Creation of quantum dots wins 2023 chemistry Nobel

These nanosize specks are now used in a huge range of tech — from TVs to medical tools

Shining ultraviolet light on these liquids causes them to glow different colors, thanks to quantum dots of different sizes.

Tayfun Ruzgar/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Carolyn Gramling and Tina Hesman Saey

Listen to this story:

Have feedback on the audio version of this story? Let us know!

Typically, matter made of the same kinds of atoms arranged in the same way has the same properties. But tiny specks called quantum dots are special. They can contain the same molecules yet have different colors and other qualities depending on their size. The ability to make a whole rainbow of quantum dots simply by tweaking their size makes the dots highly useful. They light up TV screens and help doctors see inside the body. Now, the 2023 Nobel Prize in chemistry honors three scientists who discovered and created quantum dots.

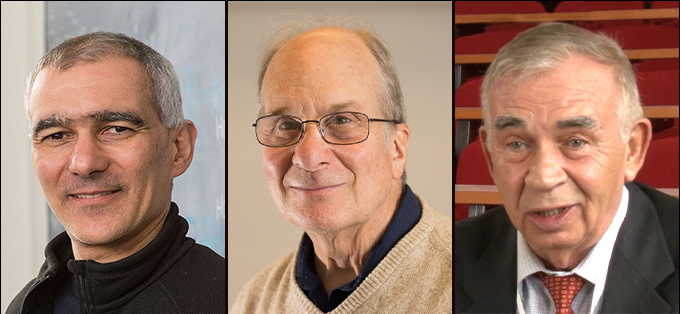

One of those scientists is Moungi Bawendi. He’s a chemist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge. The second winner is chemist Louis Brus. He’s based at Columbia University in New York City. The final winner is Alexei Ekimov. This physicist now works at Nanocrystals Technology, Inc., in Briarcliff Manor, N.Y.

The trio will split a prize of 11 million Swedish kronor, or about $1 million. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced the honor October 4.

A new kind of material

“Quantum dots are a new class of materials, different from molecules,” said Heiner Linke. A member of the Nobel committee, he spoke at the award announcement.

Quantum dots are each a few billionths of a meter across. At such a tiny scale, their qualities are governed by the weird laws of quantum mechanics. Those quantum laws rule that changing the dots’ size alters their properties. That includes how the dots interact with light and electricity. It also includes their magnetic properties and at what temperature they melt.

One useful quality that changes with a quantum dot’s size is its color. Usually, “if you want to make different colors with molecules, you would choose a new molecule,” Linke said. That is, a new set of atoms arranged in a different structure.

But changing a quantum dot’s size can change its color without changing its molecules. Quantum dots give off fluorescent light of different colors when they are bathed in laser light. Smaller dots give off bluer light. Bigger dots give off redder light.

Dots of the same size made from different materials may give off slightly different colors. Quantum dots are usually made from semiconductors. Such materials include graphene, selenite or metal sulfides. By adjusting the sizes and materials of quantum dots, chemists can alter their properties for a huge range of uses.

Possible after all

Scientists suspected that nanoparticles’ sizes could alter their properties nearly a century ago. But at the time, it seemed impossible to actually make such particles. To do that, researchers would need a material with a perfect crystal structure. They’d also have to be able to control the size of that tiny speck extremely precisely. So precisely, in fact, that they’d have to sculpt the particle one layer of atoms at a time.

Then, in the early 1980s, Ekimov and Brus each showed this could be done. The two did not work together. Ekimov created quantum dots with glass. Adding copper chloride to the glass produced tiny crystals. Ekimov then showed that the size of those crystals was linked to the color of the glass.

Brus made a similar discovery. He showed that there was a link between size and color for nanosize particles floating in a solution or in a gas.

Those discoveries stirred up intense interest in how such dots could be used. But making quantum dots for specific uses would require precisely controlling the dots’ size.

A decade later, Bawendi devised a method to do just that. His technique allowed him to stop the growth of tiny crystals in a solution when they reached a desired size. Here’s how it worked. He first injected chemicals into a solution that instantly formed tiny crystals. Then, he tweaked the temperature of the solution to halt the crystals’ growth.

“I’m deeply honored and surprised and shocked by the announcement this morning,” Bawendi said October 4. He spoke at an MIT news conference. “I’m especially honored to share this with Lou Brus,” Bawendi said of his mentor. “I tried to emulate his scholarship and his mentoring style as a professor myself when I came to MIT.”

Bawendi started working on quantum dots after meeting Brus. The two worked at Nokia Bell Labs, headquartered in Murray Hill, N.J. There, researchers needed high-quality quantum dots to study the physics of nanoparticles.

“It wasn’t because I wanted to make the best quantum dots possible for application,” Bawendi said. “It was because we needed to make the best possible quantum dots to study them.” It took years of trial and error to work out the method.

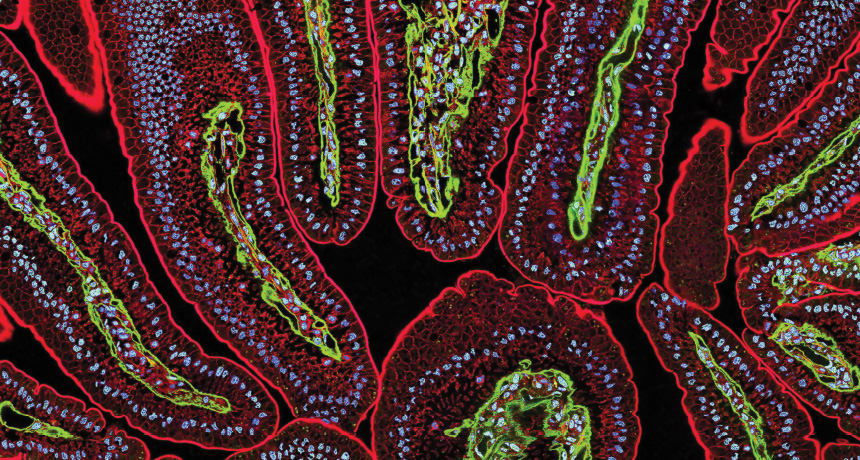

Provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific. Image by Thomas Deerinck and Mark Ellisman/National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

Applications abound

Bawendi’s work made it possible to manufacture quantum dots with specific sizes — and therefore specific properties. This opened up a world of possible uses for the dots.

For one thing, quantum dots can be used to subtly change the color of LED lights. This can dramatically improve the lights’ energy efficiency.

Quantum dots are also useful in medicine. They can be injected into the body and attached to cells from the body’s immune system. Such cells swarm cancerous tissues. By tagging the cells with fluorescent quantum dots, surgeons can spot even hard-to-see tumors inside the body.

Quantum dots can also be tuned to absorb different colors of light. So they could be used to build solar panels that soak up sunlight well in different conditions. The dots may even be used to build quantum computers. Such computers promise to run much faster than any normal computer ever could.

This year’s chemistry Nobel is well-deserved, says Warren Chan. He’s a biomedical engineer and chemist at the University of Toronto in Canada. “They’re the ones who built the foundation,” Chan says of the winners. “I’m really happy that the field is getting credit for really changing the world.”

Chan and his colleagues found one of the first uses for quantum dots in the 1990s. Their group used quantum dots to tag cells in lab experiments. But the Nobel committee doesn’t just look at past impacts of a discovery, Chan notes. They also consider the effects a discovery may have in the future. And quantum dots could have a whole medley of uses not yet explored. Chan’s team, for instance, is now using quantum dots to detect infections such as flu and HIV.

“I was absolutely thrilled to see this,” says Judith Giordan. She’s the president of the American Chemical Society. “We have three people recognized who brought this technology from a dream, a hope, a theoretical construct … all the way through synthesis and manufacture.”