Microscopic black holes may be flying through our solar system

Massive but atom-sized, these flybys could jostle the orbits of planets and satellites

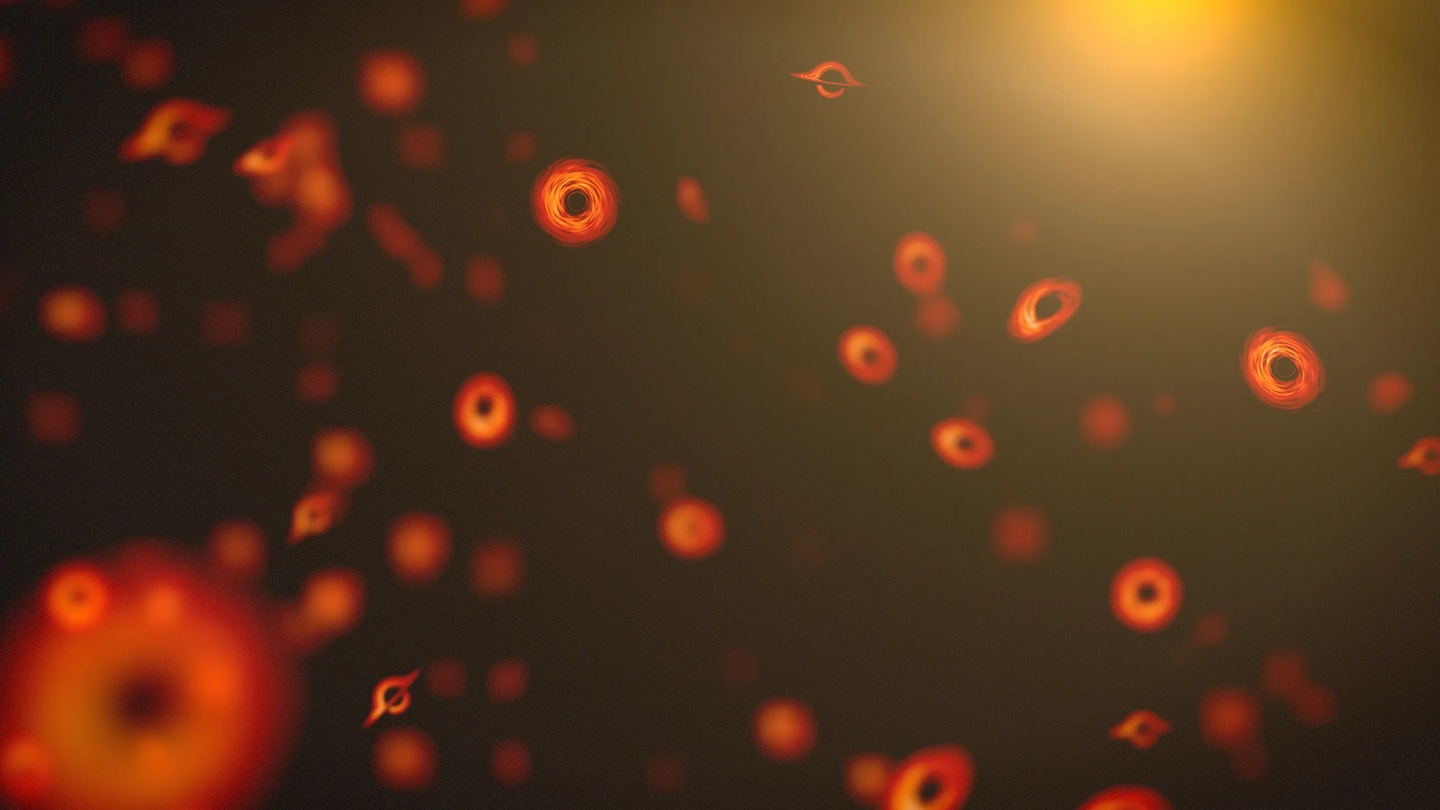

A teeny tiny black hole in the solar system (illustrated) could mess with planets' orbits as they move around the sun.

Benjamin V. Lehmann, with use of SpaceEngine@Cosmographic Software LLC

Microscopic black holes could be careening through our solar system unnoticed. But their days of stealth may be numbered. Two research teams have just proposed ways to spot such baby black holes — if they truly exist.

These black holes would pack the mass of an asteroid into a space about the size of a hydrogen atom. Scientists suspect that objects like this could have formed in the very early universe. For that reason, they are known as primordial black holes. (Primordial means “existing from the beginning.”)

One way to find primordial black holes is to look for the effects of their gravity on planets. Another way is to look for their gravitational pull on satellites. Researchers shared these ideas on September 16 and 17 in Physical Review D.

Finding primordial black holes could help solve a big mystery about the universe. Namely: What is dark matter?

That invisible stuff makes up 85 percent of the matter in our universe. Scientists know it exists because its gravity pulls on things we can see. Stars within galaxies, for instance. But no one knows what dark matter is made of.

Researchers have searched high and low for particles that could explain dark matter. But those searches have all come up empty. If tiny black holes are caught wandering the cosmos, that could explain what makes up some or all dark matter.

Small objects, big gravity

Black holes typically form when a dying star collapses. This creates a black hole with at least several times the mass of the sun. Some scientists think smaller black holes might have formed in the early universe. Back then, bits of space might have collapsed on their own. That would have pinched off fairly small bits of matter into teeny tiny black holes.

Some of those primordial black holes may have asteroid-size masses. If so, they might whiz through the inner solar system about once a decade, researchers estimate. That means there’s no need to worry about a tiny black hole crashing into you. That’s less likely than a peanut thrown at random hitting a specific blade of grass in a lawn the size of a trillion football fields!

When a tiny black hole passes near a planet, though, it could have noticeable effects.

“The incredibly strong [gravity] of this primordial black hole will [make] Mars wobble in its orbit around the sun,” explains Sarah Geller. This cosmologist is based at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She worked on the planetary wobble study. In the future, Geller and her colleagues plan to test this idea using detailed models of the solar system.

A primordial black hole could also jostle satellites. Imagine a black hole with the mass of an asteroid coming within the moon’s distance from Earth. It could change the altitudes of satellites a small but detectable amount.

“That’s very exciting to know,” says Sébastien Clesse. “We have some probes that could be used to really detect baby black holes in the solar system.” Clesse is a cosmologist at Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium. He worked on a satellite-based detection method.

A satellite search would be useful for finding black holes of smaller masses than the planetary-wobble technique. “It is very complementary,” says Bruno Bertrand. An astrophysicist, he’s based at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Uccle. He worked on the satellite research with Clesse.

When to blame black holes

Plain old asteroids could mimic the gravitational effects of the tiny black holes. But the black holes would have speeds of roughly 200 kilometers (about 100 miles) per second. And they would come soaring in from outside the solar system. That’s rare for space rocks.

“We have never seen an object pass through the solar system that would have the characteristics [of] a black hole,” says Ben Lehmann. But if scientists do spot a planet wobbling in its orbit, they would still want to check for any space rocks that might explain it, he says. To do that, they’d need to detect a planet’s wobble in real time. Lehmann is a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. He helped devise the planetary-wobble method.

Other celestial effects could also tweak planetary orbits. Those would need to be ruled out before blaming a tiny black hole, says Andreas Burkert. He’s an astrophysicist who did not take part in either study. He works at Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich in Germany.

The solar wind of charged particles streaming out from the sun can affect the orbits of planets, Burkert notes. And confirming that changes to satellite motions are due to black holes could be quite challenging. A tiny black hole passing close enough to Earth to be detected this way could be extremely rare, he says. Right now, he adds, “I don’t think it’s realistic.” But he remains “optimistic that it might be possible at some point.”