Scientists discover how norovirus hijacks the gut

In mice, at least, this major stomach bug sickens by targeting a rare gut cell

Each year, bouts of norovirus — a stomach bug — cause misery in 19 to 21 million Americans. Scientists at last are homing in on how this nasty virus does its work.

vadimguzhva/iStockphoto

Stomach bugs sweep through schools and workplaces every year around the world. Norovirus is often the culprit. In the United States, this infection tends to strike from November to April. Family members can fall ill one after another. Whole schools can shut down because so many kids and teachers are out sick. It’s a very contagious disease that causes vomiting and diarrhea. Now, scientists have learned just how this nasty virus takes over the gut. New data in mice show that it homes in on one rare type of cell.

Norovirus is actually a family of viruses. One of its members emerged at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea. There, it sickened 275 people, including some of the athletes. Globally, noroviruses cause about 1 in 5 cases of gut-wrenching stomach illness. In countries where healthcare is good and easy to get, it’s mostly inconvenient. The viruses keep their victims home from work and school. But in countries where healthcare is more costly or hard to get, norovirus infections can prove lethal. Indeed, each year more than 200,000 people die from them.

Scientists had not known much about how these viruses do their dirty work. They didn’t even know what cells the viruses targeted. Until now.

Craig Wilen is a physician scientist at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Previously, his team had shown in mouse studies that to enter cells, noroviruses need a specific protein — molecules that are important parts of all living things. They used that protein to home in on the viruses’ target.

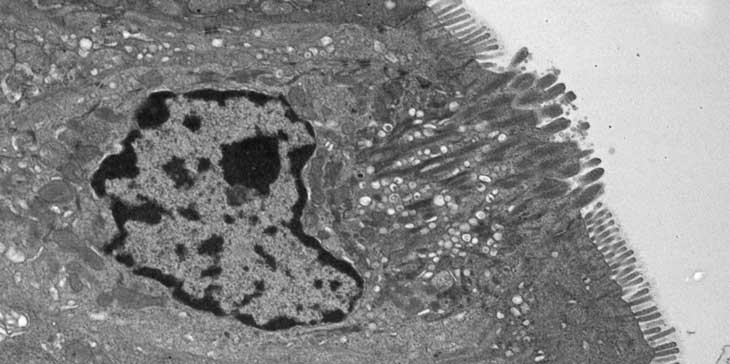

That key protein showed up on only one rare type of cell. It lives in the lining of the intestine. These cells stick tiny finger-like projections into the gut wall. This cluster of tiny tubes sticking off the ends of the cells looks like a “tuft.” That explains why these are known as tuft cells.

Story continues below image.

Tuft cells seemed like the prime targets for norovirus because they had the gate-keeper protein needed to let the virus in. Still, the scientists needed to confirm the cells’ role. So they tagged a protein on the norovirus. That tag caused the cell to light up when the virus was inside it. And sure enough, like beacons in a dark sea, tuft cells glowed when a mouse developed a norovirus infection.

If noroviruses also target tuft cells in people, “maybe that’s the cell type we need to be treating” to stop the illness, says Wilen.

He and his colleagues shared their new findings April 13 in the journal Science.

Tuft cells in tough guts

Identifying a role for tuft cells in a norovirus attack “is a significant step forward,” says David Artis. He is an immunologist — someone who studies how organisms ward off infections — at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. He was not involved in the study.

Scientists had already linked tuft cells in 2016 to one immune response. These cells turned on when they sensed the presence of parasitic worms. Those worms can live in the gut, feasting off the food flowing by. When tuft cells notice these intruders, they produce a chemical signal. It warns nearby tuft cells to multiply, creating legions big enough to fight off the parasite.

Research had also shown that the presence of parasites makes a norovirus infection worse. Perhaps the extra tuft cells that arise during a parasite infection are part of the reason. Uh oh. Wilen says these extra tuft cells seem to be “good for the virus.”

Finding out how norovirus tackles tuft cells may be important for more than just preventing a short-lived bout of vomiting and diarrhea. It might also help researchers who want to understand inflammatory bowel diseases. These chronic conditions inflame the gut — often for decades. This can cause intense pain, diarrhea and more.

Researchers now speculate that some outside trigger — like a norovirus infection — might be what ultimately turns on these digestive diseases. In one 2010 study, Wilen notes, mice with genes that make the rodents especially likely to develop an inflammatory bowel disease showed symptoms of that disease after being infected with norovirus.

The finding that norovirus infects tuft cells was “shocking,” Wilen says. This information could motivate a lot more research.

Norovirus is good at making many, many copies of itself during an infection. To do that, they must first hijack the copying “machinery” of the cells they infect. Norovirus will only hijack a tiny share of tuft cells. Studying why could help scientists better understand this scourge — and each year spare many people a lot of misery.