Scientists hide a real movie within a germ’s DNA

A tool called CRISPR helped store a galloping horse GIF in the DNA of bacteria

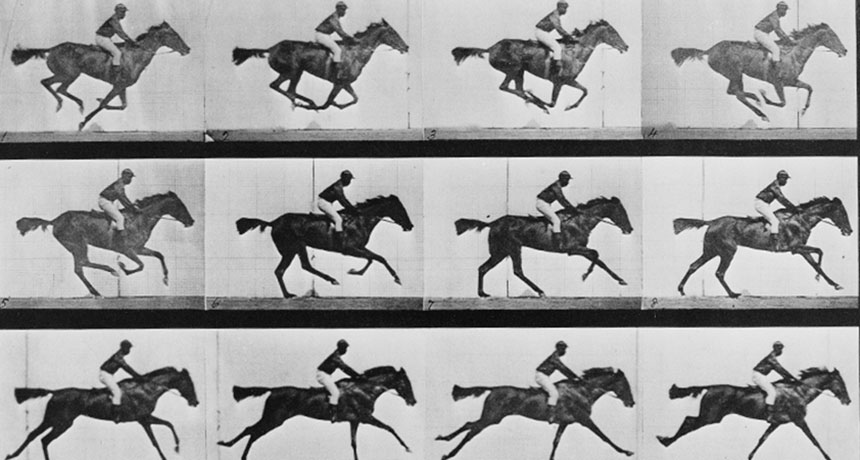

Pictures by turn-of-the-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge became an animation that scientists stored in bacterial DNA.

EADWEARD MUYBRIDGE/U.S. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

There’s a new movie that lasts only about one second and has no plot. Still, it’s generating a real buzz. That’s because scientists have stored this movie into the DNA of living bacteria.

Researchers stitched together the movie at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. They used a trendy tool called CRISPR (pronounced “crisper”), which edits genes. Those are the codes that direct a cell to make the proteins that do its work. The new editing tool is a molecular technology that lets scientists cut apart DNA and paste it back together — usually in a new way. This changes the code in those genes, and therefore what they do.

CRISPR has already helped researchers stop disease-carrying mosquitoes from breeding. Last year, Seth Shipman and his colleagues at Harvard recorded bits of information. Then they used CRISPR to splice it into the DNA of E. coli bacteria.

Now, this team is taking things a step further. It encoded images in bacterial DNA of a human hand, as well as of a short movie. That movie was a GIF of a galloping horse. Its five frames were images by famous turn-of-the-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who took pictures of animals and people in motion.

The researchers stored the moving images as nucleotides. Those are molecules within DNA that come in four types, called A, C, T and G. They’re the alphabet of DNA. And the order of those letters serves as a kind of code that holds an organism’s genetic instructions.

(Story continues below image)

For their latest work, the scientists created a new code. It holds the instructions for coloring the pixels, or small squares, in the black-and-white images they wanted to store. Strings of three nucleotides stood for 21 different shades, ranging from black to white. The team encoded the video — frame by frame — in nucleotide sequences they made in the lab. Then they used CRISPR technology to paste the new sequences into the genes of E. coli bacteria.

The scientists grew the bacteria for several generations. Then they peered into the DNA of the newest bacteria. From these DNA, they were able to read, and reconstruct, the images and movie. About 90 percent of the encoded information had survived.

Shipman and his colleagues shared their results July 12 in Nature.

It’s not a perfect storage system. But the results show how CRISPR could help hide data in the genetic blueprints of bacteria. The study is part of a larger effort to use DNA to store data — from audio recordings and poetry to entire books. Maybe it could even store a recipe for some popcorn to go with that movie.