Roboroach and company

Cockroaches and lobsters inspire robots that navigate in darkness and track smells.

By Sarah Webb

When you see a cockroach scurry across the floor or a lobster crawl over sand in an aquarium tank, you probably don’t think of robots.

|

|

A cockroach.

|

| CDC, Public Health Information Library |

Robots are machines. People build and program them to assemble cars, vacuum floors, or do other tasks. Some venture into dangerous places, such as volcanoes and minefields, where people can’t go safely. Others guard warehouses or simply serve as pets.

Many robots have sensors to detect what’s happening around them. They process this information and react to what they detect.

Scientists and engineers have observed that animals can move and respond in ways that people can’t. Dogs, for example, can hear high-pitched sounds that people can’t hear and smell odors no human nose can detect. Octopuses use a form of jet propulsion to get around and can cram themselves into tiny spaces (see “Walktopus”).

So, it makes sense for researchers interested in robots to learn more about how animals interact with the world around them (see “A Sense of Danger”). Using animals, such as cockroaches and lobsters, as models, they can then try to create robots to do even more things that people can’t do.

Roach navigation

Why would you study a bug to build a robot?

Cockroaches are really good movers, says Noah Cowan. He’s a professor of mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Roaches run amazingly quickly for their size. They can dash about in total darkness, creep into tiny crevices, and get around all kinds of obstacles (including the shoes and flyswatters of people trying to squish them).

Because they move so well in difficult conditions, cockroaches could teach engineers how to build robots that can navigate in tight and unlit spaces.

A cockroach has two long antennas with thousands of sensors along each one. Cowan and researchers in his lab focused on how a cockroach uses its antennas to steer.

To find out, they first blindfolded cockroaches and placed them in a dimly lit chamber. Then they used a camera to film exactly how the cockroaches used their antennas as they moved.

It turns out that a cockroach can tell how far it is from a wall by how much its antennas curve as they brush against the obstacle. The insect can then adjust its movements accordingly. It’s the same idea as using your hand as a guide when you walk down a dark hallway. But because your hand isn’t designed for sensing distance, you probably can’t move as fast as a cockroach.

|

|

Johns Hopkins student Owen Loh developed this cockroach-inspired robot antenna, which is equipped with six strain gauges to sense bending.

|

| Photo by Will Kirk, Johns Hopkins University |

To apply this idea, Cowan and his coworkers built a cockroach-like antenna for a small robot with wheels. Their antenna is made of flexible plastic, which allows it to bend as the robot moves and touches its surroundings.

The antenna is also equipped with several strain gauges. Strain gauges measure how much an object bends. Measurements go from the strain gauges to a computer. A computer program then translates the bending data into distance information that the robot can use to tell how far it is from a wall.

|

|

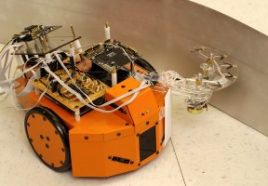

This wheeled robot uses a special, cockroach-inspired antenna to sense walls and other obstacles.

|

| Photo by Will Kirk, Johns Hopkins University |

Although it has far fewer antenna sensors and moves more slowly than a cockroach does, the robot steers itself along curves and around obstacles—just like a cockroach in the kitchen.

Cowan isn’t the only robotics researcher who has studied cockroaches to build better robots. Several teams, for example, have created six-legged robots that imitate the way a roach moves it legs, scampers over rough terrain, or evades obstacles. One group has built a roach-inspired machine that climbs walls. Another group has even designed a little mobile robot that’s driven by a live cockroach.

Underwater smells

Like cockroaches, American lobsters have antenna structures that they use to sense the world around them. They also have a second pair of projections on their heads, usually shorter and stubbier than antennas, called antennules.

Using these antennules, lobsters have a particularly good sense of smell, says Frank Grasso. He’s a psychology professor at Brooklyn College.

A lobster’s sense of smell is based on tracking chemicals in the water, and it uses this ability to find food such as clams.

|

|

An American lobster, Homarus americanus, has large claws.

|

| OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP) |

Grasso and his team have spent a great deal of time learning how lobsters trace the odor of food to its source. This information has helped them design, build, and program robots that track the amount of various chemicals in water to their source in the same way that a lobster does.

One resulting robot, named Wilbur, doesn’t look much like a lobster. But it’s mobile and has sensors that respond to the presence of certain chemicals.

|

|

Inspired by a lobster’s sense of smell, Wilbur is a chemical-sensing robot.

|

| Courtesy of Frank Grasso |

The researchers have tested their “robolobsters” under realistic conditions in the Red Sea. Although they probably weren’t analyzing and responding to smells in exactly the same way that lobsters do, the robots still managed to work as well in the ocean as they do under controlled conditions in the lab.

Such robots may eventually be used to track and pinpoint underwater sources of pollution, detect and locate unexploded mines and bombs, and look for deep-sea vents and other ocean features.

A firm grasp

Another good model for a robot might be the slipper lobster.

Slipper lobsters are covered with large plates and don’t have claws. They’re also not as fast as their American lobster and spiny lobster cousins. “These guys are like Eeyore—slow-moving and lethargic,” Grasso says. “They can go months without eating a clam.”

|

|

A slipper lobster in captivity.

|

| Courtesy of Frank Grasso |

But when they’re hungry, slipper lobsters walk up to a clam and poke it with their sharp, pointed legs. Without looking, they pick up the clam, turn it to the right position, and put pressure on it to open the shell. Sometimes, they cut a small notch in the shell and pry it open with one of their legs.

Slipper lobsters are a good model for how people grasp and hold things, Grasso says.

In the same way that a person has 10 fingers, a slipper lobster has 10 fingerlike hinges (its legs and the plates). Because a slipper lobster handles clams from the underside of its body, it has to rely on its sense of touch. To do so, it needs to know the position of each leg at all times.

If he could build a robot that could open clams the way a slipper lobster does, he could apply the technology to many other problems, Grasso says.

One result could be an improved artificial hand or a robot that can grasp and manipulate objects with little direction from people.

Imitating nature

Cowan and Grasso are just two members of a large group of researchers who are studying animals to help design, build, and program robots with superhuman abilities. They’re learning a great deal about the animals themselves, and they’re creating ingenious machines that do amazing things.

Developing such robots could lead to the rescue machines of the future. Roboroach could use its antennas to feel its way around obstacles at a disaster scene; robolobster could smell smoke or detect a toxic chemical and follow it to its source. With such help, firefighters and other rescue personnel might be able to save lives without getting hurt themselves.

Going Deeper: