Restoring a sense of touch

An electric signal can trick a monkey’s brain into believing the animal’s finger has been touched

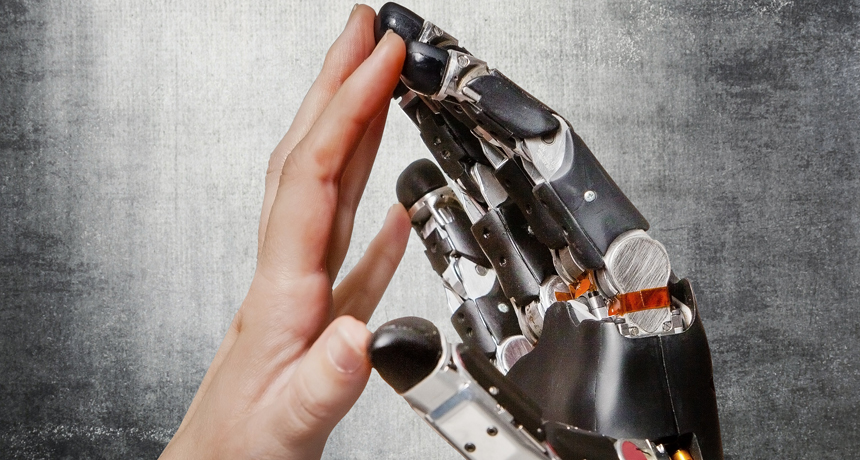

Electrodes implanted in the brain can send signals that make a monkey think its finger has been touched. The experiment suggests ways to build artificial hands or arms that restore a feeling of touch to users.

G. TABOT ET AL/PNAS 2013

Touch something, and your brain knows. The hand sends signals to the brain to announce contact was made. But that feeling of touch may not require making actual contact, tests in monkeys now show. Zapping brain cells can fool the animal into thinking its finger had touched something.

A person who has lost a limb or become paralyzed may need an artificial limb to complete everyday tasks. But such patients may not truly feel any objects they hold. The new findings point toward one day creating a sense of touch in those who use such artificial limbs. Psychologist Sliman Bensmaia of the University of Chicago worked on the new tests. His team’s findings appeared October 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The sense of touch is crucial to everyday tasks: People without it may have difficulty cracking an egg, lifting a cup or even turning a doorknob. That’s why restoring this sense is a major goal for designers of artificial limbs, Bensmaia told Science News.

In their new study, Bensmaia and his coworkers worked with rhesus monkeys. The scientists implanted electrodes — small devices that can detect or relay an electrical signal — into the animals’ brains. Then they trained the monkeys to look in a certain direction whenever a particular finger was touched. The electrodes took notes of the animals’ brain activity during that touch.

The scientists used the electrode data to identify which brain cells, called neurons, had become active.

Now the scientists used the implanted electrodes to zap those same neurons. And the monkeys reacted as though their finger had been touched. In fact, it hadn’t.

“We are trying to mimic natural signals in the brain,” Bensmaia explained toScience News.

The monkeys couldn’t use words to tell the scientists what they had felt. Instead, they communicated by looking in a particular direction — just as when they had really touched something.

Showing that the monkeys responded to the electrodes’ signaling was “really important,” Paul Marasco told Science News. He’s a neuroscientist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and did not take part in the monkey study. The new findings show how touch-sensitive devices could be built, he says. The new study also offers “a nice clear pathway” for figuring out how to restore a sense of touch to an amputee or someone with a spinal-cord injury. Spinal cord injuries can cause paralysis, sometimes eliminating the sense of touch to affected limbs.

The study shows how artificial limbs might be connected to the brain so that a person can “feel” with such a prosthesis. But such a super-sensory device doesn’t exist yet and scientists have a lot of work to do before people will benefit from one. Researchers must first figure out whether the electrodes would work in people the same way they do in monkeys. Bensmaia says such tests could happen soon.

“I think the foundation is laid for human trials,” he said.

POWER WORDS

amputee An individual who has lost all or part of some arm or leg due to injury or disease. The surgical removal of such tissue is referred to as an amputation.

electrode (in brain science) Sensors that can pick up electrical activity.

limb (in physiology) An arm or leg. (in botany) A large structural part of a tree that branches out from the trunk.

neuroscience Science that deals with the structure or function of the brain and other parts of the nervous system. Researchers who work in this field are called neuroscientists.

neuron or nerve cell Any of the impulse-conducting cells that make up the brain, spinal column and nervous system. These specialized cells transmit information to other neurons in the form of electrical signals.

prosthesis An artificial device that replaces a missing body part. A prosthetic limb, for example, replaces parts of or an entire arm or leg. These replacement parts usually substitute for tissues missing due to injury, disease or birth defects.

prosthetic Adjective that refers to a prosthesis.

psychology The study of the human mind, especially in relation to actions and behavior.

rhesus monkey (also called rhesus macaque)A small brown macaque with red skin on its face and rump, native to southern Asia. It is often kept in captivity and is widely used in medical research.