Smartphones can now bring Ice Age animals back to ‘life’

You can encounter a herd of these accurate 3-D creatures via your smartphone

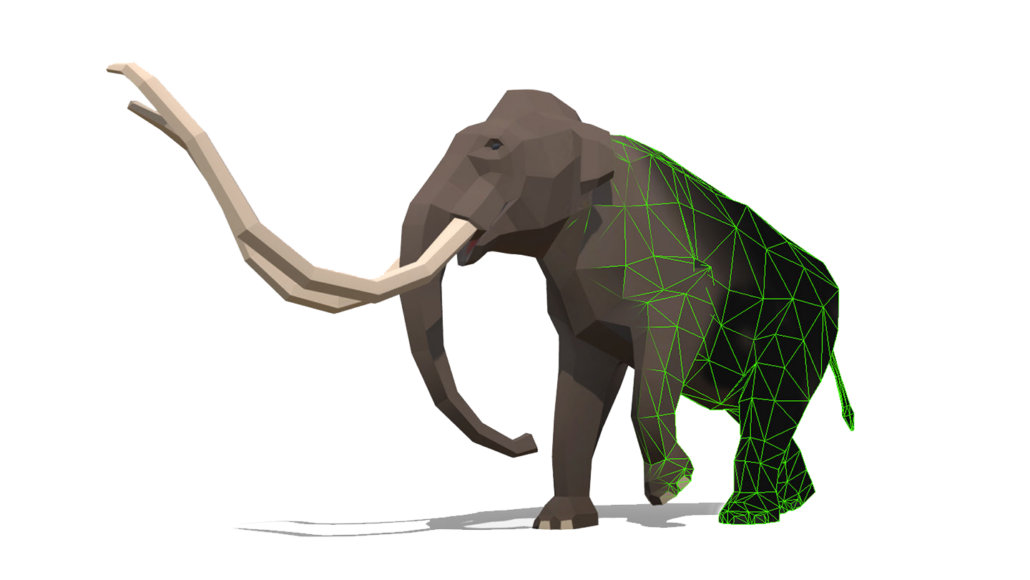

This is a model of a mammoth being developed by the Los Angeles Natural History Museum for use in augmented-reality and virtual-reality immersion experiences.

Courtesy of La Brea Tar Pits

By Laura Allen

Whoa! A saber-toothed cat just sniffed my couch. Yikes, it’s b-b-big! And it roared. Virtually, that is. Scientists have just brought a herd of Ice Age animals back to life — in the virtual world, anyway. You can interact with these creatures safely. Just call them up on a smartphone.

These meet-ups are brought to you through a technology known as augmented reality, or AR. It can superimpose virtual images onto what you see in your environment — be it a classroom, bedroom or soccer field. Or they can come from virtual reality, or VR. Experiencing this is more like entering a 3-D movie, where you are part of the action.

Museums across the United States have been turning to AR and VR in hopes that it will allow people to experience the ancient world in a new and more meaningful way.

Matt Davis works at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, Calif. He and Emily Lindsey, at the museum’s La Brea Tar Pits, wondered if VR and AR might help people learn science concepts better than just reading about them or viewing fossils. They planned to test it using a virtual-reality exhibit on Ice Age animals.

But to do that, the two paleontologists would need scientifically accurate, digital renderings of those now-extinct animals. And they quickly found that there weren’t any. That set them on a new path — to model those prehistoric creatures themselves.

They now describe how they did it in the March Palaeontologia Electronica.

Bringing the past back to life

Without a time machine, we’ll never know exactly what Ice Age animals looked like. Artists often try to show us. But if their images aren’t scientifically accurate, they can misrepresent the ancient world. For instance, many people think velociraptors were large, leathery, dangerous predators. That is, after all, how the 2015 movie Jurassic World portrayed them. In fact, these dinos were actually the size of turkeys and covered in feathers.

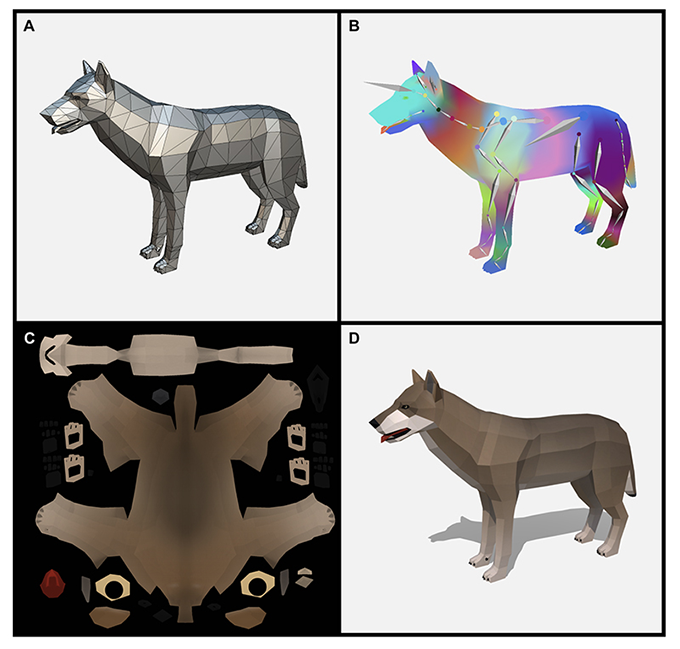

To make their images realistic, the Los Angeles team turned to science. “We used our knowledge of bones, the fossil record and scientific literature to make the most accurate AR models we could,” explains Lindsey. They worked with a company called Polyperfect to make the models. This company creates animated characters for video games. The paleontologists shared detailed instructions on how the animals should look and move. Artists from Polyperfect drew the shape of the model, then animated it. The Los Angeles team reviewed the process along the way.

They also documented the decisions they used to create these new models. For example, they knew from fossils the size of saber-toothed cats. They had to guess, however, on the sound of their roar. Along the way, the team noted which decisions were based on established science and which were based on some educated guess.

Explains Davis, “Anytime people create paleoart, we want them to share the scientific decisions — the research and the artistic decisions they made.” Right now, he says, “Those decisions aren’t usually communicated.”

Mauricio Anton is an independent paleoartist who works with the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid, Spain. He, too, has shared this decision-making process when creating paleoart. Many of those details show up in his scientific papers, books, talks at conferences and on his website. But sharing that process may not always be practical, he adds. It’s time-consuming to write scientific papers, and artists are only paid to deliver a finished product. Unless it is part of their paid work, he suspects, artists may not want to spend the time detailing their methods as the Los Angeles team did.

Yet, Davis argues, “the artistic part is just as important as all the other research.” In fact, he adds, “It’s an important part of how we communicate our findings to the public and other scientists.” In this case, he argues, “Art is a part of [the] science.”

Ground sloth, meet the smartphone

To make their Ice Age animals accessible to most people, the researchers wanted their AR experience to work on smartphones. This meant the models had to be simple. If not, viewing them would use up too much data. The team chose a cartoonish look for their animals. It’s called low poly, short for low-polygon views. (Polygons are the shapes used to represent 3-dimensional details in digital representations.) This simplified the models while still keeping them scientifically accurate.

Afterward, Davis viewed them life-sized in VR for the first time. “I jumped back when I saw the American lion,” he says. “It was so big and scary-looking, compared to me.”

To get the full virtual-reality experience, you’ll have to visit the La Brea Tar Pits. Davis and Lindsey are planning to showcase a virtual Ice Age safari there. You’ll be able to look back in time to see small groups of ancient bison or dire wolves. You can even watch a ground sloth become stuck in tar.

The team still doesn’t yet know how well such virtual displays will improve science learning, but they do know it will be fun to interact with these creatures. Using Snapchat or Instagram, you can too. See a dire wolf approach you. Hear the roar of a saber-toothed cat. Watch a ground sloth rear up in your living room. You can also check out the 3-D models on a computer.

Want more fun? These models are available to purchase and use in your own video games. And for those who prefer pen and paper, you can make your own paleoart. “If you go to a museum and see a skeleton, try to draw what you think the animal would look like in real life,” Davis says. “That’s a great way to start out with science.”