‘Smart’ sutures monitor healing

Simple threads turned into sensors can relay what’s going on under a bulky bandage

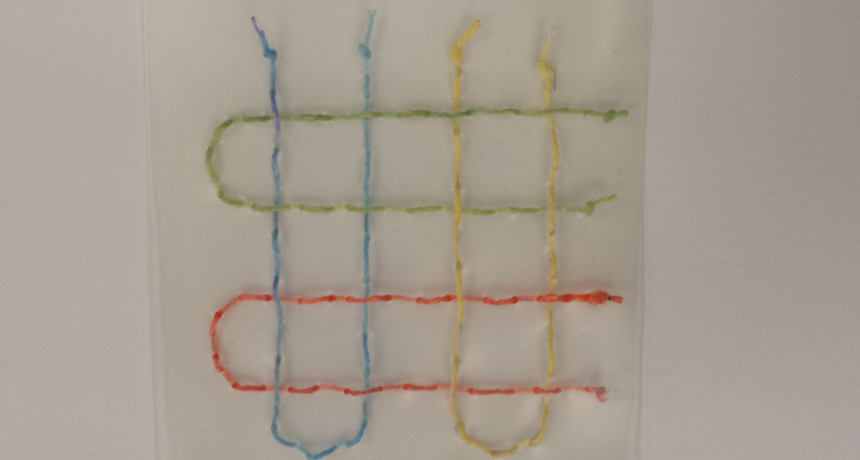

Researchers have developed coatings that transform simple threads into high-tech “smart” sutures that can monitor body temperature, pH and other aspects of a wound that’s been stitched together.

Mostafalu et al/Microsystems & Nanoengineering 2016

By Sid Perkins

After a doctor stitches up a gash or other cut, the wound usually gets a bandage. But that covering blocks the view of the wound as it heals. And that can be a problem if the gash gets infected. The problem may not signal when treatment is needed. Now, researchers have developed “smart” sutures that can alert caregivers when problems emerge. Future versions might even be able to deliver drugs to help a stitched-up wound heal.

Sutures are the threads used to close up a wound. They are pretty low tech. In many cases, they’re made of natural materials such as cotton or silk. In others, they’re made from a form of plastic. Some are even made of materials that dissolve in the body over time. (Those don’t require a return visit to have the doctor take them out.) Regardless of what they’re made from, however, their purpose is the same. They hold large wounds or incisions together so that they can heal.

But sometimes wounds don’t heal properly. Tissues can swell and bulge, causing the sutures to tighten. That can create an ugly scar. Or, the wound may become infected. That causes the tissue to redden and heat up. If these things don’t cause pain, the infection may hide out as it builds to a dangerous degree beneath a bulky bandage, says Sameer Sonkusale. He’s an electrical engineer at Tufts University in Medford, Mass. So he and his teammates figured out a way to transform sutures into sensors. These special stitches can report what’s going on beneath a bandage. They even can send out health dispatches from inside the body.

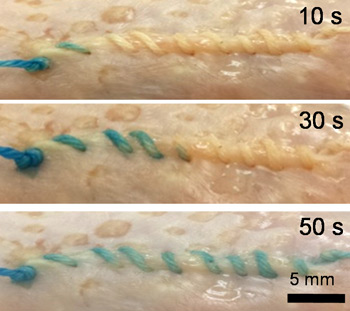

The key to making a suture “smart,” says Sonkusale, is allowing it to conduct electricity. Thread alone won’t normally do that. So, the researchers coated a cotton thread with a conducting material. Some coatings can sense the stretching of tissue. This might indicate swelling. In other cases, the coatings can measure the pH, or acidity, of the tissue they pass through. Changes in pH might indicate an infection is developing. The team sometimes added small sensors in the thread to measure body temperature. They detect when a wound warms, signaling a brewing infection.

As any of these traits change — stretch, temperature or pH — there will be a slight change in the electrical resistance of the suture. That, in turn, will affect how much electrical current the suture can carry, Sonkusale explains. Any changes in resistance can be monitored by a watch-like device. The device sends a tiny electrical current into the suture. It might be worn on the arm or attached to clothing. The device can then send data on what it learns from the wound wirelessly to a nearby smartphone or computer for recording and analysis.

The researchers described their smart sutures online July 18 in Microsystems & Nanoengineering.

The team has developed an interesting way to embed sensors directly into a patient’s skin, says John Rogers. He’s a materials scientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. (A materials scientist can design new materials or analyze existing ones.) Such bio-integrated — or built-into-the-body — electronics can collect data more accurately than wearable devices such as fitness trackers, he notes.

One day, says Sonkusale, smart sutures might be tailored to monitor blood proteins that indicate healing is underway. Or they might monitor blood sugar levels in people with diabetes, he adds.

Doctors might even take advantage of the suture’s capillary action, Sonkusale explains. That’s its ability to wick fluids from one place to another. (This is the principle by which melted wax gets pulled up a candle’s wick, toward its flame.) By using that wicking, sutures could carry drug-laced fluids from outside the body into a wound. Such drugs might fight an infection or otherwise aid a wound to heal more quickly.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.