This printer makes ‘visual’ aids for people with sight problems

A physicist’s blindness inspired touchable and talking graphs, charts and maps

A computer can read aloud as someone touches different parts of a raised-dot diagram. The text can be read in braille, too.

ViewPlus Technologies, Inc

Maybe you’ve heard the saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” It means that some information is best conveyed visually. And that’s especially true in many research fields, says electrical engineer Dan Gardner.

But what if you can’t see?

Dan’s dad learned firsthand just how hard some science work can be when he could no longer see pictures, graphs or other visual displays of his data.

John Gardner was a solid-state physicist at Oregon State University (OSU) in Corvallis. His job involved using “the properties of the nucleus [of an atom] to learn something about the solid [state]” of materials, he explains. For many projects, he and his team added tiny bits of radioactive impurities — think of them as tags — to different solids and liquids. Then they applied a strong magnetic field to each material.

Energy from the “tags” would be released in the form of gamma rays — a type of radiation. The rays would be at right angles to each other. But there was also some wiggle, some variation in the angle of an emerging beam of energy. The wiggles came from other atoms in the material, which were all moving around.

“What we did,” John explains, “was to evaluate the wiggles.” That gave his team useful information about the materials they studied. Yet to do that took a lot of complex math. And it involved studying a lot of graphs.

Although blind in one eye, John could see with the other. Or he could until too much pressure built up from fluid in the good eye. He needed surgery. Unfortunately, his eye reacted badly. This left the scientist completely blind.

John still wanted to do physics. But to do that, he had to interpret each graph precisely. “Getting it exactly right all the time was incredibly important,” he explains. And that, he notes, “was not easy to do when I couldn’t see [those graphs].” Once he became blind, he had to approach things differently.

For a while, he still supervised graduate students. They would tell him what a graph showed. That helped somewhat. But he wasn’t satisfied. He wanted to more directly “see” those graphs and data that underpinned his work.

His solution: Design a system to make touchable data graphs and other “visual” aids for himself and others who couldn’t see well, or at all.

John got a team together at OSU. With financial help from the National Science Foundation (NSF), they invented a new type of printer for these data and graphs.

Braille is a form of printing for the blind. Raised dots take the place of printed letters. But regular braille couldn’t handle a lot of advanced math. It didn’t work well for scientific graphs and charts, either, John explains. People at NSF asked John if his team could invent a better way. He told them he thought so. Afterward, NSF gave his group funding to give it a try.

Together, John’s team worked to apply the concept of braille to math and visual data.

Their novel printer squeezes paper between pointy tools called punches and little cups, called dies. When the punches press into the dies, they make raised dots on the paper between them. This type of printing with raised dots is called embossing.

The team showed NSF how the concept worked. “They were absolutely blown away,” John recalls. NSF gave his group another grant for more work. And John moved from working on physics to working full-time on developing this technology. His new job: creating new tools for scientists with vision problems.

How to make data ‘show and tell’

John Gardner set up ViewPlus Technologies to make the new printers — and make them better.

For instance, the printers had to work with common software programs such as Word and Excel. They also needed to increase how many dots per inch, or DPI, the machine could emboss. The more dots per inch, the sharper and more detailed a graph or chart could be.

Users would also need to be able to tell different parts of a map or chart from each other. One bar chart might compare several groups in a study, for example. Someone might display this on a regular chart using different colors, shading or other visual patterns. John’s team had to figure out ways to display such contrasts. They decided on “shading” such regions using dots with different heights.

The team also has developed interactive “talking” pictures. This system combines a tactile (TAK-tyle), or touchable, printout with a computer to make interactive graphs and charts. One printer step embosses braille and graphics. Another adds visible ink. Meanwhile, a computer file for the graph has sound information coded for different parts of the image.

Now a sighted teacher or low-vision user can work with the same document. A person puts the tactile printout over a touchscreen. That touchscreen is hooked up to a computer, and the corresponding computer file is open. As someone touches different parts of the printout, this activates the touchscreen below. And that triggers the computer to read aloud the matching audio information for the touched spot. Someone doesn’t even need to know how to read braille to use this system.

One size doesn’t fit all

Imke Durre has one of the earliest versions of the Gardners’ embosser. She is a climate scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration office in Asheville, N.C. Like John Gardner, she is blind.

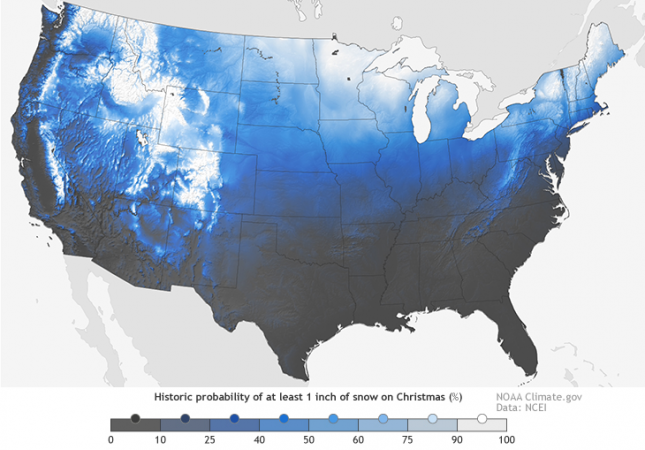

Durre’s group collects and studies weather and climate data. Among other things, these data help her team figure out what’s normal for different locations. The group uses a lot of maps and charts in its work. Three years ago, Durre and a colleague described how likely it is for parts of the United States to have a white, or snowy, Christmas. A map displayed their results.

Durre uses her embosser to print braille. But she’s found that it isn’t always convenient to use for graphics.

Sometimes, for example, a sighted person had to help her make a graph bigger or pull it out from some larger document. Those extra steps take time and effort. Often, “it’s more efficient to have a sighted person just describe to me what the graph looks like,” Durre points out.

But tech for people with disabilities doesn’t help all people equally. It isn’t one-size-fits-all.

Durre can see “a lot of value” for the embosser and touchscreen products in schools. Students need to learn how to read and make graphs. And teachers and aides can help them use these new products.

Early versions of the embosser did need a sighted person to prep the text that goes along with a graph, John Gardner says. The latest printers let blind people tinker with text. They also can resize images and change how a graph’s shaded areas are filled in with dots. They even can print braille and audio-touch graphics by themselves.

John Gardner often talks at conferences about the tools his group has been developing. Assistive technology deals with tools that make life easier for people with disabilities. This past spring, John described the new audio-touch combo at the CSUN Assistive Technology Conference in San Diego, Calif.

For John, such products have made a huge difference. “My biggest joy [comes from] the great maps I can read,” says John Gardner. “I enjoy reading historical novels, traveling and other activities that involve maps. Now I can have maps again.”

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.