Searching for alien life

A robot rover practices looking for alien life by trekking across the world's driest desert.

By Emily Sohn

On a clear night, go outside, lie on your back, and stare into the sky. As you gaze at the multitude of stars, you might wonder: Is there life on other planets out there?

“That’s one of the great questions of humanity,” says David Wettergreen. He’s a robotics scientist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

“Are we alone or not?” Wettergreen asks. “You can spend your whole life pondering this question.”

Instead of just thinking about the question, Wettergreen wants to answer it. And he’s getting funds from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to help find an answer.

The space agency has a project called the Astrobiology Science and Technology Program for Exploring Planets (ASTEP). Astrobiology is the study of life in the universe. One way that NASA researchers have looked for signs of life in outer space is by sending signals into the void and listening for a response. So far, these messages have turned up nothing but silence.

Wettergreen has a different strategy, and it begins right here on Earth. Earlier this month, he and his team traveled to one of the driest, most desolate places on the planet—the Atacama Desert in northern Chile. Conditions there are similar to conditions on Mars. And, because the landscape is so dry, scientists argue about whether any sort of life could possibly survive in the desert on its own.

|

|

A view across the desolate Atacama Desert in Northern Chile.

|

| Carnegie Mellon University |

In the Atacama, Wettergreen and a team of researchers use an equipment-loaded robot to search for pockets of life. The scientists want to learn if, how, and why anything can survive in such harsh conditions.

“Our ultimate goal is to discover something unique about the Atacama,” says Wettergreen. In a broader sense, he says, the techniques used on the mission could eventually help astrobiologists explore other parts of the solar system.

“We’re trying to learn about the desert,” Wettergreen says, “and about how you go looking for life.”

The 3-year project is now in its second year. You can follow the current expedition and view images from the robot rover on the Web at http://www.frc.ri.cmu.edu/atacama/ (Carnegie Mellon University).

Roving robot

The team’s most valuable member is not a person. It’s a robot named Zoë. Zoë happens to be the Greek word for “life.”

Zoë is about the size of an office desk. It’s 1 meter high and 2 meters wide, and it weighs about 180 kilograms. Its top speed is 1.2 meters per second. It carries an array of solar cells on its back to collect energy from the sun.

|

|

The robot rover Zoë is about 1 meter tall and 2 meters wide. It weighs 180 kilograms.

|

| Carnegie Mellon University |

The robot is similar to the rovers Spirit and Opportunity, which are currently on Mars. The scientists give Zoë a general program telling it what to do. The vehicle then explores the landscape. As it cruises around, Zoë sends data back to the researchers. Nobody drives it, and there’s no remote control.

Using a robot allows the researchers to take frequent measurements over a large area, creating a sort of catalog of what’s out there.

Last year, the team spent about a month in the Atacama just developing and testing instruments for Zoë. The robot carries three sophisticated cameras that record everything in very clear, color images. To mimic the 3-dimensional view that a person would have while walking around, the cameras sit close to each other just above eye-level.

To detect microscopic life on the ground, Zoë carries a fluorescence imager.

Fluorescence occurs when a substance absorbs certain kinds of electromagnetic radiation, such as ultraviolet light or x-rays, and gives off visible light of a particular color in return. As soon as the ultraviolet light or other source is turned off, the substance stops giving off visible light.

Because different materials absorb and give off different colors of light, Zoë can detect and distinguish between various kinds of minerals and molecules.

|

|

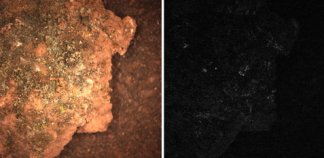

A rock (left) contains certain minerals and other substances that fluoresce, or give off light, at certain wavelengths (right), allowing them to be identified.

|

| Carnegie Mellon University |

Zoë also carries a spectrometer, which analyzes how objects in the soil reflect light. The spectrometer detects which particular colors, of wavelengths, of visible and infrared light are reflected by soil particles. Like fingerprints, particular patterns of wavelengths correspond to different minerals.

The robot also has a plow that can turn over rocks and dig into the soil, allowing the fluorescence imager and spectrometer to examine what’s under the surface.

Field life

Even though the robot does much of the work during the research mission, life in the field isn’t easy for the researchers. “We work from dawn until dusk, 7 days a week,” Wettergreen says. The scientists and technicians have to make sure that Zoë is working correctly, and they must sift through loads of data transmitted by the robot.

|

|

Camping out in the desert with Zoë.

|

| Carnegie Mellon |

The environment can be hard to adjust to. Less than a centimeter of rain falls on the Atacama every year. A bone dry, rocky landscape stretches as far as the eye can see. There are no trees, no lakes, no little animals scurrying around. The only contrast is the brilliantly blue, cloudless sky above.

|

|

Atacama’s mixture of dirt and rock. An ordinary pen gives you a sense of how large the pebbles are.

|

| Carnegie Mellon University |

“In the Atacama, you see rock and soil in all directions and really nothing else,” Wettergreen says. “When you look up, it’s blue. When you look down, it’s brown. With the midday sun overhead beating down on you, it does seem desolate.”

Still, Wettergreen and his colleagues are convinced that there is more to the Atacama than meets the eye, and they’re determined to prove it.

“We are finding that the desert is not uniform,” he says. “There are microhabitats, small oases. Sometimes a single rock provides shelter or a trap for moisture.” Water is often the first sign that there might be life around.

If Zoë finds good ways to look for these hidden specks of life, scientists might eventually make similar discoveries on Mars and beyond. That would answer one of life’s biggest questions, and stargazing would gain a whole new meaning.

Going Deeper:

Atacama Facts

|

|

The Atacama Desert in northern Chile.

|

| Carnegie Mellon University |

The Atacama Desert in northern Chile is less than 100 miles wide and about 600 miles long. It’s located between the Pacific Ocean and the Andes Mountains.

The Atacama is made up mainly of salt basins, sand, and lava flows.

Unlike other deserts, the Atacama is quite cool, with average daily temperatures ranging from 0 to 25 degrees Celsius.

The area gets an average of less than 0.004 inch (or 0.01 centimeter) of rain per year.