts were eight percent more likely to have a final score of at least 1,000, compared to posts the program had ignored. And upvoted posts were almost 25 percent more likely to reach a final score of 2,000 — making them extremely popular. In contrast, posts that the program downvoted ended up with scores five percent lower, on average, than were posts that the program had ignored.

“Early up-ratings or likes can have a large impact on the ultimate popularity of a post,” Glenski concludes. “People tend to follow the behavior of the group.” If other people have liked a post, new viewers will be more likely to like it too. And that popularity can feed on itself.

Many social media sites share more of the higher-ranked — or more popular — posts. As a result, “people are more likely to see what others have positively rated,” Glenski says. So the posts that get the most likes tend to spread even more widely.

Teens should keep in mind, Glenski cautions, that just because a post is popular doesn’t mean it is a quality post. Similarly, she adds, people should pay careful attention to what they like, share or comment on. “Your actions influence what other people see and hear in the media.”

Risky business

Popular photos might signal to teens that what’s in those photos is socially acceptable. If those images show alcohol use or other risky behaviors, this could lead teens to make bad choices. That’s what Sarah Boyle concluded from a study she ran last year.

Boyle is a psychologist at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, Calif. Her team recruited first-year college students to see if — and how — social media posts might affect underage drinking. Their participants included 412 incoming students. All were under 21 (the legal drinking age).

Students completed two surveys. They took the first between September and October. This was 25 to 50 days into the first half of the school year. They filled out a survey again between February and March, well into the second half of the school year. Each survey asked how much alcohol someone drank, and how often. It also asked why that person drank and what role they felt drinking plays in the college experience.

Each survey also asked students how frequently they checked Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat. And when they did go on social media, had they seen alcohol-related posts? The researchers then compared responses from the first and second surveys.

Students who saw alcohol-related posts during the first six weeks of school were more likely to drink alcohol by the second survey, the data show. Men increased their drinking more than women did. Seeing alcohol-related posts on social media increased how much they thought other male students were drinking, Boyle says. Those posts made the young men see drinking as an important part of their college experience. “These things, in turn, led them to drink more themselves,” Boyle says.

Women saw alcohol-related posts also began to view drinking as part of the college experience. They, too, increased their drinking, just not as much as the men did. However, the posts didn’t change their idea of how often other women drank. That’s probably because male students made the most alcohol-related posts, Boyle observes.

A difference also emerged between social media sites. More posts about alcohol appeared on Instagram and Snapchat than on Facebook. Boyle suspects this is because fewer parents, professors and other older adults use Instagram and Snapchat. Instagram’s filters also may allow people to glamorize photos, making alcohol more attractive, she adds. Similarly, people may post photos of alcohol to Snapchat because they know their posts will disappear.

The important take-home message here, Boyle says, is that what students see on social media can influence their attitudes about drinking, Boyle says. “The problem with social media is that posts can distort reality.” Social media users see only highlights from the party. These are the posts that others like. People rarely, however, post pictures of their hangovers, poor grades or drinking-related injuries and accidents, she notes.

Neuroscientist Sherman hopes that all tech users will become thoughtful about their use of social media. Our online experiences are shaped by others’ opinions. Going along with the crowd isn’t necessarily bad, she says. But teens need “to be aware that peer influence is a constant factor whenever they use social media.”

Glenski, the computer scientist, agrees. Social media “shapes how we perceive the world around us,” she says. Your online ratings have a big influence on what others see and hear. So it’s important that you read carefully. Think about what you like and upvote, she says. And keep in mind that “Your digital votes matter.”

Check out part 1: Social media: What’s not to like?