Seen on the Science Fair Scene

At science fairs, students get to travel the world, gain research experience, and make new friends. Oh, yeah, and then there are the prizes.

By Emily Sohn

Every spring, more than 1,000 high school students from around the world compete for millions of dollars in scholarships and other prizes at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). But prizes aren’t the competition’s only draw.

Science projects are great opportunities to build real-life research experience. And once students experience science fair success, they have opportunities to travel. Along the way, they make friends whom they often see from one competition to the next.

At the 2007 ISEF in Albuquerque, N.M., for example, 25 of the 1,500-plus participants were once finalists in the Discovery Channel Young Scientist Challenge (DCYSC), which is held in Washington, D.C. every fall.

|

|

Nick Ekladyous (far left) and teammates explored Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity at the DCYSC in 2004.

|

| Richard Cho, DCYSC |

At DCYSC, 40 of the nation’s top middle school science students work in groups to tackle challenges with a scientific theme. They are judged on their problem-solving, teamwork, and communication skills.

Their experiences at DCYSC, say these 25 science fair veterans, have served them well at ISEF.

“DCYSC helped us learn how to present our ideas to adults,” says Sasha Rohret, a 17-year-old senior at the Keystone School in San Antonio, Texas.

|

|

At ISEF 2007, Sasha presented the results of her ongoing research on the possibility of growing plants on Mars.

|

| Emily Sohn |

“I [also] got a lot of experience with the scientific method,” she says. “I had to work in groups with people I didn’t know.”

From science fairs to Mars

At this year’s ISEF, Sasha presented the results of her 4-year (and counting) study that explores the possibility of growing plants on Mars. She got the idea after seeing a television program about the Mars rovers, robotic spacecraft that landed on the Red Planet in 2004. Sasha was an eighth-grader at the time.

The program said that if people ever wanted to live on Mars, they would need to learn how to grow food there. The idea captured Sasha’s imagination, and her work on the subject has already earned her one trip to DCYSC and three trips to ISEF.

For her experiments, Sasha has grown plants in volcanic soil that resembles Martian soil. She puts the plants in airtight, gas-filled tanks that mimic the atmospheres of Mars and Earth.

|

|

Over 4 years of research, Sasha has meticulously measured how plants might grow on the Red Planet under a variety of soil and atmospheric conditions.

|

| Courtesy of Sasha Rohret |

Over the years, she has discovered that the relatively large proportion of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the Martian atmosphere is the biggest obstacle to growing plants there. The gas makes up about 97 percent of Mars’ atmosphere, compared with less than 0.05 percent of the atmosphere on Earth.

Mars’ atmosphere is also thinner than Earth’s, so more of the sun’s radiation hits Mars’ surface, Sasha says. Extra radiation is tough on plants.

“You would have to alter the Martian atmosphere quite a bit to grow plants on Mars,” Sasha concludes. However, she remains optimistic. “I think it will happen.”

Some day, Sasha would like to be an astrophysicist—an astronomer who specializes in the physical and chemical properties of objects in outer space. And if she ever gets an invitation to explore Mars, she’ll leap at the chance.

“I would go if I had the opportunity,” she says. “I think it would be pretty fun.”

Science students to the rescue

The science fair veterans in Albuquerque tackled a diverse range of subjects, from botany to mechanical engineering. One thing that many of the projects had in common was their attempt to solve important, real-world problems.

“I always try to do a project every year that will impact society in a positive way,” says Nicholas Ekladyous, 15, now a senior at Cranbrook Kingswood Upper School in Bloomfield Hills, Mich.

|

|

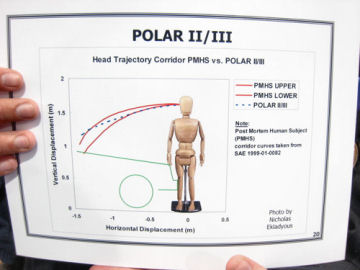

At ISEF this year, Nick stood with a crash-test dummy and presented his work on van safety.

|

| Emily Sohn |

For his eighth- and ninth-grade projects, Nick aimed to make 15-passenger vans safer. He built a scaled-down model of such a van and then designed a computer program to predict when a real van would be most likely to roll over. The 2-year project earned him a trip to DCYSC in 2004 and to ISEF in 2005.

As a sophomore in 2006, Nick attended ISEF with his design of a safer material for padding playground floors. Finally, for ISEF 2007, Nick used computer models to develop a design for car hoods that would be less harmful to pedestrians struck in traffic accidents.

“If pedestrians are hit, the chances of death are very high,” Nick says.

|

|

For his 2007 ISEF project, Nick created a computer program to model how badly pedestrians would be injured when struck by cars with a variety of hood designs.

|

| Emily Sohn |

According to Nick, his hood would reduce death and injury to pedestrians by as much as 70 percent compared with current models. He has filed for a patent on his design.

Lessons learned

The exhibition hall at ISEF can be an intimidating place, filled with row after row of projects with hard-to-pronounce names. Still, the DCYSC veterans seemed to be enjoying the scene—sometimes to their surprise.

|

|

In the exhibit hall at ISEF each year, more than 1,500 students display the results of work that touches on nearly every topic in science.

|

|

Intel

|

“DCYSC was the first time I got to go to a national competition,” says 16-year-old Lucia Mocz, who conducted her first science fair project in middle school only because it was a class requirement. Lucia is now a junior at Mililani High School in Hawaii.

“That was a major force in getting me interested in science,” she says. “I did not like science before, but [DCYSC] was just so fun. Now, I want to major in math.”

|

|

Designing projects for science fairs helped 16-year-old Lucia discover a love of math.

|

| Emily Sohn |

Want to experience the science fair scene? First, find a topic you’re passionate about, suggest the DCYSC/ISEF veterans. Then, let the investigations begin.

Going Deeper: