Several plant-like algae can morph into animal-like predators

Scientists turn up new types of green algae that can develop a taste for bacteria

A community of green algae belonging to a Chlorella species. Some of its “cousins” were among those shown to turn predatory when unable to use the sun for energy.

Sinhyu/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Laura Allen

Many green algae are made of single cells. They tend to spend much of their day soaking up sunlight, turning it into energy. These swimming plankton appear plant-like. Unless, that is, one gobbles up a nearby bacterial cell. Now it has become an animal-like predator.

When ecologist Eunsoo Kim first witnessed this back in 2013, she was shocked. Until then, she and other scientists had thought the sun provided all the energy green algae need. They are green, in fact, because they contain chlorophyll. Just as in plants, these algae use chlorophyll to derive energy from the sun through photosynthesis.

But seeing some algal cells dine on bacteria upended this worldview. Now, Kim and her team at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City show that the first bacteria-eating algae they found were hardly unique. They have turned up five more oceanic species that do the same thing.

Kim’s group shared its latest findings March 2 in The ISME Journal. The journal specializes in microbial ecology.

Some green algae “combine both a plant-like lifestyle, through photosynthesis, and an animal-like lifestyle, through predation,” explains Sophie Charvet. “These special algae can swallow whole bacteria and digest them.” Charvet is a postdoctoral scientist who helped carry out the new experiments.

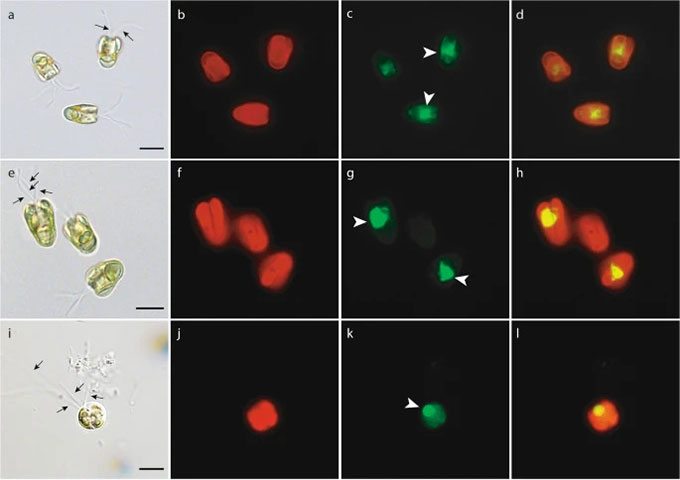

The algae and bacteria are both very, very small. To study how and when algae turn predatory, the researchers employed a trick. They treated the bacteria with a harmless fluorescent dye. It glows green under ultraviolet (UV) light. Dying the bacteria proved tricky. Recalls Charvet, “We had to repeat the experiment too many times to count!”

Next, they put the bacteria and algae in the same water. If the algae glowed under UV light, this would show they had dined on the bacteria. And they saw this indeed happened with a second species of green algae. Excited, the researchers began testing others.

The bacteria aren’t always appetizing

Soon the algae started causing problems. Sometimes they wouldn’t eat. Other times it took far longer than usual for them to turn fluorescent. What was going on?

This is when the museum team learned the algae didn’t view bacteria as a preferred snack. In fact, the algae showed little interest in eating microbes when conditions for photosynthesis were good.

“This means that their ‘animal’ behavior is a mechanism they use to survive in situations when they cannot live as ‘plants,’” Charvet explains. Along the way, her team also learned these algae are even pickier. They want their prey alive.

Ben Ward is a plankton ecologist. He works at the University of Southampton in England. He isn’t surprised to learn there are multiple types of bacteria-eating algae in the sea. He’s more impressed by how the museum team found them. They identified likely candidates, he notes, “through genetic profiling.”

In earlier work, Kim identified genes that seemed special to many types of bacteria-eating organisms. For the new study, her team looked for these genes in other species of green algae. The presence of those genes suggested these algae, too, might turn predatory at times.

Charvet points out that green algae are important to study. Those “in the oceans are responsible for half the oxygen in our atmosphere,” she says. “Despite their small size,” she says, “they are just as important to our survival as the Amazon forest and all other forests combined.”