The Shape of the Internet

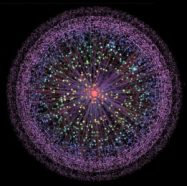

The web of connections that makes up the Internet looks a lot like a medusa jellyfish.

By Emily Sohn

The Internet is really good at connecting people, and Science News for Kids is a perfect example. I live in Minneapolis. My editors work in Chicago and Washington, D.C. And you can look at this Web site on computers all over the world.

It seems so simple, but the Internet is a complex web of connections. And that web looks a lot like a medusa jellyfish, according to new research by scientists in Israel. Within the Internet, they say, there is a dense core of connections surrounded by lots of tentacle-like links.

Until now, scientists have had a hard time mapping the structure of the Internet. That’s because it formed almost by accident in the 1960s and 1970s, when universities, government agencies, and companies first decided to link their computer networks so that they could share information.

The Internet grew as new groups added their computer systems to the structure. Today, when you send an e-mail to a friend next door, it can pass through as many as 30 small networks—or subnetworks—before it arrives at its destination just a split second later.

Researchers have tried to understand the shape of the Internet before. Their attempts have involved software that sends packets of information to specific destinations and tracks their routes. The packets work like probes, revealing details about which subnetworks they travel through on their way.

But until recently, scientists were able to send probes from only a small number of sites, usually at universities in the United States. With such a limited number of starting points, the information stayed close to home. The probes missed more distant sites and links.

This has been such a big problem that “there was a growing opinion before [the new] study that you really couldn’t measure the Internet,” says Scott Kirkpatrick of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Kirkpatrick and his colleagues, however, found a way. They enlisted volunteers to help them send probes from more than 12,000 computers around the world. Following these probes, the scientists counted how many routes connected each subnetwork to the others.

This widespread method revealed three layers within the Internet. At the core of the virtual jellyfish are about 100 of the most tightly connected subnetworks. These include some subnetworks you’ve probably heard of, such as Google.

Surrounding this core is a much larger group of subnetworks that have lots of connections to each other and to the core. Finally, about one fifth of the Internet’s subnetworks can communicate to the rest of the world only by sending information through the core. The scientists compare these fringe subnetworks to the tentacles of a jellyfish.

Because 80 percent of subnetworks can reach each other without going through the core, the new map suggests that the Internet is less vulnerable than scientists previously thought. Attacks or outages to any one part of the Internet probably wouldn’t take out the whole system.

Your access to Science News for Kids, in other words, should be safe, no matter where you live.—Emily Sohn

Going Deeper:

Rehmeyer, Julie J. 2007. Mapping a medusa: The Internet spreads its tentacles. Science News 171(June 23):387-388. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20070623/fob2.asp .

Sohn, Emily. 2006. Internet generation. Science News for Kids (Oct. 25). Available at http://www.sciencenewsforkids.org/articles/20061025/Feature1.asp .