Sky Dust Keeps Falling on Your Head

Dust raining down from space and Earth's atmosphere provides information about weather patterns, pollution, and the origin of the universe.

By Emily Sohn

Any time you go outside, you get pummeled by invisible storms of dust. Even on a perfectly sunny day, you inhale pieces of dead bugs. Floating specks of hair and pollen settle on your skin. Tiny chunks of comets might even fall on your head from outer space.

“Every time you sit on a bench, you’re sitting on cosmic dust,” says astronomer Don Brownlee from the University of Washington in Seattle. In fact, 6 million pounds of space dust settle on the planet every year, he says. “If you’re outside during the day, you’re probably going to get hit by a couple of things.”

You might never notice the stuff falling all around you. But some scientists collect cosmic dust and other kinds of floating particles to learn about weather patterns, pollution, and the origin of the universe.

Down to Earth

And now a new project is bringing sky dust studies down to earth: Maybe someday soon even you can help.

Studies of outer space have traditionally involved lots of expensive equipment. Brownlee and his colleagues, for example, send hi-tech airplanes more than 65,000 feet above Earth’s surface. The aircraft fly at three-quarters the speed of sound for 50 hours or so, collecting cosmic dust on a sterile filter about the size of a deck of cards.

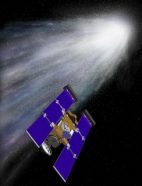

About half of what they pick up are micrometeorites—pieces of comets and asteroids about as wide as a human hair is thick. Back on Earth, the scientists analyze the space dust as a window into the past.

Meteorites are the only records we have of the origin of the universe, Brownlee says. “They date back in time to when the sun and Earth formed 4½ billion years ago.”

It will be the first mission to collect material from space since astronauts brought moon rocks back in 1972.

Brownlee hopes the Stardust mission will bring back useful information about our own planet, too.

“The Earth was 100 percent made from things that came in from space,” Brownlee says. “By looking at things that are still in space, we can look at things that participated in the formation of the Earth.”

Blowing in the wind

But we can learn just as much by looking at what’s already here, says Dan Murray, a geologist at the University of Rhode Island. His new project invites kids, teachers, and other interested people to contribute to a worldwide study of everything that’s blowing in the wind, including cosmic dust.

Along with Jim Sammons, a retired high school science teacher, Murray is gathering a network of sites around the world, where people will collect samples of sky dust, analyze it, and send their results to a public Web site: http://www.skydust.org/ .

Sky dust can reveal all sorts of interesting things about global weather patterns and pollution, Murray says.

In Rhode Island, for example, the researchers have collected Mongolian dust that drifted all the way across the Atlantic Ocean. In another case, kids who lived east of Lake Michigan traced twice-monthly onslaughts of carbon soot back to pollution-spitting barges on the lake.

With just a basic microscope, a good guidebook, and a little practice, anyone can tell the difference between different kinds of dust, pollen, even micrometeorites, Murray says. A fancier microscope reveals even more details.

If enough schools sent in data about the kinds of bugs, pollen, and other particles falling in their area, they might be able to help scientists track pollution, predict buggy seasons, measure meteor showers, or detect signs of global climate change.

Earth’s health

Those are all important clues about the overall health of the planet, Murray says. “Kids across the country could become the early-warning systems for looking for things that might not be good that are happening to this or that part of the planet.”

And while the Stardust mission is expensive and far away, the Skydust project will give real kids the chance to do real science.

“You don’t really know the answers, and that’s the exciting thing,” Murray says.

Jim Sammons agrees: “Just throw away the textbook, and right away the horizon becomes clear.”