Silk can be molded into strong medical implants

The trick is to first freeze-dry it and turn it into a powder

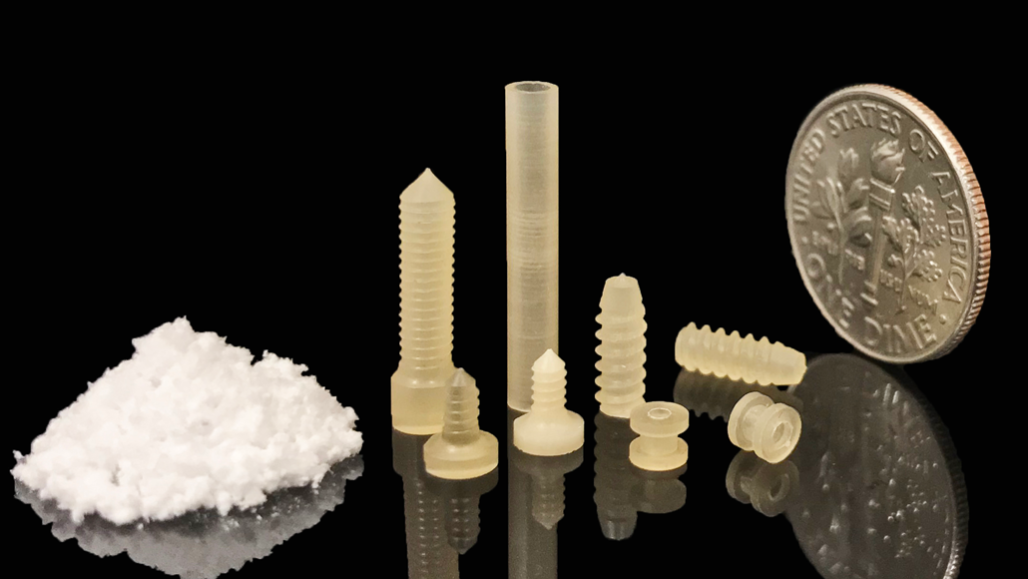

Powdered silk (left) can be molded into a variety of medical implants, including screws to help hold the pieces of broken bone together (several at center).

Chunmei Li and David Kaplan/Tufts University

By Sid Perkins

Silk is a marvelous material with a long history and has many uses. People have been weaving silk fabrics for more than 5,000 years. Doctors have been using it to sew wounds shut for more than 1,800 years. Now, biomedical engineers are using it to make different types of medical implants. A new approach will make it much easier and cheaper for innovators to build such devices.

Many sorts of animals produce silk. Some mussels use it to attach themselves to rocks. Spiders spin silk webs to trap their prey. The type of silk that’s most useful to people comes from what are often called silkworms. But silkworms aren’t worms. They’re actually the caterpillars of the domestic silk moth, Bombyx mori. Each caterpillar spins a cocoon before it becomes a pupa. That cocoon is woven from a silk fiber hundreds of meters (yards) long.

Doctors like silk for a variety of reasons, says David Kaplan. He’s a biomedical engineer at Tufts University in Bedford, Mass. For one thing, he notes, silk is a natural material that will break down in the body over time. So any implanted parts made of silk don’t have to be removed by surgery. Plus, not many people are allergic to it. So it is generally safe to implant parts made of silk.

One problem, though, is that the materials used to make silk parts don’t have a long shelf life, says Kaplan. Those materials are made of proteins called silk fibroin (FY-broh-in). They are what’s left behind when chemists remove a gummy substance called sericin (SEHR-eh-sin) from silk fibers. Silk proteins are typically kept dissolved in water until needed. But like all proteins, they can break down over time.

There’s another problem, too. All that water adds a lot of weight and volume to the silk materials as they’re stored. And that makes those materials expensive to ship from one place to another.

From fiber to powder

Kaplan and his colleagues set out to solve those problems. They began the process the same way, by removing sericin from silk fibers. From that point on, they did things differently. First, they dissolved the silk proteins in a solution with high levels of a salt called lithium bromide. Next they added water to dilute the mixture. Then they froze it with liquid nitrogen. Afterward, they put the icy mix into a chamber where the air pressure was very low. That combination of very low temperature and pressure triggered water to evaporate. (Called freeze-drying, this process often is used to make instant coffee and other food products.)

Finally, the researchers ground the freeze-dried material into a powder. The powder particles measured between 30 nanometers (a little over one-millionth of an inch) and 1 micrometer (40 millionths of an inch) across.

“This is a totally different way of processing silk,” says Chris Holland. He’s a scientist who works with natural materials at the University of Sheffield in England. He did not take part in the new research.

Kaplan and his team found they could mold really strong parts from the silk powder. They shaped the parts at high pressure, more than 6,400 kilograms per square centimeter (some 91,000 pounds per square inch). They also tested different heating temperatures. The silk parts were strongest when molded at a temperature of 145° Celsius (293° Fahrenheit). These powdered-silk parts were stronger than ones made the previous way, with dissolved silk proteins. They were even stronger than wood.

Kaplan and his team reported their development in the January Nature Materials.

Many different sorts of medical implants can be made from powdered silk, notes Kaplan. That includes screws used to hold a broken bone together. It also includes small tubes used to drain fluid buildup from an infected ear. Engineers might even add enzymes to ensure the molded parts break down over time. That would avoid needing surgery to remove them after their job is done.

Scientists describe as “biocompatible” any materials that can be used in the body without causing harm. “The fact that [powdered silk] is biocompatible is the icing on the cake,” says Holland. And that suggests to him another possible use: Embedding the molded implants with drugs (such as infection-fighting antibiotics or cancer drugs). The implants could slowly release a drug over time. That way, patients might not need to take pills or get painful injections.

Powdered silk is easy to work with too, says Kaplan. It is chemically stable and can last up to two years on the shelf. Plus, it’s lightweight because a lot of the water has been removed. So it doesn’t cost as much to ship the material from place to place.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.