Science works to demystify hair and help it behave

Growing data can help us control our hair — even extra-curly — to keep it looking its best

Hair scientists have traditionally focused less on the special needs of naturally curly hair than on other types. That’s starting to change. And what they’re finding could benefit all of us.

Drazen/E+/Getty Images Plus

Michelle Gaines’ hair naturally curls into tight coils. Keeping it neat and healthy has proven a challenge for this busy polymer chemist. She’s read all those product promises and watched online videos about how to tame it. Her friends’ well-meaning advice didn’t help much either.

“It’s literally been trial and error,” says Gaines, who works at Spelman College in Atlanta, Ga.

In frustration, she turned to her science.

Human hair can vary widely in texture, shape and curl patterns. These differences affect its strength and more. So, too, do our hair-care practices and treatments. Gaines is among a growing number of scientists working to better understand these strands of fibrous protein that sprout from our heads.

Some researchers are focusing on what the differences in curly hair mean for its strength and other traits. Others are probing how varying hair and scalp conditions affect our locks. Still others are studying hair-care practices and hair-care products, including shampoos and conditioners.

Some of their findings could help you take better care of your hair — or point to personal do’s and don’ts. After all, no matter what type you’re born with, you want it to be healthy. And we all want our hair to look awesome.

Straight? Curly? What type do you have?

Everyone’s hair has the same basic chemical composition. Yet from one person to the next, those strands popping out of our scalps vary greatly. One of the most obvious ways is in their curliness. But they can also naturally differ in thickness, color pigments, strength, texture and more.

Hair is mostly made up of proteins, such as keratin. It also has small amounts of lipids (fatty substances) and sugars. Scientists have shown that the types of proteins in straight hair can vary a bit from those in curly hair. But what we know about those differences doesn’t yet provide a good way to classify hair, says Gabriela Daniels. She’s part of a hair-research team at the London College of Fashion in England. It’s part of the University of the Arts London.

Daniels and others wrote about that and other hair qualities in the February 2023 issue of the International Journal of Cosmetic Science.

Some studies have tried to organize hair types based on broad racial groups. But people in any one group don’t all have similar hair. For example, the hair of people whose ancestors came from Europe can range from very straight to wavy or tightly coiled. It can be thin or thick, oily or dry, brittle or bouncy. And it can naturally vary as much in color as it does in texture and strength.

Plus, many people’s ancestors come from multiple places. So, the genes that tell our hair how to grow can differ a lot — even within a family.

Some traits do show up more often in groups whose ancestors came from some particular part of the world. Still, even the hair of individuals whose ancestors came from the same place can differ broadly. And there’s a lot of overlap among groups from different places on a range of traits. That includes how — and how much — their hair strands curl.

Until recently, Sandra Koch worked at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. While there, she was part of a team that studies characteristics of human hair. In the American Journal of Biological Anthropology this past July, they showed how measurements of different traits vary across — and within — groups whose ancestors come from different parts of the world.

Based on those data, they now argue for getting rid of outdated racial categories for hair. Assigning generic ethnic labels can prove misleading, Koch says, because hair “really is variable.”

Koch now works as a forensic scientist for the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Md. Ideally, she says, people in forensics share as much information about trace evidence as possible. Features of hair samples, for instance, might be more common among groups whose ancestors come from some geographic region. But detectives also need to realize how widely any group’s hair varies.

Doing so may keep them from improperly eliminating suspects based on findings about hair at a crime scene, she says. It may also strengthen the value of this evidence if a case goes to trial.

Under the microscope and in the stretchers

Teens aren’t likely to go to trial over their hair. But various features matter when it comes to how they care for it. That’s why the hair-care industry has been working on other ways to classify hair.

Back in 2007, scientists at L’Oréal in France divided hair into eight groups, based on its curliness. About a decade earlier, hair stylist Andre Walker defined hair groups based on curl, texture and other traits.

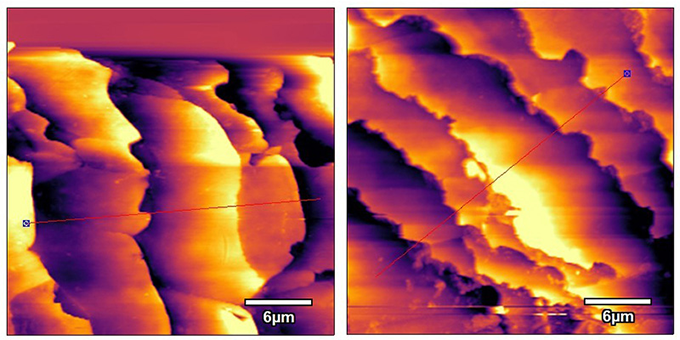

More recently, Gaines and her team have turned to scanning electron microscopes and other tools to classify hair.

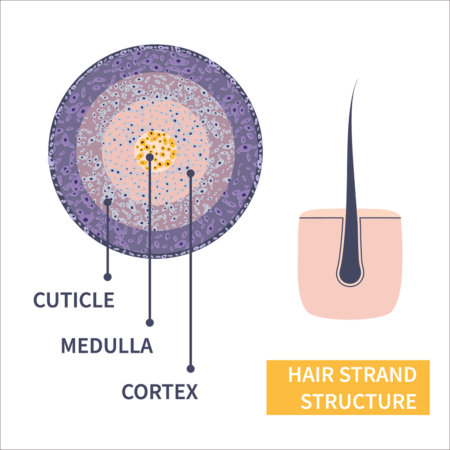

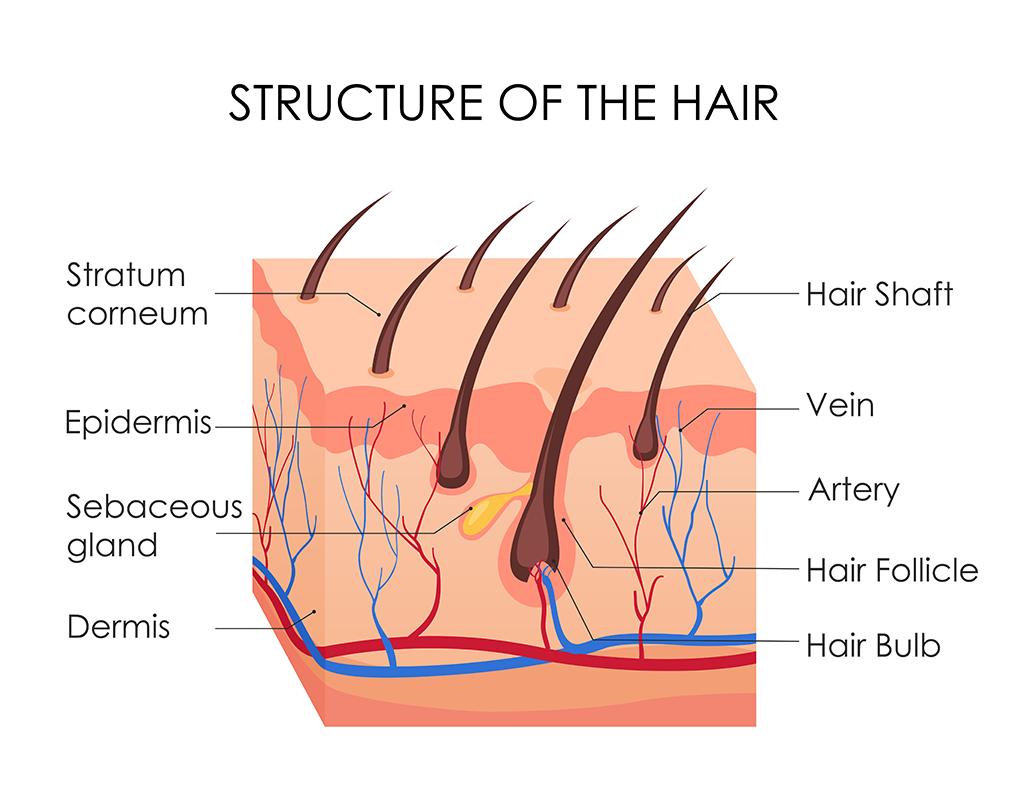

This shows the general structure of a cross-section of a strand of hair. That cross-section in tightly coiled hair tends to be more elliptical than circular. A hair shaft grows from a structure in the skin called a hair follicle (shown at right).

The outer layer, called the cuticle (KEW-tih-kul), has overlapping bits known as shingles. On straight or wavy hair, these usually lay flat and smooth, Gaines says. The next layer — the cortex — makes up most of a hair shaft’s volume. The thin, innermost layer is the medulla (Me-DUH-luh). It’s most notable in thick or coarse hair. Fine blonde hairs may have no medulla at all.

Gaines’ group then went on to suggest using additional geometric measurements to classify very curly hair. Among other things, the team measured the length of the contour waves that make up each hair strand’s curls. How far apart do the waves on them crest? And how many contour waves fit along each 3-centimeter (1.2-inch) span of hair?

Previous work had generally relied on simply eyeballing categories to rate hair’s curliness. The extremely fine details that Gaines’ group has collected now establish very precisely how tightly someone’s hair naturally curls.

Such measurements might one day help companies develop hair-care products that work better for specific hair types, Gaines says. Then, once you know which type yours is, you could pick shampoos and conditioners made to work best for your tresses.

Her team shared its new approach to classifying curly hair last year in Accounts of Chemical Research and at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

Fragile strands

Among other features, Gaines’ group measured hair’s tensile strength. That’s how much load it can support before it breaks. Curlier hair will stretch out more as pulling straightens it, her team showed. Breakage can then swiftly follow. This confirmed what earlier studies had found.

Bending hair also stresses it, notes Daniels at the London College of Fashion. Twisting — what scientists call a torsional force — also takes its toll. So, the full length of very curly hair may not bear a load as well as some small segment of it.

Strands of curly hair also tend to intertwine — or tangle — more easily than other types. And the more tangles, the greater the risk that hair will break. Friction, too, is hard on some hair types, Daniels points out. Even a pillowcase can cause friction at night, she says. In hopes of reducing that, some people with tightly curled locks will sleep on silk or satin pillowcases. Or, they may don sleep bonnets before bed.

Moisture is another issue. Everyone’s scalp exudes a natural oil, called sebum. Small amounts on hair help it hold in moisture. But this protective oil may not reach the ends of long or tightly coiled hair, Daniels notes.

Differences in thickness also may affect how fragile very curly hair is, says Catarina Fernandes. She’s a chemical engineer at the University of Coimbra in Portugal. Cross-sections of curly hair are more likely to look like ovals than circles. People of African ancestry with very curly hair also tend to have more variation than other groups in the diameter of a hair’s shaft along its length, she noted. So, it may have more points of weakness.

Hair is also more fragile when it’s wet or exposed to excess heat, such as curling irons or hair dryers. Researchers in South Africa showed this with samples from one curly-haired woman in her 30s. The data show how changing conditions can affect someone’s hair. At the same time, data from just one person mean the team can’t say its findings apply to all.

What are your hair cleansers doing?

Hair-care products aren’t yet tailored as finely as Gaines would like. But companies do offer products for general hair types, such as fine hair or coarse hair. Whatever traits your hair has, try to pick products designed for your tresses, Daniels suggests.

Everyone wants their shampoo to remove dirt and sweat. But those products also take out naturally protective oils. So, many products include moisturizers. Super-curly hair tends to be especially prone to dryness and frizz, though.

For people with very curly locks, Gaines’ team saw their hair-shaft shingles were packed so tightly together that they wouldn’t lie flat. That lets moisture escape. Moisture leaves when shingles on hair cuticles don’t evenly overlap each other, Gaines points out. Moisturizing products can help with that.

Another thing everyone should consider is a shampoo’s pH. A pH of 7 is neutral. Anything higher is alkaline. And a hair shaft? With a pH of about 3.7, it’s fairly acidic. The scalp is less so, with a pH of around 5.5.

So why would a shampoo’s pH matter? Alkaline can increase negative electrical charges on the hair surface. That increases friction and static electricity. And it can lead to cuticle damage and breakage. So concluded a team of Brazilian researchers in 2014.

Washing with hot water can also open the hair’s cuticles. A slightly acidic pH allows cuticles to close up, notes Procter & Gamble, a maker of many hair-care products. The issue is more pressing for curly hair, whose cuticle might be generally open, allowing more moisture to escape. These people “might require a slightly acidic product to close it up,” the company suggests.

So how might you identify an acidic shampoo? Short of doing a chemistry experiment, you won’t. When the 2014 study was done, the team analyzed 123 international brands of shampoos. Fewer than four in 10 had a pH lower than 5.5.

The study’s authors called for more work to find out what pH level might be best for scalp and hair health. They also suggested listing the pH on product labels. Many companies still don’t do this. But “there is a way to find out if a shampoo is low pH or not,” according to Shehnaz Shirazi. She’s the editor of Salon-Worthy Hair in London, England. Because that info is not on the label, you have to track down each product’s MSDS (short for material safety data sheet).

“We’ve researched over 470 shampoos and hair products, gathered their MSDS, asked manufacturers for details directly, and tested some with an electronic pH meter,” says Shirazi. From this, “we found only 28 low-pH shampoos.” She filtered out those using “the least chemicals and better reviews” and posted them to her blog on Nov. 6, 2023.

In the journal Polymers last year, Fernandes’ team at Coimbra reported data on three ways conditioners might help with pH issues. Some of them adjust hair’s negative electric charge. That can somewhat counter effects of alkaline shampoos. Conditioners also can coat hair strands with a film, which smooths the surface. That can restore shine and make hair feel softer.

Still other conditioners aim to strengthen hair with tiny bits of protein. Remember, Fernandes notes, hair is mainly made of proteins. “So, if it gets highly porous due to damage, we can use small proteins to penetrate the hair fibers and get some of these lost proteins restored.”

Think of it as adding extra bits of blocks back to a wobbly Jenga® tower. Filling in some weak spots makes the hair stronger. But “this is just a physical interaction,” she adds. The next time you wash your hair, shampoo will remove some or all of those bits of protein. So, ongoing conditioning is needed, her team notes.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Caring for your locks

Hair-care research should factor in how people feel about their hair, as well as how they take care of it, says Daniels. She and Maxi Heitmeyer recently shared ideas about this in the International Journal of Cosmetic Science. Heitmeyer, a social psychologist, also works at the University of the Arts, London.

For one July 2024 paper, their team talked with 14 curly-haired people about their hair-care routines. They also asked how these people wanted their hair to look and feel. The team used the answers to build a category system that focused on different goals for managing hair. The system worked especially well for people with curly hair, the team reported this October.

The pair chose to focus on curly hair because that group has often been overlooked in other studies. Their new findings might help hair-care-product labs set up test conditions that better reflect how people take care of their hair, Daniels says. It also can help stylists better match products to their clients’ needs. The findings might even help consumers begin to focus better on specific goals for their hair and how they want to care for it.

For instance, some people have to share bathrooms with lots of other people, getting little time there to themselves. For such people, a product that must be used on wet hair may prove a hassle.

Super-curly hair comes with challenges. But it can look great in a variety of styles. Choose a look, products and a practical routine that will be good for your hair so it stays strong and healthy.

And no matter what type of tresses you have, “how we feel about our hair makes a difference,” Daniels says. You don’t have to spend a whole lot of time or money. But learning the science of hair could pay off. And it’s good to think about what you want to get out of a hair-care routine that’s practical for you.

Indeed, “teens should be able to learn a bit more about their hair and look after it in a way that is easy and fun,” Daniels says. When our hair looks good, we’re more likely to feel good, too.