Pythons seem to have an internal compass

The giant, invasive snakes living in Florida’s Everglades like their new home — and will return to it if people try to move them somewhere else

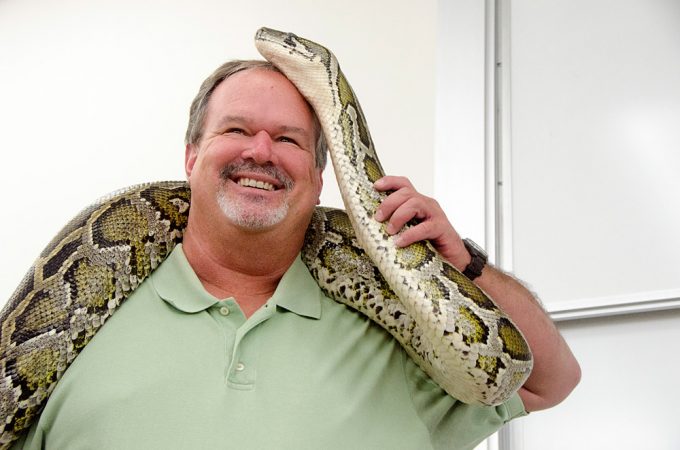

Many thousands of Burmese pythons, like this one, are now living — and reproducing — in the Florida Everglades.

Everglades National Park

By Susan Milius

Burmese pythons need no GPS to find their way home. Although native to Asia, these snakes have been let loose in South Florida. There they have settled in and begun reproducing. And reproducing. And then reproducing some more. Today, scientists believe tens of thousands of these giant snakes call the Everglades National Park home. But take them away and they may just come back. New research finds these giant snakes are unexpectedly good at returning home.

Since at least 1995, the snakes (Python molurus bivittatus) have been breeding in the Everglades. And for nearly as long, people have worried about how to get rid of them. The pythons can grow to 5.5 meters (18 feet) long. And they are strong enough to tangle with alligators. They can survive a year without eating. But when hungry, they will eat any of many small mammals including the endangered Key Largo woodrat. They can even swallow the occasional adult deer.

A study has now probed how well pythons navigate their landscape. Researchers captured six adult pythons in the Everglades and trucked them 21 to 36 kilometers (13 to 22 miles) away. There they released the snakes and tracked their travels.

All but one managed to get back to within 5 kilometers (3 miles) of their starting locations, notes Shannon Pittman. She’s a post-doctoral scholar at Davidson College in North Carolina. There she works with snake-conservation scientist Michael Dorcas, a Burmese python expert.

The snakes’ ability to navigate doesn’t look good for efforts to contain them, Pittman says. Since pythons seem to have a good sense of where they are, they may take risks to explore new habitats or venture to far-off hunting areas. After all, it now seems unlikely that they will get lost.

Few studies have looked in detail at navigation in snakes. Sea kraits have shown homing powers. Researchers studied them in the waters of the archipelago nation of Fiji. When moved from their home island to another about 5 kilometers away, the kraits returned home again. However, when timber rattlesnakes and Aruba rattlers were captured and moved, these snakes showed no similar ability to find their way back.

Tagging kept an ‘eye’ on the travelers

To test the Everglades pythons, Pittman and her co-workers caught 12 adults. They drove them in covered containers to a wildlife center. There the researchers implanted radio transmitters — a type of radio-taggingtechnology — into the animals. Why? The splotchy brown snakes are “secretive,” Pittman explains. “You can be right beside a 10-foot snake and not see it.” But with the tags, her team can follow even camouflaged snakes.

The biologists returned six pythons to where they had been captured. They drove the rest to new patches where pythons are known to flourish.

The snakes slithered widely. And the terrain they traveled was so difficult that the researchers often had to track signals from the pythons’ radio-tagging gear using a small, low-flying plane.

Snakes that had been trucked far away moved faster and along straighter homeward paths than did the put-back-in-place snakes. Pittman now would like to know how younger snakes behave. After all, they’re the ones that need to seek new homes.

How pythons steer their course isn’t clear, Pittman says. She notes, however, that some reptiles can sense Earth’s magnetic field, solar cues, odors — even polarized light. Pythons might rely on these, plus landmarks, to get back home.

In the Everglades, which remains warm year-found, pythons don’t have to find a den to hide in for safety during the winters. That’s why snake ecologist Howard Reinert of the College of New Jersey in Ewing finds it “a bit surprising” these pythons would be so motivated to get back home. He’d like to know more about whether pythons that were not trucked far from home also seemed similarly attached to their homes.

Power Words

archipelago A group of islands, many times forming in an arc across a broad expanse of the oceans. The Hawaiian islands, the Aleutian islands and the more than 300 islands in the Republic of Fiji are good examples.

conservation The act of preserving or protecting the natural environment.

ecology A branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings. A scientist who works in this field is called an ecologist.

Everglades Short for Everglades National Park, this site was established in 1947 as a federally protected wetlands area. At almost 2,500 square miles (6,070 square kilometers) in size, it is the largest subtropical wilderness in the United States. Owing to its unique nature, it is also considered a World Heritage Site. Best known for its alligators, this park is almost gaining notoriety as the home for several reproducing species of alien giant snakes, most notably the Burmese python.

global positioning system Best known by its acronym GPS, this system uses a device to calculate the position of individuals or things (in terms of latitude, longitude and elevation — or altitude) from any place on the ground or in the air. The device does this by comparing how long it takes signals from different satellites to reach it.

habitat The area or natural environment in which an animal or plant normally lives, such as a desert, coral reef or freshwater lake. A habitat can be home to thousands of different species.

navigate To find one’s way through a landscape using visual cues, sensory information (like scents), magnetic information (like an internal compass) or other techniques.

postdoctoral scholar (or post-doc) A research position for people who have just completed their doctorate in some field of study. It allows the individual to acquire new skills or pursue new lines of research on the road to a research career.

python A large, heavy-bodied, nonpoisonous constrictor snake.

sea krait A very venomous snake that spends most of its like at sea. It comes on land largely to drink fresh water or reproduce.

tagging (in biology) Attaching some rugged band or package of instruments onto an animal. Sometimes the tag is used to give each individual a unique identification number. Once attached to the leg, ear or other part of the body of a critter, it can effectively become the animal’s “name.” In some instances, a tag can collect information from the environment around the animal as well. This helps scientists understand both the environment and the animal’s role within it.

terrain The land in a particular area and whatever covers it. The term might refer to anything from a smooth, flat and dry landscape to a mountainous region covered with boulders, bogs and forest cover.