A skeleton named ‘Little Foot’ causes big debate

Researchers disagree over whether the fossil hominid belongs to a new species

Paleoanthropologist Ron Clarke excavates the skull of a skeleton called Little Foot. This adult female hominid lived in southern Africa nearly 3.7 million years ago. Researchers can’t agree on what species she belonged to.

University of the Witwatersrand

By Bruce Bower

More than 20 years ago, a skeleton called Little Foot turned up in a South African cave. The nearly complete skeleton was a hominid, or member of the human family. Now researchers have freed most of the skeleton from its stony shell and analyzed the fossils. And they say 3.67-million-year-old Little Foot belonged to a unique species.

Ronald Clarke and his colleagues think Little Foot belonged to Australopithecus prometheus (Aw-STRAAH-loh-PITH-eh-kus Pro-ME-thee-us). Clarke works at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. As an paleoanthropologist, he studies fossilized humans and our relatives. The scientists shared their findings in four papers. They posted them at bioRxiv.org between November 29 and December 5. Scientists have suggested the species A. prometheus might exist. But many researchers have challenged that claim.

Clarke, however, has believed in that species for more than a decade. He found the first of Little Foot’s remains in 1994. They were in a storage box of fossils from a site called Sterkfontein (STARK-von-tayn). People began excavating the rest of the skeleton in 1997.

Many other researchers instead argue that Little Foot likely belonged to a different species. This hominid is known as Australopithecus africanus. Anthropologist Raymond Dart first identified A. africanus in 1924. He was studying the skull of an ancient youngster called the Taung Child. Since then, people have turned up hundreds more A. africanus fossils in South African caves. Those include Sterkfontein, where Little Foot was found.

The braincase is the part of the skull that holds the brain. And researchers found a partial braincase that Dart thought belonged to a different species in Makapansgat, one of those other caves. In 1948, Dart called this other species A. prometheus. But Dart changed his mind after 1955. Instead, he said that braincase and another fossil at Makapansgat belonged to A. africanus. There was no A. prometheus after all, he concluded.

Clarke and his colleagues want to bring back the rejected species. They say Little Foot’s distinctive skeleton, an adult female that is at least 90 percent complete, is solid evidence for it. Says Clark: “Little Foot fits comfortably in A. prometheus.”

The scientists estimated the ages of Little Foot and other fossils from Sterkfontein and Makapansgat. Based on those ages, Clarke says A. prometheus survived for at least one million years. And, he adds, this species would have lived along with the younger A. africanus for at least a few hundred thousand years. The new papers will appear in an upcoming issue of the Journal of Human Evolution. The journal will also publish several other new analyses of Little Foot’s skeleton.

Walking into an argument

Still, the team’s claims remain controversial. The papers “fail to make a sound case” for a second Sterkfontein species, says Bernard Wood. He’s a paleoanthropologist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Two other paleoanthropologists agree. They’re Lee Berger at the University of the Witwatersrand and John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Their comments will be published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. These researchers argue that Dart was right to get rid of A. prometheus. He never showed a clear difference between that species and A. africanus, they say. “I’m keeping an open mind, but I haven’t seen data [in the papers] to support any grand ideas about Little Foot,” Hawks says.

Clarke says Little Foot does have skull features that set it apart from A. africanus. He and a Witwatersrand colleague, Kathleen Kuman, describe those features in one new study. They point to the sides of Little Foot’s braincase. They’re more vertical than the sides of the one in A. africanus. And Little Foot has heavily worn teeth, from the front of the mouth to the first molars. That suggests Little Foot ate tubers, leaves and fruits with tough skins, Clarke says. A. africanus, in contrast, ate a larger variety of foods, he adds — ones that were gentler on teeth.

Robin Crompton works the University of Liverpool in England. He is an evolutionary biologist who led a second new study. It found that Little Foot had humanlike hips. And her legs were longer legs than her arms. That’s also a humanlike trait and hints that Little Foot walked upright. Such features are most similar to a 3.6-million-year-old skeleton dubbed Big Man. That skeleton, from East Africa, belonged to the species Australopithecus afarensis. The researchers think the ability to walk upright may have evolved at the same time in different parts of Africa.

Little Foot walked well but also was a good tree climber, the researchers say. She might have moved across tree branches upright while lightly grabbing branches with her arms for support. This is similar to how orangutans move. Crompton thinks this upright movement through trees later evolved into full-time, two-legged walking.

Owen Lovejoy led the analysis of Big Man’s skeleton. He’s a paleoanthropologist at Kent State University in Ohio. Lovejoy doubts that Little Foot did much walking across tree branches. And he disagrees with Crompton’s idea of how upright walking evolved. Big Man and Little Foot had bodies built for upright walking, he thinks. And they would have walked on the ground, not through trees.

Lovejoy says that one of the new papers supports his idea. That paper shows that Little Foot fell from a short height as a child. This caused a bone-bending forearm injury. (Clarke was an author of that study.) The injury would have made it hard to climb trees. If Little Foot was able to survive into adulthood with this arm injury, upright walking must have been especially important to her species, Lovejoy says.

Small brained woman

Carol Ward is a paleoanthropologist at the University of Missouri in Columbia. She predicts that more studies of Little Foot’s body parts will help to resolve these debates about her way of life. Yet another new study has just come out in the January Journal of Human Evolution. It focused on Little Foot’s brain size.

Amélie Beaudet is a paleoanthropologist at the University of Witwatersrand. She and her colleagues used scanning technologies to help a computer make a 3-D reconstruction, or digital cast, of Little Foot’s brain surface. They then compared it to similar digital casts of 10 other South African hominid specimens. Those fossils were between roughly 1.5 million and 3 million years old.

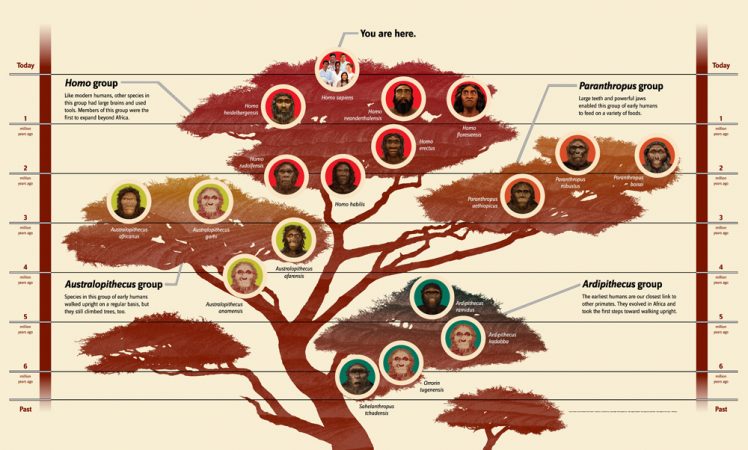

Little Foot had a small brain. Hers was only about one-third the volume of a modern adult woman’s, the new analyses show. In fact, Little Foot’s was more chimplike than was the brain of any other southern African hominid. That’s not surprising, the investigators add: Little Foot is also the oldest known southern African hominid.