Satellites find big climate threats — ultra-emitters of methane

Most are in big oil- and gas-producing countries, such as Russia and the United States

Oil companies often deliberately vent, or release, natural gas to the atmosphere. Many times they flare — or burn — the gas (as shown here). Even flaring may not burn all the gas, which means that this, too, can be a big source of methane entering the atmosphere.

Rex_Wholster/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Methane gas is 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at trapping sunlight and warming the atmosphere. And large amounts of this methane are leaking into the air all the time. Some of the worst leaks come from sites where drilling for oil and gas takes place. Other big leakers can be the pipelines that move these fossil fuels. But it’s been hard to find the worst methane leaks. Now, scientists are using satellites’ eyes in the sky to find them.

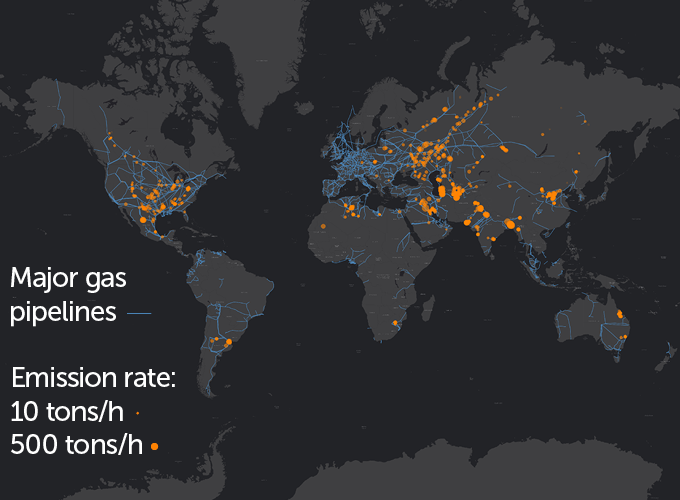

A super-big leaker — or “ultra-emitter” — can spew at least 25 metric tons (27.5 U.S. tons) of methane into the air each hour. Some release 500 metric tons (550 U.S. tons) per hour.

Stopping all of these big leaks would be as good for the planet as pulling 20 million vehicles off the roads for a year. Such a move also could save billions of dollars, says Thomas Lauvaux, who led the new study. He’s a climate scientist at the University of Paris-Saclay, France. His team shared its findings February 4 in Science.

Finding big methane leaks has been a challenge as the gas comes from so many places. Natural seeps release some. Cow burps do too. But much had seemed to come from human-made sources, such as oil and gas pipelines. Massive methane bursts during oil and gas production can be due to accidents or leaks, Lauvaux says. Sometimes, though, they’re on purpose. Clearing gas from a pipeline for maintenance might require shutting it down for days. So managers often take an easier, but more wasteful approach. They open both ends of the pipeline and try to burn off the gas by “flaring.” But a lot of the gas can still escape.

Planes had helped pinpoint some large sources. But they can survey only small areas and for a short time. Lauvaux and his team realized that satellites could scan far larger areas for months or years. So this group turned to satellite images from 2019 and 2020. Most of the 1,800 biggest methane sources in these images were in just six countries. Turkmenistan topped the list. Russia was in second place, followed by the United States, Iran, Kazakhstan and Algeria.

Cleaning up the biggest leakers would go a long way in cutting global methane emissions, says Euan Nisbet. He’s a geochemist in England at Royal Holloway, University of London. It’s like “if you see somebody badly injured, you bandage up the bits that are bleeding hardest,” he explains.

The new study relied on images from an instrument called TROPOMI (short for Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument). It’s being carried by a European Space Agency (ESA) satellite. Some of those images show flaring along a pipeline track as two giant plumes, Lauvaux says.

Hot spots

This map shows the world’s ultra-emitters of methane (orange circles). The biggest ones (larger orange circles) release up to 500 metric tons of the gas per hour. Blue lines show gas pipelines. Some ultra-emitter sites follow the routes of those pipelines, such as in Russia.

Where methane ultra-emitters were detected in 2019–2020

TROPOMI doesn’t see well through clouds. So some regions, such as Canada and the tropics, weren’t included in the new analysis. That doesn’t mean those regions aren’t spewing methane, Lauvaux says. He and other scientists are now trying to plug the data gaps by using other satellites that can see through clouds better.

More than 100 countries signed a Global Methane Pledge at a November 2021 United Nations’ summit on the climate. These countries promised by 2030 to cut their methane releases by 30 percent. A better global map of methane ultra-emitters could help countries target the biggest problem areas first.

Importantly, the new study “encourages action rather than despair,” says Daniel Jacob. He’s an atmospheric chemist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.