Return of the bed bug

Evolution and luck have been aiding this bloodsucking parasite’s global spread

Bed bug resting on the fur of one of its animal hosts — a bat.

Gilles San Martin /Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

By Brooke Borel

If you haven’t met a bed bug, count yourself lucky. These bloodsucking insects have been staging a dramatic comeback in recent years. They can be found in hotel rooms, airplanes, clothing stores and, occasionally, movie theaters. Accidentally bring one or more of these lentil-sized bugs home and your family could have trouble evicting them.

The wingless bugs are reddish-brown, oval-shaped and have six legs. Some people think bed bugs smell musty. Others compare their scent to rotting fruit or pencil shavings.

Bed bugs live on blood. They usually eat every few days or week, but they don’t need to eat that often to survive. The tiny bugs can go months without a meal. After such an unwanted fast, or even any time they haven’t recently fed, their bodies will be flat. And that helps them hide in little cracks near a bed. But once a bed bug has gorged on a meal — usually human blood, and usually while you are asleep — it plumps up like a miniature balloon. Then it returns to hiding in wait of its next meal.

But despite its modern infamy, this pest has been around for a long, long time — hundreds of thousands of years. The earliest bed bugs probably lived in caves, feeding on bats. Those caves may have been in the Middle East, but no one knows for sure. When early humans or their relatives started spending time in such caves, the bugs may have started biting them instead of the bats.

Today, some bed bugs still live with bats in caves, churches and attics in Eastern Europe, says Ondřej Balvín. As an entomologist, he studies insects. In 2012, Balvín and his colleagues at Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic, studied DNA from bed bugs. They compared DNA from the bugs that still feed on bats to the DNA of bed bugs that feed on people. This helped show how long ago bed bugs switched to dining on us.

How?

Scientists know how often DNA typically changes over time, or mutates. The scientists then applied that knowledge to the changes they saw in the DNA of bed bugs slurping human blood versus bat blood. These data suggested bed bugs began living with — and feeding on — our early relatives some 245,000 years ago. More research must be done to confirm that number. But if it’s right, it means the bed bug may predate modern humans.

Out of the caves

However long ago that was, the pest followed our ancestors as they moved out of caves. Bed bugs also are good at hitchhiking. Today, for example, they can hide away in suitcases or bags to move from one home to another. Back in the caves, the same thing likely happened. Only then, the bugs probably latched onto our ancestor’s furs or whatever else they wore or carried.

The parasites were a common pest in the United States and elsewhere until the late 1940s. That is not long after people started using a powerful new insect killer: DDT.

This bug killer could rid people of all sorts of unwanted pests, including flies and mosquitoes. Americans and people elsewhere sprayed DDT all over their homes. There was even wallpaper that had DDT inside it. The poison probably didn’t wipe out all of the bed bugs. But it did kill enough of them to make the bugs rare.

Until, that is, they found a way to bounce back.

The big comeback

Today, exterminators in all 50 U.S. states are treating bed bug infestations. Spotting new outbreaks also has been increasing rapidly. In the early 2000s, one survey found that only 25 percent of exterminators had been called out to treat bed bugs. By 2011, 99 percent had done so. A similar trend has played out across the globe. One study, for instance, found that by 2006, Australians were battling 46 times as many bed bug infestations as they had just six years earlier.

How did bed bugs become so common after almost disappearing? Experts think there may be many reasons working together.

“I really do think it was arrogance on our part to think that we had stopped a biological system,” says Dini Miller. “Really, I’m kind of surprised we didn’t have this resurgence earlier.” Miller is a bed bug expert at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Best known as Virginia Tech, its located in Blacksburg.

One big part of the bed bug picture is the ability of these pests to adapt to their environment. This is known as evolution.

An organism’s genes are always developing random changes, called mutations. If one of those chance mutations makes a bed bug better able to survive DDT, that bug will live. When it reproduces, its offspring also may carry this now-beneficial gene.

Over time, DDT killed off the sensitive bugs. This left behind more and more of the bugs with that new genetic tolerance to the poison. Eventually, DDT had little or no effect on most bed bugs in heavily treated communities.

Americans stopped using DDT in the 1970s. That’s when evidence began to show the chemical was hurting birds and other valued wildlife. But in some other countries, DDT is still allowed for some uses (such as fighting the mosquitoes that carry malaria). Scientists think that pockets of DDT-resistant bed bugs survived in these countries even when the bugs no longer were common in the United States.

Bed bugs: The ultimate carry-ons

There’s another reason bed bugs have been emerging as a growing problem. They’ve been on the move. Big time.

Starting in the 1980s, people started traveling by airplane more often because new rules made it cheaper and easier to fly. As the price of tickets dropped, more people could afford to travel long distances. It also became easier to fly even between very remote countries.

Experts now think that as people throughout the world started moving more, they began carrying DDT-resistant bed bugs with them. No one is sure exactly where, however, those resistant bugs came from.

Warren Booth is an entomologist at the University of Tulsa in Oklahoma. He is among researchers who think the bugs likely came from one region of the world (although they don’t yet know where). Other scientists aren’t so sure. For instance, Michael Potter of the University of Kentucky in Lexington, thinks resistant bugs may have migrated from many regions at once.

Another advantage for the bugs: More people live in cities than ever before. Because city dwellers tend to live close together — such as in apartment buildings — bed bugs don’t have to move far to find new hosts.

Other features of modern life also may have played a role in the bed bugs’ spread. People who travel spend time in a lot of environments that are friendly to bed bugs. In minutes, a planeload of people from one city will unload and a new group will take their seats. Hours after one hotel guest checks out, a new guest may check into the same room. And then there are all of those people who buy used furniture or rescue it from some discard pile on the street.

Through all of these ways, people have been making it easier for the bed bugs to find new hosts on which to dine.

As these pests have spread, they’ve also proven harder to kill. One big reason is that few insecticides that are effective at killing bed bugs also are considered safe enough to use in our bedrooms.

Pyrethroids (Py-REETH-roids) are one class of chemicals that can be used there. Unfortunately, they kill bed bugs in a way very similar to how DDT works. So all of the bed bugs that can stand up to DDT also tend to be immune to the effects of pyrethroids.

Like Potter, Subba Palli is an entomologist at the University of Kentucky. In 2012, he and a team of scientists found that some bed bugs also have special versions of molecules called enzymes that help them break down insecticides. That tends to make the chemicals less deadly. His team reported its findings in PLOS ONE.

The next year, in 2013, researchers at Virginia Tech found evidence that some bed bugs may be evolving thicker shells, known as exoskeletons. This could make it harder for the poisons to get in and do their damage. Dini Miller, Reina Koganemaru and their team reported the finding in Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology.

“It’s pretty fascinating to think about how these have all evolved,” says Booth at Tulsa. While it’s proven good for the bugs, “it’s not good for those that have infestations in their homes.”

Fighting back

Since entomologists figured out how to raise bed bugs in the lab, they have begun learning all kinds of information about the insects’ behavior. They also are probing new ways to control the bugs. That’s the good news. The not-so-good news: It will take a lot more work before that research turns up new and improved bed-bug killers that are ready for prime time.

For example, scientists have long known that bed bugs, like many insects, talk to each other through chemicals called pheromones. One type — aggregation pheromones — help bed bugs find their way back to their hiding places after they bite you. These chemicals show up in bed bug poop. These signaling chemicals attach to sensors in the bed bugs’ antennae. As the insects get closer to their hiding place, the pheromones get stronger and stronger.

The researchers looked at a bed bug pedicel under a powerful microscope and found it had tiny smooth structures with little holes. These may be olfactory organs, the bed-bug equivalent of our nose.

In the lab, researchers have identified some of the chemicals that make up the pheromones that bed bugs find so alluring. They are now trying to develop traps that use these pheromones to coax the pests to their death. Gerhard Gries heads one team in Canada working on this at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia. Last December, his team published a paper in Angewandte Chemie describing six of the chemicals that make up the aggregation pheromones. Five of the chemicals attract the bugs to their hideouts. The sixth makes the bugs want to stay there (at least until they get hungry again). A bed-bug trap employing these baits might cost only pennies, the scientists say.

Still, such bug traps won’t clear an infestation — unless the pests actually climb into them. And not all bugs will enter a trap, even one perfumed with pheromones. Some bugs might instead prefer the smell of their original homes. Because of this, scientists also are probing new ways to kill bed bugs without using pyrethroids and other commercial chemicals.

Today, it costs up to $256 million to create each new pest-killing chemical, according to CropLife America. It’s a group that represents companies that make pesticides. It also takes almost 10 years of research testing to bring each new bug killer to market.

That’s why researchers at Pennsylvania State University in State College are excited about a fungus called Beauveria bassiana (Bo-VAIR-ee-ah BASS-ee-AH-nuh). It occurs naturally in soils all over the world. It also kills insects. The fungus’ dusty white reproductive cells, called spores, stick to the outside of an insect. As the spores grow, they enter the insect’s body. Eventually, the spores bloom and clog the bug’s internal organs, killing it.

But even with all this exciting new research, the pest isn’t likely to disappear entirely, notes Stephen Doggett. He’s a medical entomologist at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, Australia. It takes a long time for scientific research to get tested and retested. Only after that can it be turned into a product that you can buy in the store. Another problem: Bed bugs are really hard to kill with any single method. Use just one and a species is likely to develop mutations that make it immune. That’s why exterminators usually have to use many different approaches at once.

Concludes Doggett: “Unfortunately bed bugs are going to be around with us for a long time, as no magical control solutions are on the near horizon.”

Brooke Borel is the author of Infested, a new book on bed bugs.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

antenna (plural: antennae) A pair of long and then sensory organs located on the head of arthropods, including bed bugs and other insects.

bed bug A parasitic insect that feeds exclusively on blood. The common bed bug, Cimex lectularius, sucks human blood and is mainly active at night. The insect’s bite can cause skin rashes and welts that sometimes look like a mosquito bite, but different people react in different ways.

bloom (in microbiology) The rapid and largely uncontrolled growth of a species, such as algae in waterways enriched with nutrients.

DDT (short for dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) This toxic chemical was for a time widely used as an insect-killing agent. It proved so effective that Swiss chemist Paul Müller received the 1948 Nobel Prize (for physiology or medicine) just eight years after establishing the chemical’s incredible effectiveness in killing bugs. But many developed countries, including the United States, eventually banned its use for its poisoning of non-targeted wildlife, such as birds.

DNA (short for deoxyribonucleic acid) A long, double-stranded and spiral-shaped molecule inside most living cells that carries genetic instructions. In all living things, from plants and animals to microbes, these instructions tell cells which molecules to make.

entomology The scientific study of insects. One who does this is an entomologist.

enzymes Molecules made by living things to speed up chemical reactions.

evolution A process by which species undergo changes over time, usually through genetic variation and natural selection. These changes usually result in a new type of organism better suited for its environment than the earlier type. The newer type is not necessarily more “advanced,” just better adapted to the conditions in which it developed.

exoskeleton An external system that supports the bodies of certain animals, including insects, crustaceans, and mollusks. In insects, the exoskeleton is made of a hard material called chitin.

gene (adj. genetic)A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

genome The complete set of genes or genetic material in a cell or an organism. The study of this genetic inheritance housed within cells is known as genomics.

infest To create a parasitic community, such as when wasps infest the porch of an abandoned house. Such a community of pests is known as an infestation.

insect A type of arthropod that as an adult will have six segmented legs and three body parts: a head, thorax and abdomen. There are hundreds of thousands of insects, which include bees, beetles, flies and moths.

insecticide A poison applied to kill insects.

olfaction (adj. olfactory) The sense of smell.

organ (in biology) Various parts of an organism that perform one or more particular functions. For instance, an ovary is an organ that makes eggs, the brain is an organ that interprets nerve signals and a plant’s roots are organs that take in nutrients and moisture.

pedicel A slender stalk or stalk-like part. It normally occurs at the base of something, such as a flower, where it will be attaching to the stem.

pheromone A molecule or specific mix of molecules that makes other members of the same species change their behavior or development.Pheromones drift through the air and send messages to other animals, saying such things as “danger” or “I’m looking for a mate.”

pyrethroids A modern family of chemicals that are used to kill insects. It is a human-made version of a naturally insecticide that is made from crush chrysanthemum flowers.

species A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.

spore A tiny, typically single-celled body that is formed by certain bacteria in response to bad conditions. Or it can be the single-celled reproductive stage of a fungus (functioning much like a seed) that is released and spread by wind or water. Most are protected against drying out or heat and can remain viable for long periods, until conditions are right for their growth.

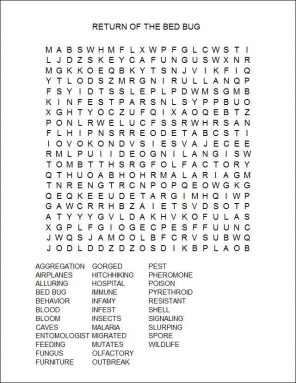

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)