Suffering from racist acts can prompt Black teens to constructive action

Racism hurts teens. A new study shows how teens empower themselves to fight back

Black teens experience a lot of racism. A new study shows that stress from such experiences leads some to call out the problem as a step toward getting rid of racist systems.

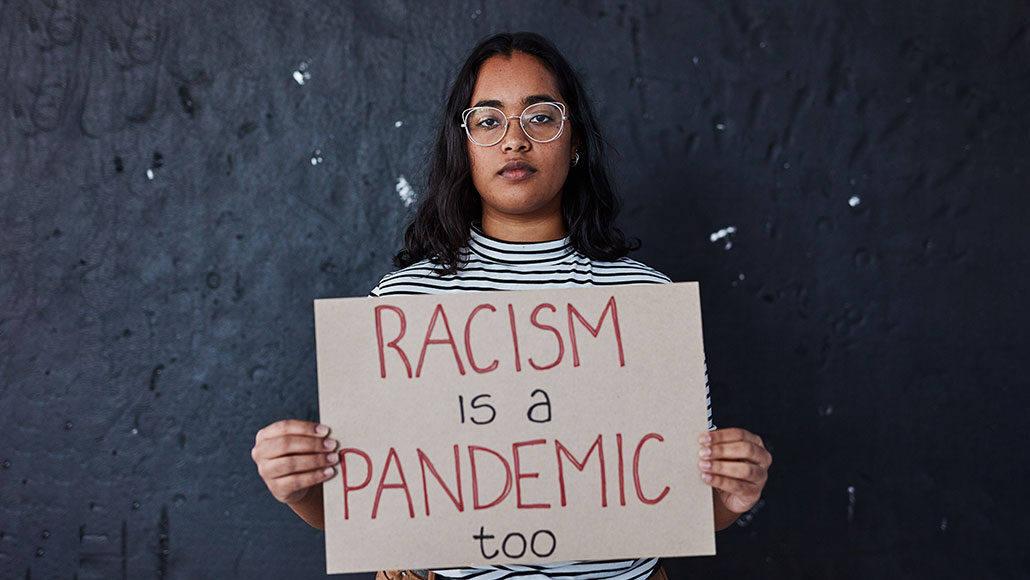

LumiNola/E+/Getty Images

Black teens in the United States encounter racism almost every day. Many teens recognize that racist acts and experiences have been a fixture of American society since before the United States was even its own country. But as Black teens think about and understand racism today, they might find their own resilience as well — and begin to fight for social justice. That’s the finding of a new study.

In the face of a negative and unjust system, the study now reports, some teens actually found resilience.

Most people think of racism as a social issue. But it’s a health issue, too. Being confronted with racist acts can hurt a teen’s mental health. It can make people question their self-worth. Scientists have even linked signs of depression in Black adolescents to their experiences with racism.

Racism isn’t just a momentary encounter, Nkemka Anyiwo points out. She works at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. As a developmental psychologist, she studies how the mind can change as people grow up. Black people feel the effects of racism constantly, she says.

Black teens also have seen or heard about people who look like them that have been killed by police. The recent deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd received national attention during the summer of 2020. In fact, each death fueled massive protests for racial justice.

And these were not isolated examples. Black people have been suffering from race-based violence “since the beginning of America,” Anyiwo notes. Racism is “the lived experiences of people across generations.”

Elan Hope wanted to know how teens react to ongoing racism. She works at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. As a psychologist, she studies the human mind. In 2018, Hope decided to ask Black students across the United States about their experiences with racism.

The many faces of racism

Teens might experience different types of racism. Some experience individual racism. Perhaps white people stared at them with hostility, as though they did not belong. Maybe someone called them a racial slur.

Others experience racism through institutions or policies. For example, they might be walking through an area where mostly white people live and get questioned by white people about why they are there. This might happen even when the Black teen lives in that neighborhood.

Still others experience cultural racism. This may show up in media reports. For instance, Hope notes, when the news reports a crime, there’s often “a focus on negative attributes if it’s a Black person.” Perhaps the Black teen will be described as having a “dark past.” In contrast, a white teen who commits a crime might be described as “quiet” or “athletic.”

Hope and her colleagues asked 594 teens between the ages of 13 and 18 whether specific acts of racism had happened to them within the past year. The researchers also asked the teens to rate how stressed they were by those experiences.

On average, 84 percent of the teens reported they had experienced at least one type of racism in the past year. But when Hope asked teens if experiencing such racist things bothered them, most said it had not stressed them much. They seemed to brush it off as just how things are, Hope says.

Maybe some teens experience racism so often that they cease to notice each instance, Anyiwo says. She points to one study in which Black teens kept a diary of their experiences. The kids encountered an average of five racist incidents per day. “If you’re experiencing discrimination that frequently there might be a numbness,” she says. “You may not be [aware] of how it impacts you.”

And that may partly explain why 16 percent of teens in the new study by Hope’s group reported experiencing no racism. These teens were asked to recall events, Anyiwo says. And younger teens, she notes, might not have realized that some of the things they experienced had been triggered by someone’s response to their race.

But not all of the teens that Hope’s group surveyed felt so calm about it. To some, the pain or injustice “really did hit home.”

Moved to act

Systemic racism is a type that is baked deeply into a society. It’s a series of beliefs, norms and laws that privilege one group over another. It can make it easier for white people to succeed, but harder for people of color to get ahead.

People participate in and sometimes contribute to systemic racism all the time, even when they don’t realize it. It’s there in the different schools and educational resources to which students have access. It’s in the different places people are able to live and the way job opportunities are not equally available to all people.

Racism also is there in the way people act. Some may refer to Black teens with racial slurs. Teachers and school officials might punish Black students more often and more harshly than white students. Store workers might follow Black kids around and baselessly suspect them of stealing — just because of the color of their skin.

Racism comes in non-physical forms, too. People might value the work of Black teens less. They might question their intelligence more. Black teens often have less access to advanced high-school courses that might help them succeed in college. Teachers may even steer them away from taking such classes.

Hope’s team looked at whether stress was linked to how teens thought, felt and acted in the face of racism. In the surveys these teens took, each rated statements on scales of one (really disagree) to five (really agree). One such statement: “Certain racial or ethnic groups have fewer chances to get good jobs.”

The statements were designed to measure whether the teens were thinking of racism as a systemic issue. Finally, the scientists asked the teens if they themselves had taken any direct action against racism.

The more stressed that teens said they were by the racism they experienced, the more likely they were to have participated in direct actions to fight it, the new study found. Those acts might have included going to protests or joining anti-racist groups. Teens stressed by racism also were more likely to think deeply about racism as a system and to feel empowered to make a difference.

Hope and her colleagues shared what they learned in the July-September Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology.

Teens take action in their own way

The connection between stress and action was fairly small, Hope says. But “there is a pattern” of kids who are stressed by racism beginning to see that it is all around them. And some begin to fight that system.

Other things might have affected the findings, too. Many parents might not let their kids attend protests, for instance. And people who are especially involved in their communities might be more likely to join protests. It could be that many teens who want to take action have not done so yet.

And taking action does not always mean protesting, Hope points out. It could amount to wearing t-shirts with anti-racist messages, such as “Black Lives Matter.” Or students might have started “confronting friends who make racist jokes.” They could also be posting about racism online. These are “actions that youth can take that are less risky,” she says.

Many scientists study how racism affects teens. But unlike here, most others have not studied what the teens might do in response to racism, says Yoli Anyon. She’s a social worker, someone trained to help people cope with challenges. Anyon works at the University of Denver in Colorado. “We always worry if you expose young people to indicators of oppression, like racism, it can be disempowering,” she says. Stress — including the stress from racism — can lead to symptoms of anxiety and depression.

But this study shows that stress from racism can lead some teens to see the systemic racism around them clearly. “It’s evidence that even at a young age, youth are able to detect and understand their experiences of racism and potentially connect that to issues of inequality,” Anyon says. “I think adults tend to overlook young people’s knowledge and insight and the degree to which they are experts in issues like this.”

Adults might have something to learn from these kids, too, Anyon says. Teens could help shape what the future of protest looks like. “It doesn’t have to be the same action [that was] taken in the past,” she says. “Especially in the time of COVID-19, we all have to find new ways of taking action.” Teens use hashtags, apps and others methods to pursue racial justice. “We as adults need to listen to them.”