Science offers recipes for homemade coronavirus masks

With a snug fit, some might filter almost as well as medical gear, studies suggest

Many people wear homemade masks to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus. How well those masks work depends on what they’re made of, and how well they fit.

ti-ja/E+/Getty Images

More and more people are wearing homemade masks at supermarkets, hardware stores, workplaces and more. The goal is to slow the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19. Now two new studies provide data on which fabrics to use. Also important, they show: a snug fit.

To see why, it helps to understand how the virus travels through air. People infected with COVID-19 breathe out some of the virus particles in very small droplets of spit, snot or water vapor. Without something to stop them, the larger droplets will fall within a few feet. That’s one reason why physical distancing between people matters. But the tiniest droplets, called aerosols, can remain aloft for a few hours before falling onto surfaces. That’s also a reason for frequent handwashing, cleaning of surfaces and other sanitizing steps.

Masks can help to limit the spread of aerosols. But medical-grade masks are in short supply. Hospitals and health practices need them most. Among the public, therefore, many people have begun making masks at home. It’s been unclear, however, which materials might work best.

Aerosols can range from about 6 micrometers (or microns) down to 10 nanometers across, notes Supratik Guha. In comparison, the materials scientist explains, “a human hair is about 7,500 microns.” (A micron is one millionth of a meter; a nanometer is one billionth of a meter.) Guha works at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Ill., and at the nearby University of Chicago.

To see which fabrics worked best in blocking out aerosols, Guha and his colleagues performed tests. They set up a chamber to create aerosols of salt in the size range of the droplets that can carry the COVID-19 virus. A fan blew these aerosols toward tubes. A piece of fabric — sometimes layers of one or more types of fabric — covered the near end of each tube. The team then measured what share of the aerosols made it through the fabrics.

Overall, a combination of fabrics worked best. And not just any fabrics. The top performers paired 600-thread-count cotton (meaning 600 threads were woven to make up each square inch of fabric) with two layers of either silk or chiffon. On average, each type stopped at least 90 percent of the particles.

What does this mean if you make your own mask? “Use tighter fabrics with tighter weaves,” Guha says. A tighter weave has smaller holes for particles to sneak through. “Try to use combinations of materials,” he adds, “They filter the particles in different ways.”

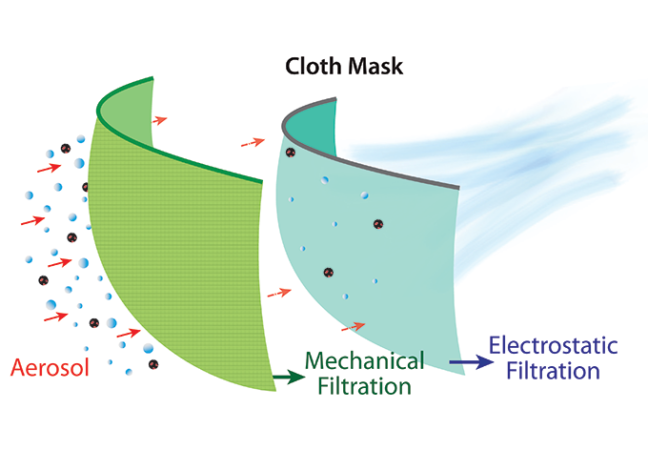

For example, tightly woven cotton works as a mechanical filter. Like a sieve, it keeps airborne bits that are too big from going through the holes between its threads. Chiffon or silk can work a second way, too. The structure of the molecules that make up those fabrics lets them attract electrons or give them up, Guha explains. That lets them attract charged aerosols. This electrostatic property lets the threads and aerosols bind to each other.

But don’t stress out if you don’t have exactly the right type of high-count cotton, silk or chiffon. A sample from a cotton quilt with batting also worked very well in the tests as did four layers of silk. The important lesson, Guha found, is that “there are simple materials available that work very well.” (And as the author of this story shows, making a mask out of them isn’t too challenging.)

Fit matters

But even the best fabric will not perform well, Guha says, if the mask doesn’t fit well. The goal is to limit leaks.

Any air that can leak through the sides, top or bottom of masks can carry virus-laden aerosols. To test the importance of such leaks, Guha’s team drilled tiny holes at the side of the fabric mounts. These created gaps of maybe 1 percent of the fabrics’ filtering area. Yet that small amount cut the filtering efficiency by at least 50 percent!

“What we did was not rocket science,” Guha notes. None of what his team learned, he says, “was really surprising. But we wanted good, solid data.” In other words, the team had a hypothesis. But until it was tested, the researchers couldn’t know for sure how well it might hold up.

The team reported its findings April 24 in ACS Nano.

The team’s work is an “excellent study that adds more to our understanding of cloth masks,” says Raina MacIntyre. She heads research on biosecurity at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. “The results confirm firstly that fit is important,” she says. “Even an N95 mask has vastly reduced efficiency if it does not fit.” (Medical workers wear N95 masks in high-risk situations).

Loretta Fernandez and Amy Mueller are environmental scientists at Northeastern University in Boston, Mass. They don’t usually study masks. But talk about masks during the current pandemic left them curious. So they used science to compare 10 types of homemade fabric masks to an N95 mask and to somewhat less protective surgical masks. Quips Fernandez, “We really just felt like we were working on a science fair project.”

They, too, set up a particle generator to churn out particles of salt. But instead of testing the masks on a solid stand, one of the researchers wore each mask. Separate counters measured the concentration of particles outside a mask and inside it. The sewn masks filtered out anywhere from around 30 percent to 70 percent of the particles.

Then the team tested the role of a snug fit on a mask’s performance. To do that, they used part of a ladies’ stocking. They cut across the leg of the stocking, creating a tube of stretchy nylon mesh. Then the researchers slid the tube over the head until it covered the mask being worn. This greatly improved the filtration of each mask.

A cotton mask with a cotton batting filter, for example, initially filtered out roughly 33 percent of the salt particles. After being held snugly in place with the nylon sleeve, it now kept more than 80 percent from moving through the mask. Fernandez and Mueller’s findings appear on the medRxiv website. (Their study has not yet been peer reviewed.)

Other filtration issues

Water resistance is also key, MacIntyre says, yet neither of the new studies addresses it. Moisture from exhaled breaths or sweat on the inside will make a mask uncomfortable. A bigger issue: “Masks that get soggy or allow liquid through will not protect well,” she notes, “no matter how well they filter [dry] air.”

Some people insert filters made of various materials into homemade masks. Consider the safety of breathing in any particles from those filters, Fernandez advises. The fact that something is safe for one type of use — such as a fabric softener sheet or a vacuum cleaner bag — doesn’t always mean it’s safe to breathe through.

Also key: You need to be able to breathe easily through a mask. A fabric like silk can be “very breathable,” Guha notes. It can be thin but still have a tight weave. And while some groups at high risk might try a stocking to get a tight fit, Fernandez says she just wears a mask on its own when she goes out. Otherwise, it can feel too tight and hot.

After all, she points out, a mask won’t protect you or others unless you wear it.