Puberty may reboot the brain and behaviors

It can reshape responses to stress in children who faced trauma early in life

Puberty might help teen bodies erase the effects of childhood stress.

Katty Huertas

A preschooler slips stickers under some of the colored cups on a lazy Susan tray, then gives the tray a whirl. When the spinning stops, the child must find the hidden stickers. Most kids remember where they are. But a few have to check every single cup.

This game tests working memory — the brain’s system for storing and retrieving recent information. It’s among a set of mental skills known as executive function. These skills develop poorly in young kids who face trauma, such as physical abuse or neglect. From then on, throughout life, the body’s systems tend to respond differently, observes Megan Gunnar. She’s a child psychologist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

A childhood filled with hardship, negligence or abuse can skew the system that regulates how the body responds to stress. Problems in this stress response set kids on a path toward behavior struggles. As they grow up, these kids also face an elevated risk for depression, diabetes and a host of other health problems.

But that difficult future may not be set in stone. Stress responses can return to normal during puberty, Gunnar and others have shown. This raises the prospect that some impacts of early trauma can be erased.

The new research is prompting a rethink of puberty. It’s not just a time of acne, armpit hair and other uncomfortable body changes. Puberty also may be a window of opportunity. It could be when kids who got a difficult start get a chance to reset how their bodies respond to stress.

Surprised by stress

When the brain perceives a threat — an angry family member, a stressful exam, a high-stakes competition — levels of a hormone shoot up. Called adrenaline (Ah-DREN-uh-lin), this chemical sets off what is known as the “fight-or-flight” reaction. Breathing and heart rate soar. Palms get sweaty. Sight and other senses sharpen. Soon the brain releases chemical messengers. They go to the kidneys. This stimulates the nearby adrenal glands to release another hormone. It’s called cortisol.

Cortisol moves sugars into the blood for quick energy. It slows digestion and immune responses. It also slows growth and other processes considered nonessential in a fight-or-flight situation.

When the threat passes, adrenaline and cortisol levels fall. The heart’s rate slows. Other systems resume business as usual. The stress response turns off.

By the time Gunnar started work on her PhD in the 1970s, researchers had mapped out the key actors in this process. These signals form the HPA axis. Those letters stand for the three hormone systems that work together here: hypothalamic (Hy-poh-thah-LAM-ik), pituitary (Pih-TOO-ih-tair-ee) and adrenal (Ah-DREE-nul). Gunnar set out to study how the HPA axis influences the brain and behavior in people.

Studies in rodents and monkeys had shown that adversity early in life throws the HPA axis off-kilter. These types of studies weren’t easy. To measure cortisol, scientists had to collect blood or urine. Then methods were developed for measuring cortisol from samples of saliva. That was a lot simpler to get.

In the mid-1980s, Gunnar studied this neuroendocrine system in newborns. She showed that having a secure parent relationship regulates the system. It helps babies deal with stressful situations, such as getting vaccines. “You can go to the doctor as a baby and get a big shot in one leg and the other leg and you’re crying your head off … but [the HPA axis] doesn’t kick off,” notes Gunnar. But if babies get separated from their parents for even a few minutes, “their HPA axis shoots up like a rocket.”

Setting off this system once in a while isn’t harmful. It’s what helps us learn to cope with stress. But what if that sense of safety is disrupted for far longer?

To find out, Gunnar and a research team ventured to eastern Romania in Europe during the mid-1990s. For decades, thousands of Romanian children had grown up in orphanages. Conditions there often were crowded and grim. “You walk into these wards, and all of a sudden you’re mobbed by kids saying ‘mama, mama, mama’ — and reaching their arms up to get held,” recalls Gunnar. She had two school-aged sons at the time. “It was awful. I just wanted to bring them all home.”

Teen-time shift

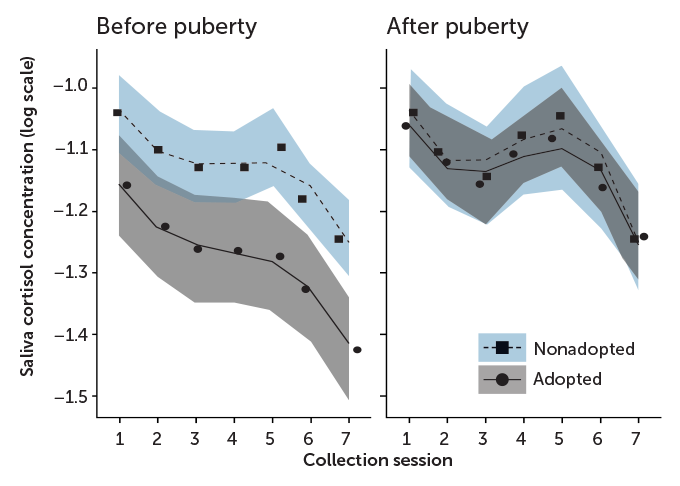

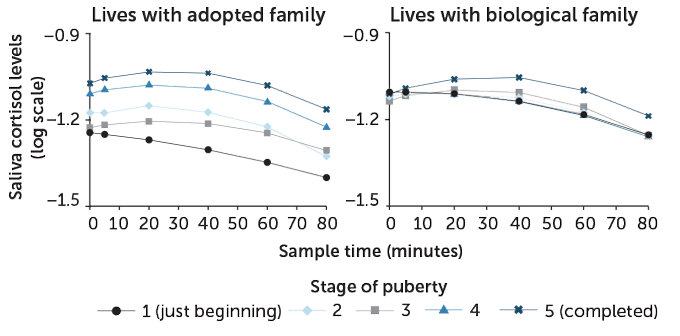

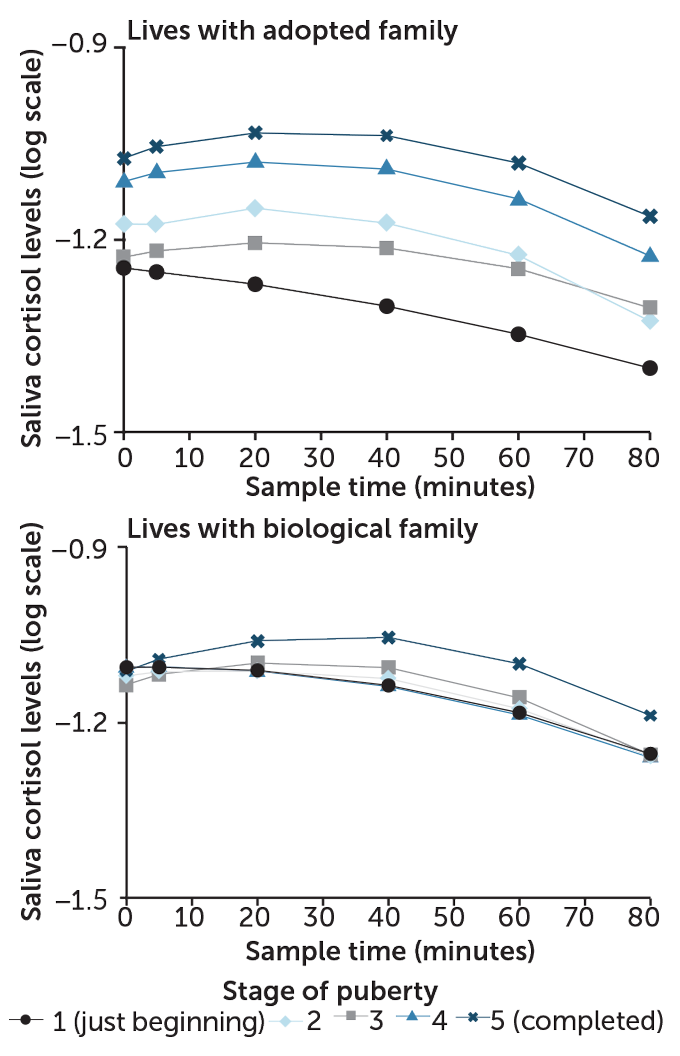

Before puberty, adopted children, who grew up with early-life trauma (gray curve), had blunted stress responses relative to kids living with biological parents (blue curve). By the time puberty ended, the adopted children showed normal cortisol patterns before, during and after a stressful task. Saliva was collected 20 minutes and 5 minutes before the task. It was then collected 5, 20, 40, 60 and 80 minutes after the task. The researchers converted the data to a logarithmic scale, which shows negative numbers. The actual cortisol levels are between 0 and 1 micro-grams per deciliter.

Cortisol stress in adopted and nonadopted children

Source: C.E. DePasquale, B. Donzella and M.R. Gunnar/J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019

What she did bring back to Minnesota, along with that searing memory, was a set of small vials. Each held a sample of saliva from one of the 2- and 3-year-old orphans. Cortisol is the end product of the neuroendocrine cascade. So measuring the children’s cortisol offered a window into the stress effects of their parental deprivation.

Analyses like these are tricky. Whether a kid faces poverty or neglect, “the way you start out in life tends to continue,” Gunnar says. A report published last November by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention points to those long-term consequences. People who experienced childhood trauma are more likely to smoke or drink heavily, it found. These people are more likely to drop out of high school. They also develop heart disease and a host of other chronic conditions at higher rates.

This doesn’t mean that having a completely smooth life is good. Growing research suggests that some adversity — such as dealing with a bad grade or a challenging friendship — can help a child build resilience. And there may be a sweet spot for how much hardship brings this benefit without becoming overwhelming (see sidebar).

Adoptee struggles

Early-life hardship clearly takes a toll. To study these effects, Gunnar needed children who had felt deprivation in infancy, then moved into healthy, supportive homes. Such children, she reasoned, would be the ideal human analog for all of the animal studies on early adversity. It dawned on her that such a group exists. They are adopted children who spent part of their early life at an orphanage.

Gunnar shared her idea with members of the adoption unit at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This group provides services to improve the health and well-being of Americans. With their support and funding, she surveyed parents who between 1990 and 1995 had adopted children from other countries. She also invited Minnesota families with adopted children to join a university registry and to take part in her research.

Parents noticed early on that often their adopted kids had behavioral problems. They brought the children to the university lab for problem-solving and sorting tests. These included that lazy Susan task and the famous marshmallow test of delayed gratification. (In the marshmallow test, experimenters offer young children either one small reward right away, such as a marshmallow, or two small rewards if the kids wait 15 minutes. Follow-up research suggested that preschoolers who held out for the larger reward had healthier behaviors and years later showed better success in school.) In such tests, adopted kids struggled with attention and self-regulation.

Much to the researchers’ surprise, the kids also had unusually low cortisol levels. In the face of sustained hardship, cortisol levels usually skyrocket. But high cortisol is bad for the body. It can raise a person’s risk for various conditions, including heart disease and diabetes. So a weak stress response could be “nature’s way of preserving the brain and body,” Gunnar now speculates.

She continued studying the Minnesota adoptees as they grew older. Preschoolers with low cortisol often entered kindergarten with attention problems. They might also show problem behaviors, such as physical aggression and cheating. Their blunted stress responses persisted, too. They lasted even after the kids had spent an average of seven to eight years in a caring adopted family.

That was disheartening, says Russell Romeo. He works at Barnard College of Columbia University in New York City as a psychobiologist. “We’d always thought that maybe if these individuals get out of the adverse situations, they could start recalibrating their stress reactivity.”

But earlier work that Romeo had done in the mid-2000s gave Gunnar reason to think she just needed to study the children longer.

High time for change

Romeo had been studying rats. He wanted to see if stress affects the brains of adolescents and adults differently. In one set of experiments, he stressed the animals by trapping them inside a wire-mesh container for 30 minutes. Some rats were adults. Others were young and had not yet undergone the rat version of puberty. Romeo measured levels of the rat’s version of cortisol. He recorded levels before, during and after their confinement. The stress spiked hormone levels in both age groups similarly. But levels in the young rats took far longer to get back to normal.

Then Romeo observed how the animals reacted to repeated periods of stress. The rats endured the 30-minute restraint each day for seven days. Now the stress pattern changed. On the first day, stress hormones surged higher in young rats than in adults. But at the end of the seven days, rats near puberty returned to their initial levels more quickly. The responses were being shaped more powerfully when those stressors occurred around puberty rather than later in life. This suggests that puberty may offer a greater potential for change.

Other researchers studied what happens when adolescent rats move into “enriched” environments. These were larger cages with more toys and cage-mates. It was the rodent equivalent of a human’s nice home and family. A nicer environment could reset to normal the stress responses that had been thrown out of whack by early-life trauma, these studies showed.

Those findings heartened Gunnar. “Maybe I should be looking at puberty,” she thought. It could be a time to recalibrate.

So her team invited 280 children into the lab to complete two stressful tasks. All were 7- to 14-year-olds. They included 122 children adopted from institutions. Another 158 kids had not been adopted but came from families of similar backgrounds.

For the first test, each of the children prepared a 5-minute speech introducing themselves to a new class of students. They gave the speech facing a video camera and a mirror. Their speech would be rated by judges, they were told. Some kids spoke with confidence. Others looked nervous. “We did have one who burst into tears,” Gunnar says. But “we don’t torture them. If we think they’re too nervous, we help them quit.”

After the speech, participants spent five minutes on a verbal subtraction task. The difficulty was adjusted by age. Seven- and 8-year-olds began with the number 397 and counted down by 3s. Kids 11 and older started with 758 and subtracted by 7s.

Before and after these tasks, researchers collected saliva from each child to measure cortisol levels. The researchers also noted at what stage of puberty each child was in —from 1 to 5. Stage 1 meant no noticeable body changes. At stage 5, a child had completely matured physically.

Among kids in early puberty (stage 1 and 2), adopted kids had lower cortisol levels than did children living with their biological parents. This confirmed Gunnar’s previous research on Romanian orphans and international adoptees living in the United States. Trauma showed an effect on those kids.

In the late-puberty group (stages 3 to 5), however, cortisol patterns looked similar for adopted and non-adopted kids. The adopted kids appeared to have gotten over the impacts of their earlier trauma.

Rather than just comparing across groups, Gunnar and her colleagues wanted to confirm that a normalizing of the HPA axis had occurred in each of the kids. So they brought these children back for the same tests one and two years later (for a total of three yearly sessions).

Closer to normal

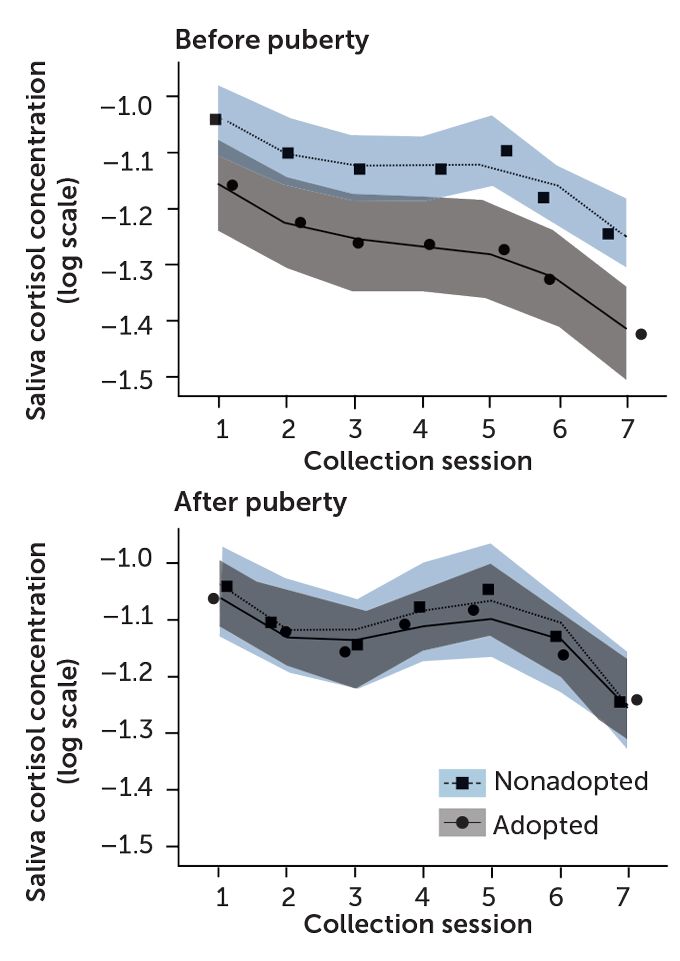

During a stressful activity (giving a speech, for example), saliva cortisol levels rose temporarily and returned to normal in those children who lived with their biological parents. Children who were adopted after starting life in an orphanage (an early-life trauma), had blunted cortisol responses during stages 1 to 2 of puberty. But at the tail end of puberty, stages 4 and 5, adopted children’s stress responses normalized.

Stages of puberty and cortisol stress reaction

Source: M.R. Gunnar et al/PNAS 2019

The body recalibrates its response to stressors during puberty, they found.

Says Romeo, this may mean the teen brain responds better to interventions that didn’t work during childhood.

Gunnar’s team detailed its findings November 26, 2019 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Matthew Duggan is a therapist in Long Beach, Calif. He finds the new results encouraging. They could apply, he thinks, to a range of children who have trouble managing their emotions and connecting with others because caretakers abused or ignored them at a young age.

There may be “a window, you know, a decade from now, where things might be able to change,” Duggan says. “And we have some data here to suggest that at a biological level, that is a possibility. For me, that’s really hopeful to see.”

How might puberty combine with better caregiving and support to reshape the body’s response to stress? One speculation stems from the fact that brain regions controlling how we react to stress are among ones that continue to mature during adolescence. So there might be some brain flexibility that “lends itself to changes uniquely during this time,” Romeo says.

Mental health and resilience emerge from an ever-changing mix of genes and life experiences. Some of these set the body awry early on. But research by Gunnar and others shows that adolescence could potentially erase some of the damage. And future work could reveal more of the underlying biology behind such a reboot.

This story was produced with support from the D.H. Chen Foundation.