Scientist reports first gene editing of humans

The newborn twins could pass on their tweaked genes to future generations

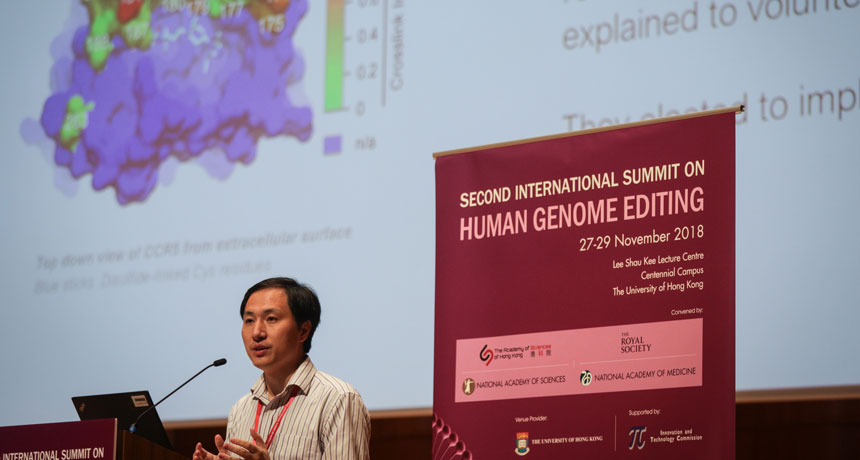

A Chinese scientist made a surprise announcement this week. It was just as an international conference to discuss human gene-editing was to begin. Jiankui He reported he had already done what these scientists would be talking about: He created the world’s first gene-edited babies. These twin girls are being called Lulu and Nana (not their real names).

On November 28, He offered more details to the scientists attending that conference. Lulu and Nana’s parents were one of seven couples recruited from a group of patients with HIV. That’s the virus behind AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). What’s more, at least one more woman from the group is pregnant with a gene-edited baby.

Reactions were swift. Most scientists condemned what He claimed to have done. Altering the genes in human embryos to create babies is premature, they said. It also threatens exposing the children to unneeded health risks, they added.

The announcement also points to a big new change in genetic research. This work doesn’t just repair a defect in some adult. It forever changes an individual’s DNA. Later, that edited DNA can be passed down to future generations.

He’s team is aware that the scientific community thinks that gene editing is still not safe or appropriate for use in human embryos, says Josephine Johnston. She is a lawyer and bioethicist at the Hastings Center. This research institute in Garrison, N.Y., focuses on bioethics — issues of whether certain biological research should be done, even when it’s possible to do.

The scientists involved in tweaking the babies’ genes “have knowingly violated the ethical norms surrounding this technology,” Johnston says. “You could even wonder whether they’re doing this for attention.”

But in a news interview with the Associated Press, and in a video posted November 25, He said his team had altered genes designed to cut the risk that either of the newborn twins could get HIV. This gene-tweaking was done on embryos in a lab dish. Those embryos were later implanted in the twins’ mom.

The resulting babies “came crying into this world as healthy as any other babies a few weeks ago,” He reported. Since February, this scientist has been on unpaid leave from the Southern University of Science and Technology of China. It’s located in Shenzhen.

Criticism came fast

Many researchers and ethicists expressed immediate outrage at He’s claim. They said the science behind this was too new to ensure gene editing of human babies was safe. Opponents also said the move could be seen as the first step in making “designer babies” — children edited to enhance their intelligence, athletic ability, hair color or other traits.

He rejects the term designer baby. He and his colleagues wrote a commentary that appeared online November 26 in the CRISPR Journal. “Call them ‘gene-surgery babies’ if one must or better yet ordinary people who have had surgery to save their life or prevent a disease,” the team said. But in his video, He said that he realizes his work will be controversial. He also said he’s willing to take the criticism. Some families need gene-editing to have healthy children, He said.

But he agreed that enhancing IQ or changing hair or eye color are “not things loving parents do.” He, too, maintains that those types of changes should be banned.

Yet He’s editing of the twin’s DNA was not lifesaving, argue many researchers and ethicists. It doesn’t even prevent disease. Although the girls’ father has HIV, there are safer ways than gene editing to protect someone from picking up the virus, they claim. And that makes tweaking the girls’ genes both unnecessary and unethical.

So far, He’s work has not been published in a scientific journal. Moreover, other researchers have not gotten access to any data or DNA samples that could confirm his new claim.

Researchers at the Hong Kong meeting who saw the talk aren’t convinced that He provided enough evidence to show the editing was successful and didn’t damage other genes. Earlier work by others has indicated that some cells in embryos may be incompletely edited or escape editing entirely.

Indeed, there would be no way to know if every cell in an embryo was edited equally without examining the DNA in each cell separately, says Dennis Eastburn. He’s a molecular geneticist who was not at the summit. Eastburn is chief science officer of Mission Bio. It’s located in South San Francisco, Calif.

Should the practice be stopped?

He performed his embryo-tinkering largely in secret. Not even the university where he worked had been aware of the study.

At least one prominent gene-editing researcher, Feng Zhang, has now called for a ban on gene-edited babies — at least until researchers can set requirements for how it can be done safely. Zhang works at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

Hundreds of Chinese scientists have also signed letters condemning He’s work. They called for greater oversight of gene-editing experiments, too.

Wensheng Wei works at Peking University in Beijing, China. At the Hong Kong meeting, Wei asked He why he had worked in secret and had undertaken what he knew was controversial work to create the babies. He didn’t answer.

Government leaders in China are also questioning the research. Shenzhen City Medical Ethics Expert Board issued a statement. It said the board would investigate. Documents describing the gene-editing work on the twins mentioned a hospital where it was done. That hospital now denies the work was done there.

He’s university said in a statement on November 26 that it too condemns his gene editing of babies. It said that research “seriously violates academic ethics and academic norms.” That university also said it will launch a probe into He’s new work.

Editing not needed by girls, critics argue

CCR5 is the name for a gene. It produces a protein that allows the most common version of the HIV virus to enter cells. Some people are born naturally with mutations — altered forms of this gene. Those natural mutations help guard against HIV infection in these people.

He and his team used the gene-editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 to disable the CCR5 gene in two fertilized eggs. Those eggs would develop into Lulu and Nana.

HIV infection is still a deadly disease. “Discrimination [against people with HIV] increases the devastation,” He said. Gene editing could spare such children from their parents’ fate, He said.

But the chance that Lulu and Nana would get HIV from their father when their mother doesn’t have the virus is “almost zero. In fact, probably zero,” says Anthony Fauci. He should know. Fauci is director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md.

The children could easily avoid HIV infection by other means, he says. So “to put them through the risk of editing their genes as embryos . . . in my mind, is inappropriate at best and unethical at worst.”

Fauci and others are concerned that gene editing could cause problems. It might damage other important genes, for instance. Such genetic harm might lead to cancer or some other health problems later in life. And the babies aren’t even guaranteed to escape HIV. People with defective CCR5 genes may still be infected with an uncommon form of HIV. And people with defective CCR5 genes are more susceptible to serious complications from infection with the West Nile virus, Fauci notes.

Even if Lulu and Nana don’t end up with any health problems, this experiment should not have been done, says Julian Savulescu. He is a bioethicist in England at the University of Oxford.

So far, no one has shown that He even did was he claims to have done. But if his claims are true, that work would be “monstrous,” says Savulescu.

He has argued in the past that parents may one day have a moral obligation to edit their children’s genes — if it can be done safely and would save their children from some grave illness. But the new experiment gave the babies no real health advantage, while putting them at risk of harm, Savulescu says. “It’s a bad scientific study.”

Editor’s note: Feng Zhang is on the board of trustees of Society for Science & the Public, which publishes Science News for Students.