Record Ebola epidemic strikes

Nearly 1,000 people in West Africa have died from the disease, which may have been triggered by eating wild animals

A nurse in Monrovia, Liberia, washes her hands after treating a patient with Ebola. Unlike urban U.S. hospitals, many clinics caring for Ebola patients in Africa lack the spacesuit-like protective gear for their staff. And that explains why health-care workers can face a high risk of becoming infected.

BethanyFank/iStockphoto

Ebola, a deadly viral infection, has been circulating throughout three West African nations since last December. Its formal name, Ebola hemorrhagic fever, says it all. The disease triggers high fevers, listlessness and widespread, uncontrolled bleeding that can occur seemingly anywhere and everywhere. The virus spreads through contact with bodily fluids, especially blood. By August 6, 2014, health agencies were reporting that Ebola appeared to have sickened 1,711 people, killing 932.

In past outbreaks, the virus has killed up to eight or nine out of every 10 people who catch it.

More than half of the people sick with Ebola in Africa now have died. And the death toll is expected to climb.

There is no cure for this disease. Several vaccines are being developed. None, however, have been approved yet for use in people. Still, vaccines would likely offer little help for people who are already infected. Vaccines are designed to stimulate the body into making antibodies. Those antibodies could fight off future disease, but are unlikely to help knock out any existing infection.

For now, doctors can only make infected people as comfortable as possible. Soon, however, medicines may be available to treat people sick with Ebola. One of them is a drug consisting of pre-made antibodies.

This past January, Mapp Biopharmaceutical Inc. identified a combination of three antibodies from mice that might work as a drug to treat people who already have Ebola. The company has begun using plants to copy the antibodies. To date, it has made only a small amount of the prototype drug, which it calls ZMapp. It was supposed to be used in upcoming animal tests.

The San Diego-based Mapp has been working with a number of partners, including the U.S. and Canadian governments. To date, Mapp says, it has not yet gotten approval to use the drug on people. The patients in Africa volunteered to take it anyway, before being flown back to the United States. Both patients arrived within the past six days and are now being cared for at a high-security facility. It’s at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Ga. This hospital has a special section available to care for people with such highly infectious and deadly diseases. Health officials have said both patients seemed a bit better after getting the Zmapp, although both remain critically ill.

That encouraging news has led some people to ask whether more of the drug can’t be rushed into production. But many health-care agencies are uncomfortable with offering an unproven drug to people. It could be dangerous. It may not work (things that work in animal studies often don’t help people). However, doctors also realize that when infected people are likely to die, most will accept a high degree of risk.

Even so, the experimental treatment raises problems of ethics. These are issues of whether something is moral or proper. For instance, even if the Ebola drug is safe and cures people, it will likely cost a lot of money. And Ebola is hitting people who live in poor countries. The company also cannot yet make enough of the drug to give it to everyone who would need it. So someone would have to decide who got the drug and who didn’t.

“We are in an unusual situation in this outbreak,” says Marie-Paule Kieny. An expert on viruses, she’s also the Assistant Director-General of the World Health Organization, or WHO, in Geneva, Switzerland. “We have a disease with a high fatality rate without any proven treatment or vaccine,” she notes. “We need to ask the medical ethicists to give us guidance on what the responsible thing to do is.”

So WHO has announced that on Aug. 11 or shortly after that, it will bring together a panel of ethicists to mull over the troubling issue.

The history of the latest epidemic

The new Ebola outbreak started last December. It first showed up in Meliandoua. This is a village in the rainforests of eastern Guinea. At first, no one knew the disease was Ebola. It had never been seen in this part of Africa. Its symptoms also can resemble malaria and other diseases.

Then the disease moved on and began killing people in cities. That’s highly unusual. Earlier outbreaks of this disease, which seldom struck more than 40 to 60 people, had typically showed up in rural, forested areas of Central Africa. Experts on infectious diseases are therefore puzzled: How did Ebola make its way to West Africa and then spread into cities?

The WHO issued its first alert about the emerging outbreak on March 23. As of August 6, Sierra Leone had 576 confirmed cases of Ebola this year, Guinea had 351 and Liberia had 143. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, says these numbers refer to the cases confirmed by laboratory testing. In each country, more suspected cases exist. For example, although there have been no confirmed cases in Nigeria this year, there has been one death and 8 people sickened in that nation by what appears to be Ebola.

Ebola has only been known since 1976. At that time, it stuck 318 people in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and 284 in Sudan (now South Sudan). Only a few big outbreaks — those sickening 150 to 425 people — have occurred before this year. Some of the sporadic outbreaks over the years did, however, show what appeared to be a death rate of between 70 and 89 percent.

Are bats to blame?

The perplexing question is where the disease originally came from and where it hides out. Sometimes many years have gone by between outbreaks. “Ebola is famous for disappearing back into the forest,” says Kevin Olival. He’s a disease ecologist at EcoHealth Alliance in New York City. But this year, a number of people have been pointing their fingers at fruit bats, he says.

Why bats? They have been linked to a number of diseases that have spilled over from animals into humans. Among them is Nipah virus, which killed more than 100 people in Malaysia in the late 1990s. Another is severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, which killed 774 people around the world in 2003. Then there’s Hendra virus, which emerged near Brisbane, Australia in 1994. That outbreak, which killed 14 racehorses and trainer, was the first of at least 10 Hendra outbreaks to hit that country. Bats may even be a source of Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS. Since 2012, it has sickened 721 people and killed 298 in Saudi Arabia alone.

In April, Fabian Leendertz led a 17-member team to Guinea. This disease ecologist works at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin. He wanted to find the animal reservoir of the virus responsible for West Africa’s Ebola outbreak. Reservoir is the term biologists use to describe an animal that can host a pathogen, or disease-causing organism. Because it does not usually sicken these animals, the pathogen can persist — undetected — in the reservoir animals for years. Diseases that spread to people from animals are known as zoonoses.

Even though Leendertz’s team came together quickly, “We were still three months late,” he told Science News for Students. Since the epidemic started, “Many things may have changed.”

His group collaborated with ecologists who monitor forest animals. His team also captured bats for testing. Leendertz won’t share what his team has found. But he does say there were no obvious epidemics among animals. Indeed, he adds, “We didn’t stumble across any dead animals.”

One reason fruit bats may be under the spotlight: a study published April 17 in Viruses. In it, Olival and David Hayman mapped the ranges of fruit bats that might carry Ebola or related viruses. Hayman works at Massey University in Palmerston North, New Zealand. Some bat species that dwell in Central African countries — such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire), where Ebola has appeared in the past — also can be found in West Africa, the two scientists noted.

That suggests bats could have ferried the virus across vast distances.

And in recent years people may have started interacting more with bats, Olival says. Forests in West Africa and other places are being cleared to make room for farming or building houses and other buildings. The displaced animals may roost in human houses when trees are destroyed.

A single interaction between a person and an infected bat could have triggered the 2014 Ebola epidemic, Leendertz says. Other people could have then brought Ebola out of the rainforest and into cities.

But even if that’s what happened, “The right answer is never to kill all the bats,” Olival says. That would be an ecological disaster. After all, bats devour insects and pollinate tropical plants. What’s more, bat hunts would only increase human contact with potentially infected animals.

Instead, researchers need to learn more about the environmental and biological conditions that lead to outbreaks. For instance, CDC scientists found Marburg virus — a cousin of Ebola — in bats living in caves in Uganda. That’s a nation in East Africa. These scientists showed that miners and tourists were more likely to pick up the virus during the bats’ twice-yearly birthing seasons. That, Olival says, could make avoiding a deadly hemorrhagic fever as simple as avoiding bats around the season their babies are born.

Beyond bats

It is certainly possible that bats could spread Filoviruses, the thread-shaped pathogens responsible for Marburg and Ebola infections, Olival says. Still, he charges, it is too early to tie this year’s epidemic to the flying mammals. “The evidence is scant that bats are to blame for the West African outbreak.”

Leendertz, too, thinks one bad bush-meat carcass could have sparked the current epidemic. The Guinean government declared a ban on eating bush meat at the end of March. But for some people this ban poses problems, he says. Bats, antelope, monkeys, squirrels and other creatures can be an important part of their diet.

Anyone who eats bush meat runs the risk of getting Ebola or several other diseases, he points out. And some bush meat is riskier than others. Bats, freshly dead carcasses of great apes, other primates and antelopes known as duikers are among the bush meat animals most likely to be infected with Ebola.

Power Words

antibody Any of a large number of proteins that the body produces as part of its immune response. Antibodies neutralize, tag or destroy viruses, bacteria and other foreign substances in the blood.

bat A type of winged mammal comprising more than 1,100 separate species — or one in every four known species of mammal.

bushmeat Wild mammals eaten by people, including not only cats, Chinese bamboo rats, squirrels, badgers and civets but also primates, such as monkeys, chimps and gorillas.

carcass The body of a dead animal.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC An agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC is charged with protecting public health and safety by working to control and prevent disease, injury and disabilities. It does this by investigating disease outbreaks, tracking exposures by Americans to infections and toxic chemicals, and regularly surveying diet and other habits among a representative cross-section of all Americans.

Ebola A family of viruses that cause a deadly disease in people. Most cases occur in Africa and Asia. Its symptoms include headaches, fever, muscle pain and extensive bleeding. The infection spreads from person to person (or animal to some person) through contact with infected body fluids.

ecology A branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings. A scientist who works in this field is called an ecologist.

epidemic A widespread outbreak of an infectious disease that sickens many people in a community at the same time.

epidemiologist Like health detectives, these researchers figure out what causes a particular illness and how to limit its spread.

filovirus A small family of viruses, named for their wormy, threadlike shape. To date, the only members of this family are the viruses that cause Ebola and Marburg. Both are extremely deadly infections that cause high fevers and extensive, uncontrolled hemorrhaging (bleeding).

hemorrhage (adjective is hemorrhagic) Related to major or uncontrolled bleeding, often internally.

infection A disease that can spread from one organism to another.

mammal A warm-blooded animal distinguished by the possession of hair or fur, the secretion of milk by females for feeding the young, and (typically) the bearing of live young.

Marburg A viral disease that causes a hemorrhagic fever. It’s caused by a filovirus, an infectious agent in the same family as Ebola.

pathogen An organism that causes disease.

pollinate To transport male reproductive cells — pollen — to female parts of a flower. This allows fertilization, the first step in plant reproduction.

primate The order of mammals that includes humans, apes, monkeys and related animals (such as tarsiers, the Daubentonia and other lemurs).

proteins Compounds made from one or more long chains of amino acids. Proteins are an essential part of all living organisms. They form the basis of living cells, muscle and tissues; they also do the work inside of cells. The hemoglobin in blood and the antibodies that attempt to fight infections are among the better known, stand-alone proteins.Medicines frequently work by latching onto proteins.

prototype A first or early model of some device, system or product that still needs to be perfected.

reservoir A large store of something. Lakes are reservoirs that hold water. People who study infections refer to the environment in which germs can survive safely (such as the bodies of birds or pigs) as living reservoirs.

vaccine A biological mixture that resembles a disease-causing agent. It is given to help the body create immunity to a particular disease.

virus Tiny infectious particles consisting of RNA or DNA surrounded by protein. Viruses can reproduce only by injecting their genetic material into the cells of living creatures. Although scientists frequently refer to viruses as live or dead, in fact no virus is truly alive. It doesn’t eat like animals do, or make its own food the way plants do. It must hijack the cellular machinery of a living cell in order to survive.

World Health Organization An agency of the United Nations, established in 1948, to promote health and to control communicable diseases. It is based in Geneva, Switzerland. The United Nations relies on the WHO for providing international leadership on global health matters. This organization also helps shape the research agenda for health issues and sets standards for pollutants and other things that could pose a risk to health. WHO also regularly reviews data to set policies for maintaining health and a healthy environment.

zoonosis (plural: zoonoses) Any disease that originates in nonhuman animals and is later contracted by people. Many zoonotic diseases also spread among a host of non-human species. For instance, the type of swine flu that sickened people throughout the world in 2009 also infected marine mammals, including sea otters.

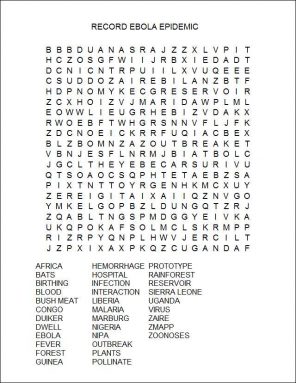

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)

(Click to enlarge for printing)