Profile: Looking for life beyond the solar system

Exoplanet pioneer Sara Seager explores the atmosphere of alien worlds

An examination of Earth’s atmosphere would turn up oxygen, methane and other telltale signs of life. Sara Seager is looking for similar signs on exoplanets — planets beyond our own solar system.

MIT/Patrick Gillooly

By Ron Cowen

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — The summer before astronomer Sara Seager entered graduate school, she spent two months canoeing the wilderness of Canada’s Nunavut Territory. Her heavy load of gear included a physics book. Mike Wevrick, her future husband, journeyed with her. Together, they paddled rapids and crossed lake after lake. In between, they hauled their canoe through forests.

One morning, Seager spotted a fire in the distance. She wasn’t worried. Her only thought was that forest fires appeared to be common here. But that evening, a massive headwind whipped up. It turned the calm lake they had been paddling into a cauldron of whitecaps and swells. Powered by the wind, the fire shifted. It now burned right in their path. Waiting for the winds and fire to die down, the couple set up camp for the night.

The next day, thinking the worst was over, they paddled up a narrow river. Suddenly, smoke darkened the afternoon sky. Orange flames raced toward the right side of the river. Panicked, the two paddled hard to the other side. Climbing high above the river, they made a campsite in an open spruce forest.

By morning, the fire had passed and they were safe. But Seager never forgot the experience.

Nor would it be the last time the sky in a faraway place would leave a lasting impression on her.

Seager soon would find herself studying the atmospheres of places even more remote than the Nunavut Territory. She had just won admission to Harvard University’s doctoral program in astrophysics. There, she would be among the first to investigate the skies of other worlds — thousands of planets that have been turning up well beyond our solar system.

Today, 21 years later, Seager is attempting to probe what makes up the atmospheres surrounding those distant worlds. That gas can reveal a lot about a planet, including whether it’s home to life. For example, the oxygen and methane in Earth’s atmosphere are both signs of possible life. Life generates other gases too. Finding them above a distant planet could lead to the discovery of Earth’s twin — another relatively small chunk of rock that also supports life. That life could be as simple as bacteria. Or it could include a civilization more advanced than our own.

When Seager turned 40 in 2011, instead of hosting a big party, she threw a conference. She invited friends and colleagues to come together and brainstorm how best to find Earth’s twin. Pacing the stage and speaking in her rapid-fire style, she told the audience that finding Earth 2.0 was not the certainty she had once assumed. But together, with hard work and imagination, she thought they could do it.

Discovering a second Earth, she says “is the start of an incredible, centuries-long phase of exploration.” She envisions that “hundreds or a thousand years from now people will be traveling to the other worlds.” And they’ll look back upon us “as the generation that first found the Earth-like worlds,” she suspects.

But when Seager started her career, she didn’t focus so much on the future. In fact, her very first studies led her back in time, to the dawn of the universe.

Starting with the Big Bang

Seager’s first work at Harvard explored a time before there were any planets, much less stars. This was a few hundreds of thousands of years following the Big Bang — the origin of our universe. Astronomers wanted to know how the oldest light in the universe, from nearly 14 billion years ago, interacted with hot gases.

Telescopes today can gather some of that ancient light. And like all light, it tells a story.

Take the white light we see glowing from a light bulb. That light is actually composed of many colors, or wavelengths. When light passes through gas or dust, the atoms and molecules in that material absorb specific wavelengths. An instrument called a spectrograph can reveal which wavelengths have been absorbed. They show up as dark gaps when white light is broken into its component colors. Those gaps are like fingerprints. They reveal the identity of the atoms and molecules in the absorbing material.

Seager used the ancient light to decode what happened in the early universe.

Meanwhile, other researchers were uncovering surprises about our galaxy today.

In 1995, for instance, astronomers discovered the first planet orbiting a star similar to the sun. Within four years, researchers discovered seven more such worlds, or exoplanets. These discoveries caused a sensation. They suggested that planets might be common throughout our galaxy. Immediately, people wondered if some might host life.

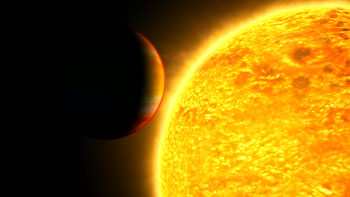

The first planets were downright weird. Most were giant balls of gas, like Jupiter. But unlike Jupiter, they orbited much, much closer to their parent stars than Mercury (our solar system’s innermost planet) circles the sun. Astronomers nicknamed these roasting planets “hot Jupiters.”

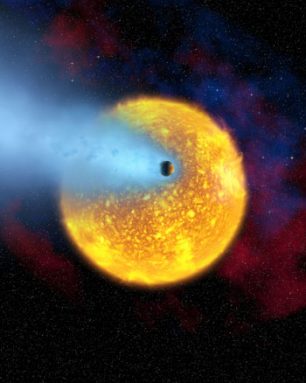

ALIEN ATMOSPHERES This illustration shows how a star’s light illuminates the atmosphere of an exoplanet. That light can reveal important information about the atmosphere’s makeup — including hints of any life that might call the alien planet home. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center |

At first, it seemed just about impossible to learn anything about these planets other than their mass and distance from their parent stars. Then Seager’s career took an unexpected turn.

At Harvard, Dimitar Sasselov was Seager’s advisor. And he realized that the techniques Seager was using to explore the early universe could work with the hot Jupiters too. She would use a spectrograph to look at starlight, but only starlight that first had passed through the atmospheres of these exoplanets. That spectrograph can reveal wavelengths that have been absorbed by a gas. They show up as dark gaps when white light is broken into its component colors.

Later, Seager began to address an age-old question: Are we alone in the universe?

As astronomers find more and more exoplanets, there is no way — yet — to travel to these worlds to find out. But Seager had found a way to answer this question, nevertheless.

The leap to alien worlds

First, consider Earth. Nitrogen, oxygen and a host of other gases make up the air we breathe. Those gases absorb sunlight. Astronomers have used spectrographs to show this. When they break up sunlight that has passed through the atmosphere into its component colors, gaps between the colors emerge. And each particular gap points to which gas molecules absorbed some of the light.

If Seager had had a spectrograph with her in northern Canada when the fire neared her, she could have turned the device toward the sun. Its measurements would have let her identify what gases had been streaming off of the flames.

Now consider what astronomers might learn if they could observe light from a star shining through the atmosphere of a distant exoplanet. Just as on Earth, scientists could in theory determine the recipe of the gases in its atmosphere. This was the idea that Seager pursued.

Back in the late 1990s, some scientists thought it pointless to even wonder what the atmospheres surrounding these planets might look like. To start, those planets were too faint to be seen. Astronomers had detected them only indirectly, by the tug they exerted on their parent stars. Any direct observation might be decades away. Until then, it didn’t seem there was much sense in trying to predict the composition of these oddball worlds.

But Seager wasn’t discouraged. Even so, some Harvard scientists worried Seager might be wasting her time.

She would prove them wrong.

Seager showed that the atmosphere of an exoplanet could be detected. The opportunity came each time an orbiting planet passed between its parent star and a telescope orbiting above Earth. That passage of a distant planet in front of its star is known as a transit.

Even as Seager worked, she set aside a month each summer to go paddling or camping. In 1999, she received her doctoral degree. It was the first time any student in the United States had earned a PhD studying exoplanets. She presented her research to a packed audience at Harvard.

Shortly after graduation, Seager calculated that it should be relatively easy to detect even a small concentration of sodium in the atmosphere of an exoplanet. That element would produce a detectable gap in the starlight.

In 2001, just two years later, astronomers confirmed Seager’s prediction. The researchers used the Hubble Space Telescope to detect sodium in the outer atmosphere of a hot Jupiter. It was the first time that the atmosphere of a planet outside our solar system had been detected. The planet orbits a sunlike star known as HD 209458.

Seager marveled at how quickly and smoothly observations were confirming her predictions.

Choosing a career

Seager’s childhood in Toronto, Canada, had not been as smooth. Her parents divorced while she was in primary school. Seager remained much closer to her father, a physician. David Seager had two goals for his daughter. The first was that whatever Sara did, she should always believe she could do better. The second was she should choose a career, such as medicine, that would allow her to support herself. By that second measure, astronomy didn’t seem a great choice.

If David Seager didn’t want his daughter to look skyward for a career, he probably never should have agreed to take the family camping to Bon Echo Provincial Park, in southeastern Ontario. When 10-year-old Sara got out of her tent in the middle of the night and looked up, “I was blown away,” she still remembers. “The sky was so filled with stars that there was very little black space. I just had no idea that all this existed out there,” says Seager. “No one had ever told me about it.”

Although star-struck, it didn’t occur to Seager that she could turn this early interest into her life’s work. That changed at 16. That’s when she learned about astronomy. She had been visiting the University of Toronto. It “was a huge turning point,” she recalls. “I hadn’t known there was such a thing as a career in astronomy.”

By then, Seager was attending the Jarvis Collegiate Institute. This public high school in Toronto offered advanced classes in mathematics. For the first time, Seager began to pay attention in school, especially during math and chemistry classes. “Math is like a puzzle,” she says. “It has this sort of aesthetic level of beauty. But it also has a mechanical function — you start with numbers and you end up with something different.” Chemistry class, by contrast, “opened a fascinating window into how things work at a fundamental level.”

Seager credits one high school teacher with strengthening Sara’s interest in math. She was unusually kind. And when the teen goofed off in her math class, “instead of getting mad and sending me to the principal’s office,” this teacher assigned the girl more challenging problems to work on. And the teen did them.

When Seager entered the University of Toronto in 1990, she decided to study physics — the science for which mathematics provides a backbone. Over time, though, she realized that physics involved too many approximations — short-cuts needed to apply mathematical formulas to real-world problems. Disappointed, the young woman turned to astronomy.

ANOTHER EARTH Here’s Seager describing her work and goals. John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation |

Seager now works at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. Here she is exploring the atmospheres of an astonishing variety of planets. She’s been among the first scientists to analyze the makeup of hot Jupiters and another class of planets dubbed “mini Neptunes.” Those newly discovered planets, which resemble small versions of Neptune, do not exist in our solar system.

Galaxies can hold billions of stars or more. Astronomers already know of nearly 2,000 exoplanets in our galaxy, the Milky Way. Some suspect it may host 100 billion planets.

NASA’s Kepler space telescope discovered many of the known exoplanets. So far, those distant worlds include giants as large as Jupiter and dwarfs the size of Mercury. Tantalizingly, others fall somewhere in between — closer to the size of Earth. Astronomers estimate our galaxy may harbor some 4 billion of these Earth-sized worlds.

Seager isn’t content to find just any Earth-size world. She wants one that would qualify as a true terrestrial twin — a replica of Earth that orbits a sunlike star. Like our own planet, this Earth 2.0 would lie in what astronomers call the “Goldilocks” zone. There, a planet orbits its sun at just the right distance. Temperatures would be just right too — not too hot and not too cold. Water could remain a liquid on its surface. That’s especially important as liquid water is essential for life as we know it.

As part of her hunt, Seager became part of the science team on a NASA mission called the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS for short. This robotic space telescope is set to launch in 2017. It will watch some of the brightest stars in the sky for any temporary but telltale dips in brightness. Those dips could signal a planet transiting its star.

Because Earth-size planets are relatively small, finding them around nearby stars offers the best chance for studying them. Once found, a second and more powerful telescope would then observe the planets in detail. That future mission is called the

. Scheduled to launch in 2018, this telescope could identify chemicals in the atmospheres of the planets that might hint at the presence of any life. Such compounds include methane, carbon dioxide and water vapor. Earth’s atmosphere has them all.

A new type of hunt for alien life

In 2013, Seager won a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award for her contribution to the study of exoplanets. The triumph came on the heels of a terrible loss. Just two years earlier, her husband and outdoor adventure companion, Mike Wevrick, died of cancer. This left Seager alone to support herself and their two young sons.

The collection of canoes and kayaks that Seager had acquired over the years remains untouched in the family garage. Seager often says her husband’s death has only strengthened her commitment to find Earth 2.0.

Talking in her MIT office, high above the Charles River, Seager described some of her latest research. In her rapid, staccato cadence, she talked about expanding her search for signs of life — to exoplanets unlike Earth. Seager is exploring how to spy the chemical signatures in an atmosphere created by forms of life that do things differently than here.

Such alien life might use compounds different from those that are essential to Earthlings. For example, life on another planet might rely on sulfur the same way that all of Earth’s life relies on carbon. If so, Seager wants to know what compounds such life forms would expel into their atmosphere. Eventually, she hopes to look for those gases too.

To get there, Seager has embarked on a new path. She recently led a critical phase of the Starshade project. This proposed space mission would use a giant screen to block the light of bright, nearby stars. With the starlight blocked, Starshade’s telescope could then search for faint planets — even ones as small as Earth — that might orbit those stars.

In another study, Seager has teamed up with a biologist to fully understand which gasses might be produced by life beyond Earth. Along the way, she has learned basic chemistry.

In her personal life, too, Seager, has begun a new chapter. At a weekend astronomy symposium where she was a guest speaker, Seager met amateur astronomer Charles Darrow. Darrow and Seager married in April. Last December, Darrow celebrated Hannukah for the first time, lighting the menorah with Seager and her children.

The candles on the menorah burn for just eight days. But the search for signs of alien life among planets far from our own is a journey likely to occupy Seager for years to come.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

abstract Something that exists as an idea or thought but not concrete or tangible (touchable) in the real world. Beauty, love and memory are abstractions; cars, trees and water are concrete and tangible.

astronomy The area of science that deals with celestial objects, space and the physical universe as a whole. People who work in this field are called astronomers.

astrophysics An area of astronomy that deals with understanding the physical nature of stars and other objects in space. People who work in this field are known as astrophysicists.

atmosphere The envelope of gases surrounding Earth or another planet.

atom The basic unit of a chemical element. Atoms are made up of a dense nucleus that contains positively charged protons and neutrally charged neutrons. The nucleus is orbited by a cloud of negatively charged electrons.

Big Bang The rapid expansion of dense matter that, according to current theory, marked the origin of the universe. It is supported by physics’ current understanding of the composition and structure of the universe.

carbon The chemical element having the atomic number 6. It is the physical basis of all life on Earth. Carbon exists freely as graphite and diamond. It is an important part of coal, limestone and petroleum, and is capable of self-bonding, chemically, to form an enormous number of chemically, biologically and commercially important molecules.

carbon dioxide A colorless, odorless gas produced by all animals when the oxygen they inhale reacts with the carbon-rich foods that they’ve eaten. Carbon dioxide also is released when organic matter (including fossil fuels like oil or gas) is burned. Carbon dioxide acts as a greenhouse gas, trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere. Plants convert carbon dioxide into oxygen during photosynthesis, the process they use to make their own food.

compound (often used as a synonym for chemical) A compound is a substance formed from two or more chemical elements united in fixed proportions. For example, water is a compound made of two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom. Its chemical symbol is H2O.

exoplanet A planet that orbits a star outside the solar system.

galaxy A massive group of stars bound together by gravity. Galaxies, which each typically include between 10 million and 100 trillion stars, also include clouds of gas, dust and the remnants of exploded stars.

Goldilocks zone A term that astronomers use for a region out from a star where conditions there might allow a planet to support life as we know it. This distance would be not too close to its sun (otherwise the extreme heat would evaporate liquids). It also can’t be too far (or the extreme cold would freeze any water). But if it’s just right — in that so-called Goldilocks zone — water could pool as a liquid and support life.

graduate school Programs at a university that offer advanced degrees, such as a Master’s or PhD degree. It’s called graduate school because it is started only after someone has already graduated from college (usually with a four-year degree).

Jupiter (in astronomy) The solar system’s largest planet, it has the shortest day length (10 hours). A gas giant, its low density indicates that this planet is composed of light elements, such as hydrogen and helium. This planet also releases more heat than it receives from the sun as gravity compresses its mass (and slowly shrinks the planet).

mass A number that shows how much an object resists speeding up and slowing down — basically a measure of how much matter that object is made from. For objects on Earth, we know the mass as “weight.”

methane A hydrocarbon with the chemical formula CH4 (meaning there are four hydrogen atoms bound to one carbon atom). It’s a natural constituent of what’s known as natural gas. It’s also emitted by decomposing plant material in wetlands and is belched out by cows and other ruminant livestock. From a climate perspective, methane is 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide is in trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere, making it a very important greenhouse gas.

molecule An electrically neutral group of atoms that represents the smallest possible amount of a chemical compound. Molecules can be made of single types of atoms or of different types. For example, the oxygen in the air is made of two oxygen atoms (O2), but water is made of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom (H2O).

Neptune The furthest planet from the sun in our solar system. It is the fourth largest planet in the solar system.

Nunavut A region of mostly frozen, snow-covered land in northern Canada. It separated from the nation’s Northwest Territories in April 1999, becoming the newest Canadian territory. It runs from Baffin Bay and the Labrador Sea in the east to the Northwest Territories in the West. It sits north of the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Comprising almost 20 percent of Canada, it is bigger than the U.S. state of Alaska, yet had fewer than 25,000 inhabitants when it was established. Most of those are native peoples, known as Inuit. Nunavut means “our land” in the Inuit language.

PhD (also known as a doctorate) A type of advanced degree offered by universities — typically after five or six years of study — for work that creates new knowledge. People qualify to begin this type of graduate study only after having first completed a college degree (a program that typically takes four years of study).

planet A celestial object that orbits a star, is big enough for gravity to have squashed it into a roundish ball and it must have cleared other objects out of the way in its orbital neighborhood. To accomplish the third feat, it must be big enough to pull neighboring objects into the planet itself or to sling-shot them around the planet and off into outer space. Astronomers of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) created this three-part scientific definition of a planet in August 2006 to determine Pluto’s status. Based on that definition, IAU ruled that Pluto did not qualify. The solar system now consists of eight planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

sodium A soft, silvery metallic element that will interact explosively when added to water. It is also a basic building block of table salt (a molecule of which consists of one atom of sodium and one of chlorine: NaCl).

spectrograph An instrument used to record light and separate it into its spectrum.

spectrometer An instrument used by chemists to measure and report the wavelengths of light that it observes. The collection of data using this instrument, a process is known as spectrometry, can help identify the elements or molecules present in an unknown sample.

spruce Any of several dozen species of coniferous evergreen tree.

sulfur A chemical element with an atomic number of 16. Sulfur, one of the most common elements in the universe, is an essential element for life. Because sulfur and its compounds can store a lot of energy, it is present in fertilizers and many industrial chemicals.

telescope Usually a light-collecting instrument that makes distant objects appear nearer through the use of lenses or a combination of curved mirrors and lenses. Some, however, collect radio emissions (energy from a different portion of the electromagnetic spectrum) through a network of antennas.

terrestrial Having to do with planet Earth. Terra is Latin for Earth.

transit (in astronomy) The passing of a planet across the face of a star, or of a moon or its shadow across the face of a planet.

wavelength The distance between one peak and the next in a series of waves, or the distance between one trough and the next. Visible light — which, like all electromagnetic radiation, travels in waves — includes wavelengths between about 380 nanometers (violet) and about 740 nanometers (red). Radiation with wavelengths shorter than visible light includes gamma rays, X-rays and ultraviolet light. Longer-wavelength radiation includes infrared light, microwaves and radio waves.

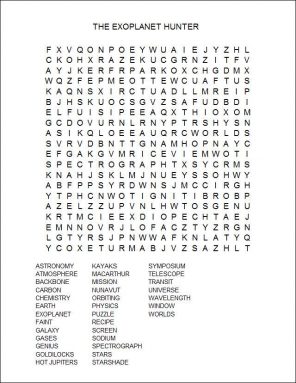

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)