Robots and ‘green energy’ win the day at Intel ISEF

Top awards go for a window-washing robot, low-cost big batteries and ‘green’ capacitors

The top three award winners at the 2018 Intel ISEF competition are, from left: Meghana Bollimpalli, Oliver Nicholls and Dhruvik Parikh.

Chris Ayers/Society for Science & the Public

By Sid Perkins

PITTSBURGH, Pa. — Maybe it took nerves of steel. Or maybe these young researchers merely showed steely determination. But dozens conquered the odds, here in Steel City, to claim big prizes. Roughly 1,790 students competed, this week, for almost $5 million in prizes in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). And about 35 in every 100 of the finalists would go home with some award.

Oliver Nicholls took home the top prize and $75,000. This 19-year-old from Barker College in Sydney, Australia, designed and built a robot that can wash the windows on skyscrapers. His project earned him the Gordon E. Moore award, named for Intel’s co-founder. “I hadn’t expected to get this far,” he told Science News for Students. “I was hoping for a second place, maybe.”

Two other winners also took home huge Grand Awards as well.

ISEF has been honoring young researchers since 1950. Created and still run by Society for Science & the Public, this remains the world’s largest international pre-college science competition. Sponsored this year by Intel, ISEF brought together students from 81 countries, regions and territories. Their 1,383 projects competed in 22 different research categories.

“The breakthrough ideas presented by the winners and finalists demonstrate how the brilliant minds of future generations will make the world a better place,” says Maya Ajmera, president of the Society, based in Washington, D.C. “These young innovators are the stewards of our future, and we look forward to seeing all that they accomplish as they continue to pursue their interest in STEM.” (The term stands for science, technology, engineering and math.)

Spritz, scrub, squeegee, repeat

Washing windows on skyscrapers is a dangerous job. That became clear to Oliver Nicholls when he learned of two local accidents. These inspired the teen to invent a picnic-cooler–sized robot to take on the risks instead.

A computer controls Oliver’s 12-to-15 kilogram (26-to-33 pound) device. It sprays a little water onto a window, then rubs microfiber-covered scrubbers across the glass to scrub away dirt. A windshield-washer–style squeegee removes any excess water.

When the robot needs to move from one window to another, propellers kick into gear. They push the robot away from the building. Cables then pull the robot to the next window. At this point, a different set of propellers holds the robot tight against the window as the cleaning cycle repeats.

If commercial, this robot might be able to pay for itself after cleaning just one 7-story building, Oliver estimates.

Besides winning the overall competition, Oliver’s project also led the pack in the Robotics and Intelligent Machines category.

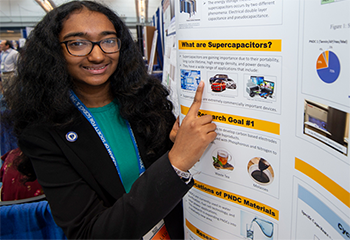

Cooking up low-cost supercapacitors

Capacitors (Kah-PASS-ih-torz) are devices that store energy. Unlike batteries, which store energy chemically, capacitors do so by physically storing electric charge — electrons (the negatively-charged particles in atoms). Supercapacitors, of course, are capacitors that can store a relatively huge charge.

For some applications, supercapacitors outperform batteries. Why? When energy is needed, they can deliver a lot of it fast. One example where this is prized: a medical device called a defibrillator (Dee-FIB-rih-lay-tor). It’s used to zap a person’s chest when they’re having a heart attack, says 17-year-old Meghana Bollimpalli. She’s an 11th-grader in Arkansas at Little Rock Central High School. Other uses for supercapacitors include military equipment.

One big problem, though, is the high cost of most supercapacitors. They tend to use costly elements, such as platinum. Some devices may run $4,000. Even the cheapest supercapacitors can cost about $300. Meghana thought there must be a way to cut their cost.

And at Intel ISEF she reported finding one.

The teen wanted a carbon-rich material that could store lots of electrons. She also wanted the ingredients to be low-cost and easy to obtain. To find them, she essentially went to the pantry.

She started out with molasses, used tea leaves and tannin. That last material is a bitter, carbon-rich substance produced by some plants (including tea). To this mixture, she added a pinch or two of ingredients that contained nitrogen and phosphorous, which are common plant nutrients. Those elements would help the other materials store electrons, she points out.

Meghana then cooked the mix in a microwave for 30 minutes. The end result was a carbon powder. She could use it to coat an electrode in the supercapacitor, she says. (Electrodes are the parts of a capacitor or a battery where electrons are supplied to a circuit or received from that circuit.) If her new powder were packed tightly enough, it could even become the electrode.

Meghana’s material can store about 90 percent as big of a charge as an equivalent mass of some supercapacitors for sale today. But cost is where her version shines. Instead of costing hundreds of dollars, one made with her recipe would likely cost less than $1, she estimates.

This project was not only deemed best in the Chemistry category, but also earned Meghana an Intel Foundation Young Scientist Award and $50,000.

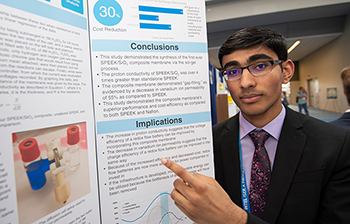

Building a better battery

Batteries don’t last forever. They’ll run down as they are used. But batteries also can run down when not in use. That happens whenever electrons or other charged particles leak from one side of a battery to the other, notes Dhruvik Parikh, 18. The senior attends Henry M. Jackson High School in Bothell, Wash.

In a battery, electrons flow from the negative electrode, known as an anode (AN-oad), through to the positive electrode, or cathode (KATH-oad). But a battery’s charge can sometimes drain down when the barrier between the positive and negative electrodes is leaky, Dhruvik explains. This can be an especially big problem for the large batteries used to store power generated by wind turbines and solar panels. Those big batteries often have liquids inside them as well (not the pasty materials typically found inside small portable batteries). With those liquids, leakage of charged particles between the two sides of the battery is even easier.

To limit that, Dhruvik looked to create a better barrier to separate the two chambers of liquids inside big batteries.

He started out with a plastic membrane 0.15-to-0.5 millimeters (0.006-to-0.02 inch) thick. Full of microscopic holes, that plastic was fairly leaky. So the teen coated it with a paste. It included a silicon-rich material called tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEH-tra-ETH-ul Or-tho-SIL-ih-kayt). When this chemical reacts with water, it makes silica. (That’s another name for silicon dioxide, the material in sand.) And that silica did a pretty good job of plugging up the tiny holes in the plastic membrane, Dhruvik found.

This novel membrane cut the leak of charged particles inside batteries by more than half, Dhruvik showed. His new material also is about 30 percent less costly than the material now used inside big liquid-filled batteries. That’s a big deal, he notes. Today, that barrier can account for up to 40 percent of a big battery’s total cost.

Dhruvik’s project beat all the others in the “Energy: Chemical” category. Like Meghana, he, too, picked up an Intel Foundation Young Scientist Award and $50,000.

Seven of these “best of category” winners also earned trips overseas. Some will visit research labs in India. Others will visit science fairs or attend youth science forums in Europe. Some of the roughly 625 winners at this year’s competition even won college scholarships.

“Intel congratulates Oliver Nicholls, Meghana Bollimpalli, Dhruvik Parikh and all of the participants on their groundbreaking research,” notes Rosalind Hudnell. She is an Intel vice president and president of the Intel Foundation. “When students from different backgrounds, perspectives and geographies come together and share their ideas,” she says, “there is no limit to what they can achieve.”

Other major Intel ISEF 2018 award winners

The following students each won “best of category” awards worth $5,000 in this year’s competition:

Animal Sciences: Anna Spektor, 17, and Ayman Isahaku, 18, of Nicolet High School in Glendale, Wisc.

Behavioral and Social Sciences: Amy Shteyman, 18, of John L. Miller Great Neck North High School in Great Neck, N.Y.

Biochemistry: Rhea Malhotra, 15, of Moravian Academy in Bethlehem, Pa.

Biomedical and Health Sciences: Nabeel Quryshi, 18, of University School of Milwaukee in Milwaukee, Wisc.

Biomedical Engineering: Ronak Roy, 16, of Canyon Crest Academy in San Diego, Calif.

Cellular and Molecular Biology: Ella Feiner, 18, of Horace Mann School in Bronx, N.Y.

Computational Biology and Bioinformatics: Marissa Sumathipala, 17, of Broad Run High School in Ashburn, Va.

Earth and Environmental Sciences: Vasily Tremsin, 18, of Campolindo High School in Moraga, Calif.

Embedded Systems: Burzin Balsara, 18, and Malav Shah, 18, of Plano Senior High School in Plano, Texas.

Energy: Physical: Sathya Edamadaka, 16, of High Technology High School in Lincroft, N.J.

Engineering Mechanics: Frederik Dunschen, 19, of Friedensschule Munster in Munster, Germany.

Environmental Engineering: Raina Jain, 15, of Greenwich High School in Greenwich, Conn.

Materials Science: Daniel Kang, 16, of John F. Kennedy High School in Tamuning, Guam.

Mathematics: Muhammad Abdulla, 18, of West Shore Junior/Senior High School in Melbourne, Fla.

Microbiology: Logan Dunkenberger, 17, of Roanoke Valley Governor’s School for Science and Technology in Roanoke, Va.

Physics and Astronomy: Ana Humphrey, 17, of T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria, Va.

Plant Sciences: Yueyang Fan, 16, of No. 2 High School of East China Normal University in Shanghai, China.

Systems Software: Ruihua Chou, 16, of The High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China in Beijing, China.

Translational Medical Science: Edwin Bodoni, 17, of Cherry Creek High School in Greenwood Village, Colo.